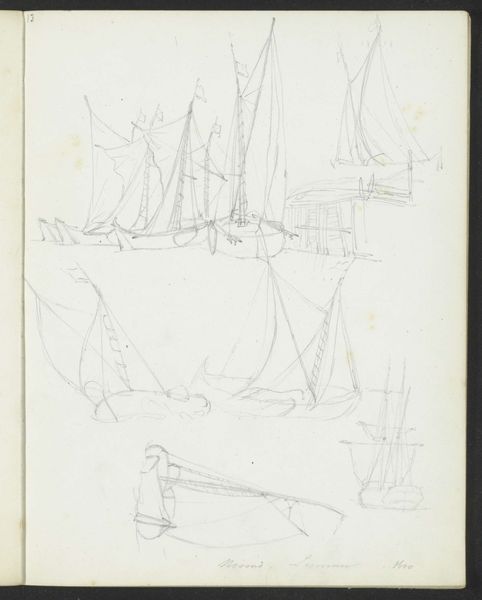

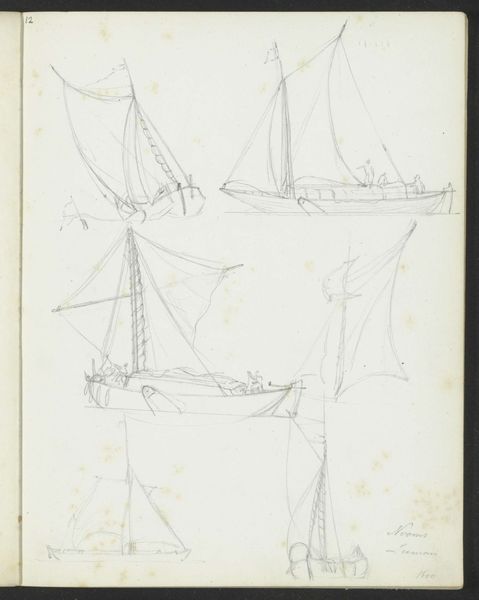

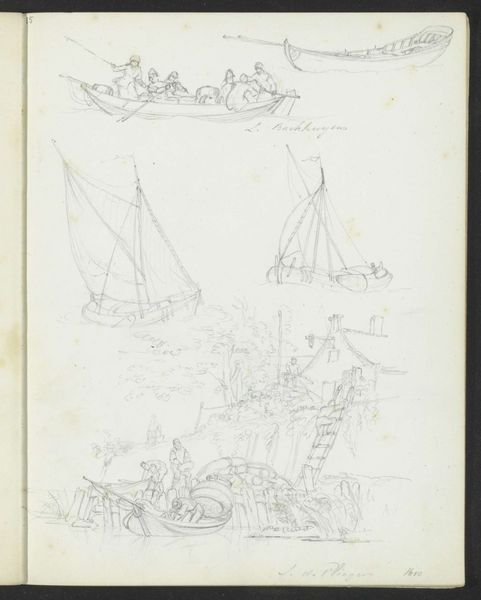

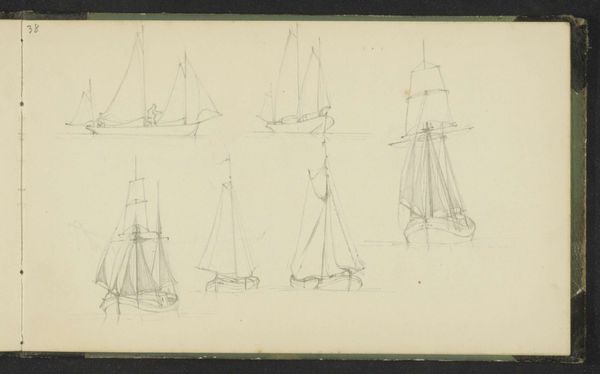

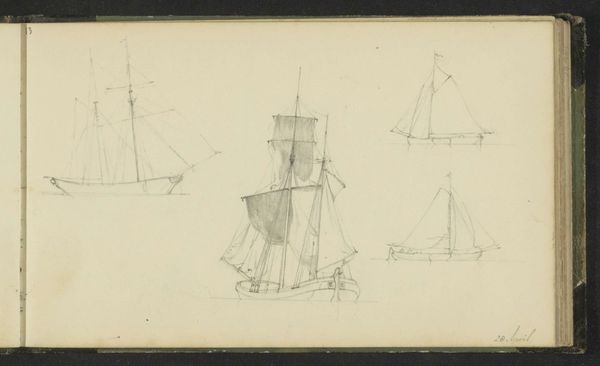

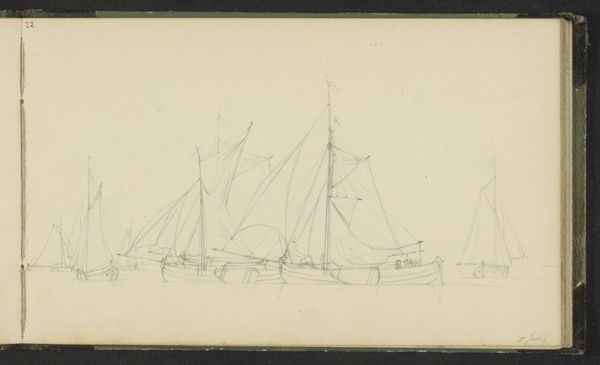

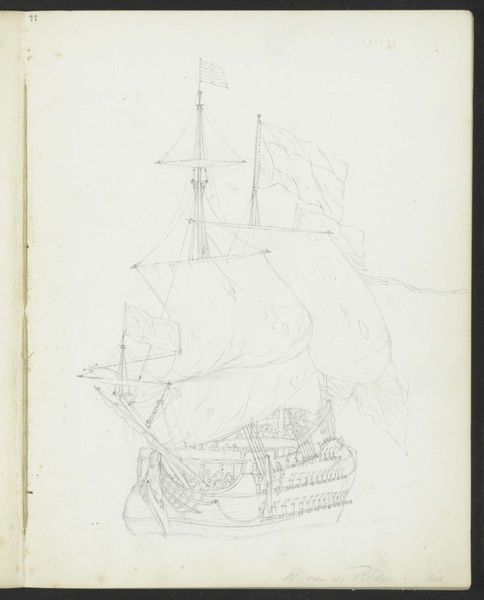

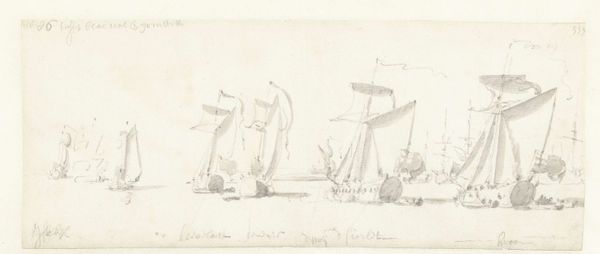

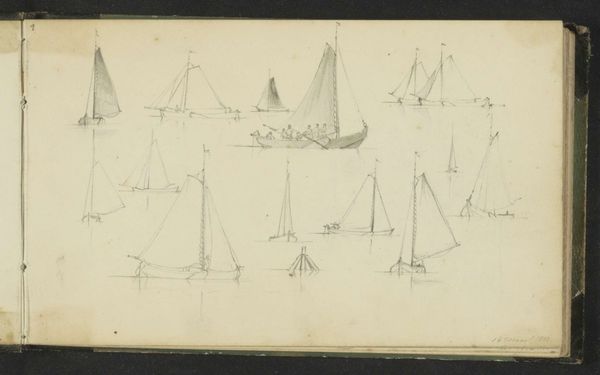

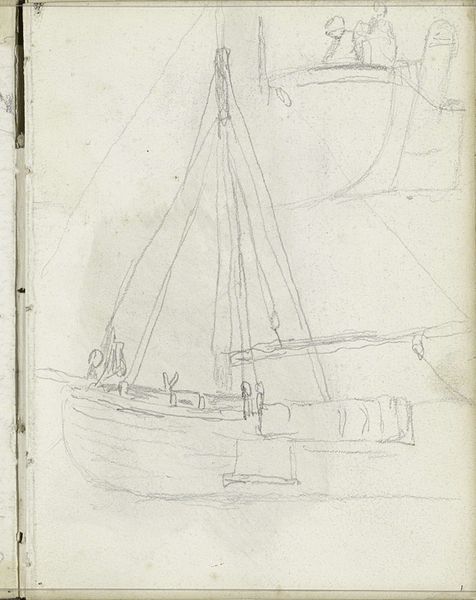

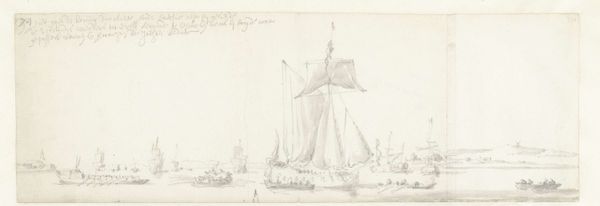

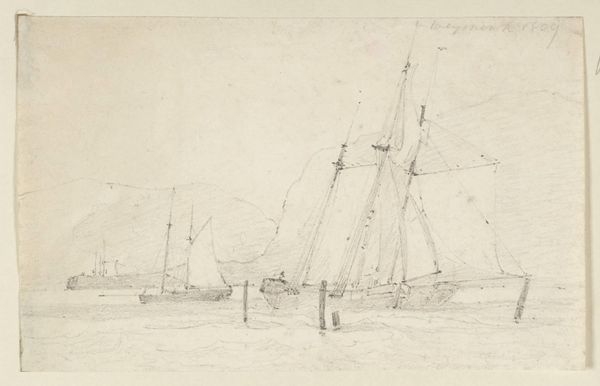

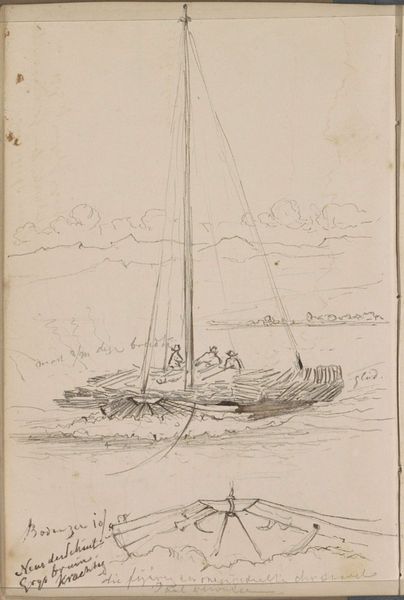

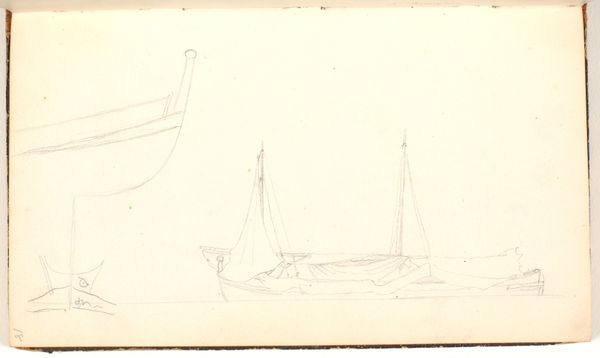

drawing, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

pen sketch

#

landscape

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us, we have a sketch, a page from a sketchbook by Hendrik Abraham Klinkhamer. The piece, aptly titled "Studieblad met zeilboten en -schepen" which translates to "Study Sheet with Sailing Boats and Ships," was created sometime between 1820 and 1872. It’s currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. What's your initial read of this work? Editor: