![Soldiers in a Devastated Landscape [recto] by John Singer Sargent](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzU3ZjZiYmM3LTZhMmEtNDRmNy04ZTRiLTNhZmM5ZmYyYjliYS81N2Y2YmJjNy02YTJhLTQ0ZjctOGU0Yi0zYWZjOWZmMmI5YmFfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

pencil

#

modernism

#

realism

Dimensions: sheet: 25.4 × 36.2 cm (10 × 14 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

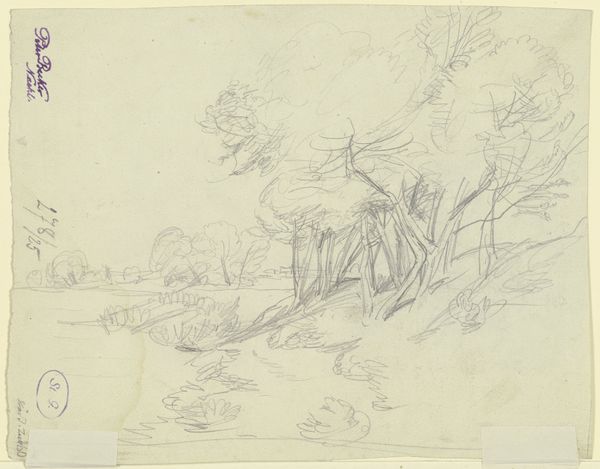

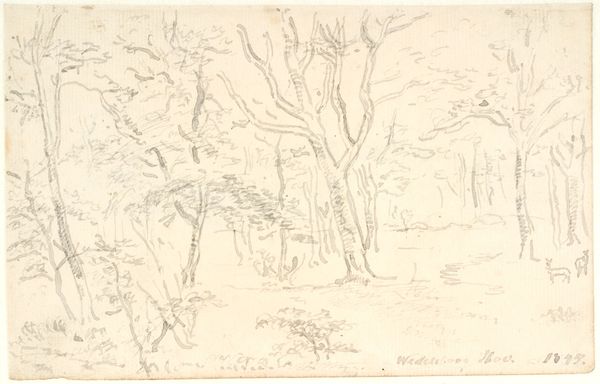

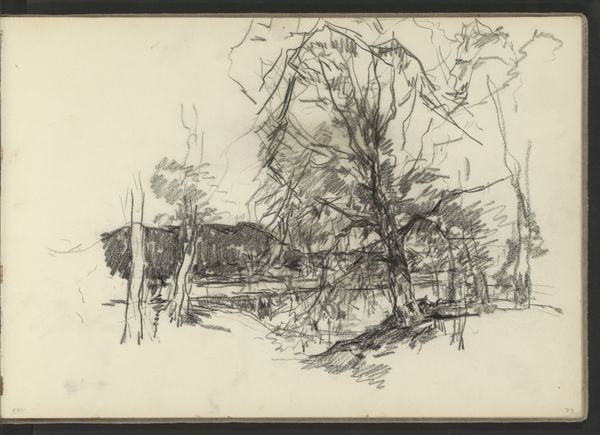

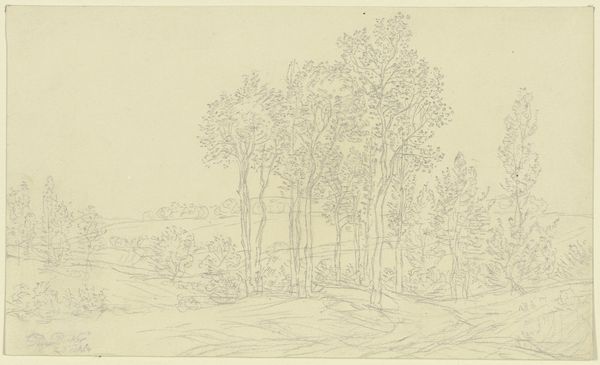

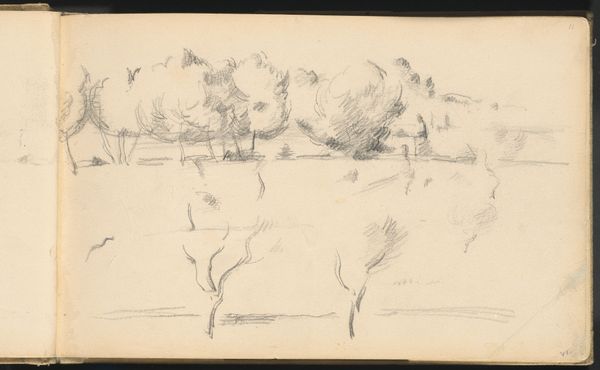

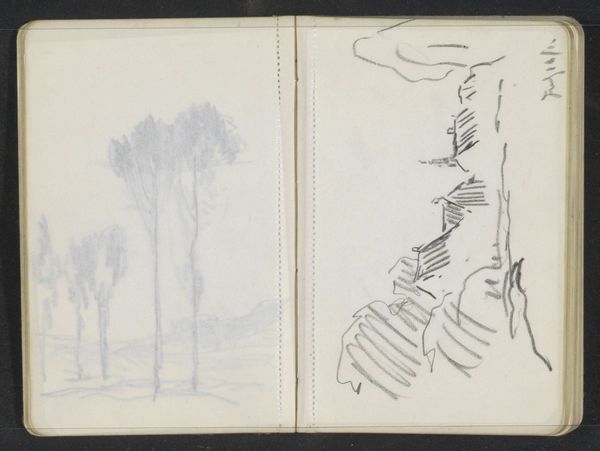

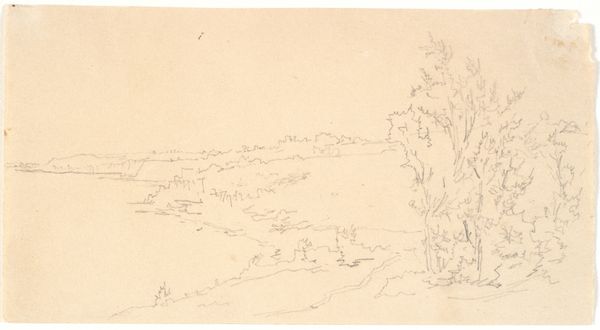

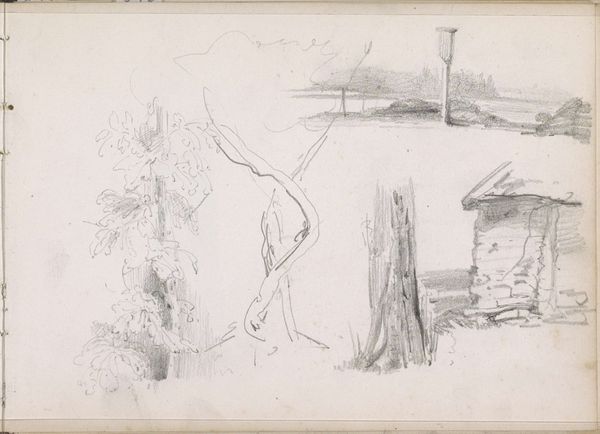

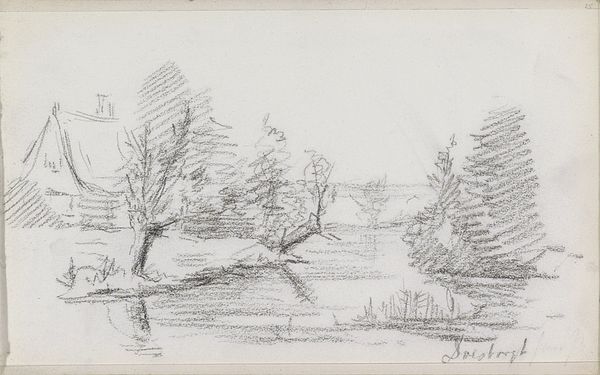

Curator: Let's turn our attention to "Soldiers in a Devastated Landscape [recto]," a pencil drawing created by John Singer Sargent in 1918. Immediately, what comes to mind? Editor: Ghostly. That's the word that springs up. The pale pencil, the fragmented scenes… It's like glimpsing a memory fading. A stark, skeletal echo of war. Curator: Interesting. Considering it was crafted during the final year of World War I, the pallid aesthetic really amplifies the impact that total war had on its landscape, yes. You know, Sargent was originally commissioned as a war artist by the British government. We see two distinct compositions; the upper depicting the destroyed treescape, while the lower half presents the figures—presumably soldiers—amongst artillery. The juxtaposition feels intentional. Editor: Definitely. Almost like comparing what's been taken—those ravaged trees like shattered bones—to those who were actively taking. There is this odd detached feeling given the very active scene that's supposed to be showing warfare. Curator: I agree. In terms of materials, his use of pencil provides this sense of immediacy and fragility—emphasizing the transient nature of war, or how the war reshaped the physical world and impacted those involved. Think about the consumption of raw materials, labor, all in the context of this conflict. Editor: For me, there's also a beauty, if I can call it that, in its restraint. It doesn't scream horror; it whispers loss. A testament to what he witnessed and felt without falling into melodrama. There is something devastatingly intimate about this scene; as if all are one in this landscape. Curator: Sargent was known for his portraits of the wealthy and elite, and one wouldn't immediately place him in this role given this drawing. Perhaps it was his ability to see and depict the realities around him, not just the privileged view that history paints him in. Editor: And to transmute what he felt. It’s almost as though that landscape entered his bones. What remains with me most is the quietude he created out of all of this turmoil. It lingers and invites introspection. Curator: Absolutely. It compels us to remember the cost—both materially and emotionally—of conflict.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.