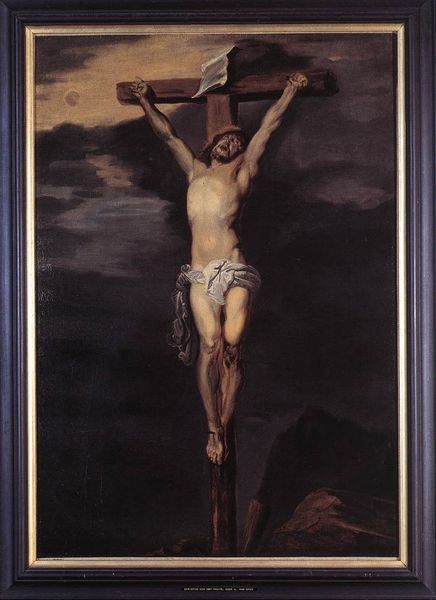

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

history-painting

#

nude

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

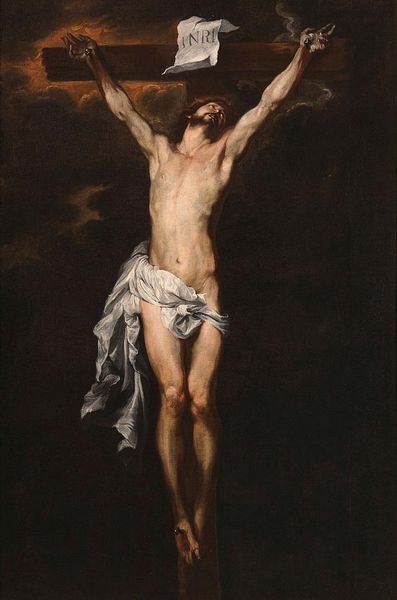

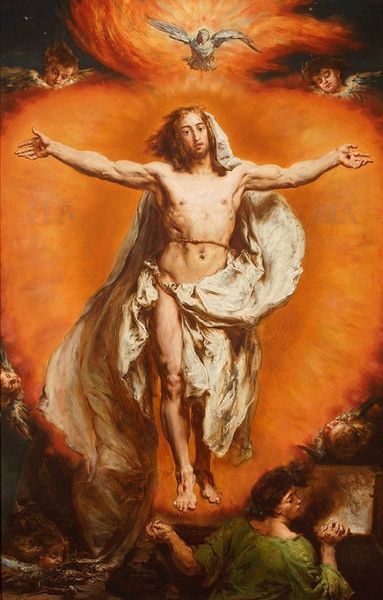

Curator: Let's turn our attention now to Peter Paul Rubens' "Christ on the Cross", a painting likely completed sometime between 1592 and 1633. A monumental work, steeped in the drama of the Baroque. Editor: My initial impression? Overwhelming. The body almost leaps out from the canvas, a visceral study in pain and maybe… exhaustion? The stark palette amplifies the suffering, though it does seem staged, doesn't it? Curator: It is staged, in the way only Baroque drama can be. But consider the social context. Rubens painted for a Counter-Reformation audience. They needed visceral impact, not subtle suggestion. The musculature is not just anatomical display; it's meant to inspire awe, a sense of physical and spiritual endurance. Note, for instance, how the brushstrokes in the body contrast with those that outline the distant buildings in the background. Editor: Right, I notice that almost cartoonish musculature, you're completely right. All those visible efforts he went through for a perfected athletic silhouette, for one thing! But I'm also struck by the artifice – that carefully draped cloth, the almost clean wounds. Where’s the grime and the struggle inherent in such an execution? Even the way his arms look up like that to grasp for light against this dark stormy background… is the figure even nailed to the cross or barely hanging onto it? Curator: Perhaps the cleanliness you mention is about presenting Christ as a divine figure, elevated even in death. Look closely; Rubens uses oil paints to render the skin with a luminosity, hinting at an inner light despite the obvious agony. He isn't trying to capture realism in a documentary sense; rather, to depict Christ’s sacrifice as both human and transcendent. Rubens was clever in his approach. The material's purpose is to translate feelings of exaltation of divinity. Editor: So, Rubens, a master of theatrical suffering, understood his materials as a means to a powerful end. All that suffering made profitable. Not exactly what you'd call "Christ-like," is it? The labor behind all of it, I would say, becomes another form of painful sacrifice by people not even related to the holy figure! Curator: A pointed observation about how meaning and commodity entwine. Editor: It’s that tension, between genuine feeling and calculated display, that fascinates me in Rubens. Curator: Indeed. And "Christ on the Cross" captures it masterfully, a testament to Rubens' skill in manipulating both paint and piety.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.