The lightness strikes me immediately. There’s a real economy of line here, creating this almost ethereal fleet. The grey pencil on the creamy paper gives a quiet, pensive feel. Curator: Indeed. It’s important to recognize that maritime scenes were often linked with the power of the Dutch Republic. However, by the 19th century, Romanticism shifts that representation. These boats are less symbols of might, and more like studies of humanity's relationship to nature. There is this inherent theme present where you feel like this isn’t about human triumph over the sea, but more of a humble interaction with its vastness. Editor: I can certainly see that, the delicate pencil strokes almost surrender to the negative space of the paper, hinting at the water's vastness. Thinking purely formally, observe the variety of shapes created simply with changes to the lines themselves. The artist uses this approach in his work here, with a focus on ships’ form and proportion, instead of just the sails. It provides a solid skeletal structure of the ship models. Curator: It invites us to consider labor and trade during this period too. Who manned these ships? What goods did they transport? The romantic era can often sanitize labor so a formal and historical perspective is necessary to understand art as situated, not simply created in a vacuum. We have to address this era as much more complex than the beauty it often presents. Editor: Agreed. Although his intentions are less legible on the page, Klinkhamer’s choice of material—the pencil on paper—suggests an impermanence, maybe something quickly sketched during observation or while traveling. You get the impression that he values the form just as much, if not more, than what they represent. Curator: I am intrigued by that tension. Klinkhamer invites the viewer to meditate not only on his aesthetic composition, but about who it includes and excludes. Editor: The convergence of historical context and pure form creates a nice ambiguity, wouldn’t you agree? Curator: Absolutely. And perhaps that is its quiet power: a space for reflection, and a moment to ask new questions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.