Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

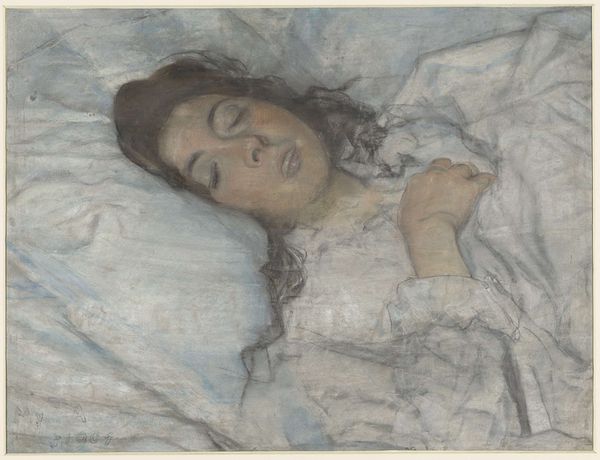

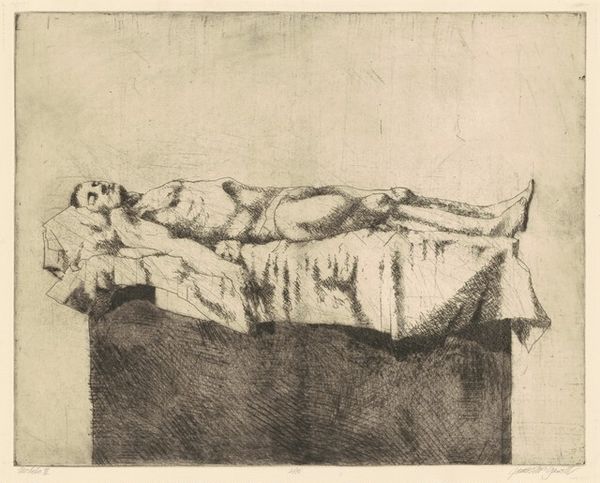

Curator: Looking at this canvas, one immediately senses a mood of profound stillness. The soft colors and the focus on a single, elderly figure contribute to an atmosphere that is both somber and strangely peaceful. Editor: Indeed. We are in front of "Alter Mann auf dem Totenbett," or "Old Man on his Deathbed," painted between 1899 and 1900 by Gustav Klimt. The piece is executed in oil, showing us the artist's handling of light and shadow. Curator: The closed eyes, the gentle curve of the mouth—it's as though the old man is finally released, free from earthly struggles. I'm intrigued by the way Klimt uses soft, almost ethereal brushstrokes to convey the feeling of lightness and release that accompanies death in many cultural traditions. The bed linens appear cloudlike, which almost certainly suggests heavenly ascension, doesn’t it? Editor: Quite possibly, yes. Representations of death were evolving, but frequently death masks or portraits would be commissioned after death. However, Klimt's era witnessed a surge in the romanticization of death, seen as a transition, a doorway—note, for instance, the sleeping posture we see depicted. This symbolism blends into the "memento mori" tradition we see stretching far back. Curator: How do you perceive Klimt positioning this within the visual and social framework of turn-of-the-century Vienna? Editor: Well, his Secessionist cohort sought new aesthetic languages. Think of it: prevailing academic art depicted heroes or allegories, and here is Klimt contemplating mortality plainly, confronting a universal human experience through a unique visual interpretation that feels both raw and deeply intimate. Curator: It prompts me to consider how the public perception of art was challenged in Vienna. Such vulnerable subjects were typically excluded. This piece acts as a social commentary, reflecting changes in art and societal consciousness. The very public act of exhibiting a deathbed scene forced viewers to face their mortality. Editor: I agree completely. The soft rendering does invite contemplation, rather than inciting fear. This visual meditation helps to neutralize death's sting through quiet observation. Curator: Considering how social conventions might have shaped the viewers' perspectives gives this small but emotive painting greater historical and cultural magnitude. Editor: Yes. When seen from an iconographic lens, we uncover complex layers, offering poignant and comforting reflections on life's end.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.