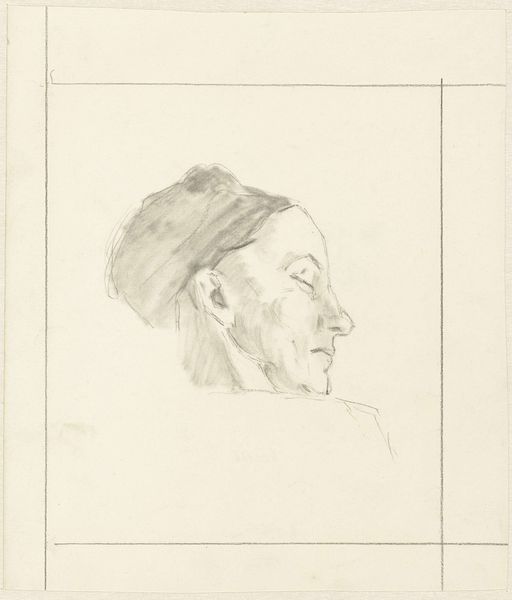

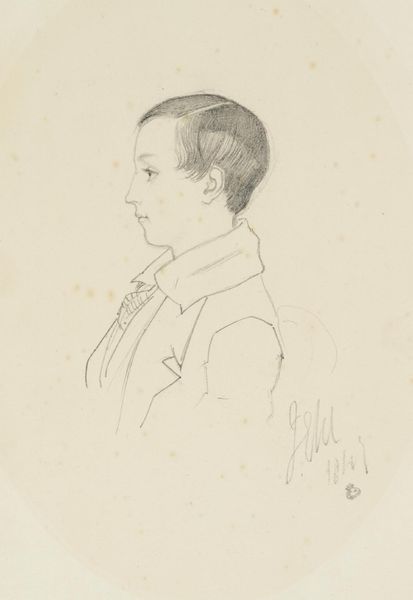

Dimensions: support: 203 x 152 mm

Copyright: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

Editor: This is a pencil sketch of Mrs. Currie by Sir John Everett Millais. It's quite small, and I’m struck by the delicacy of the lines. What can you tell me about the context of portraiture in Millais’s time? Curator: Well, portraiture in Victorian England wasn’t merely about capturing a likeness. It was deeply intertwined with social status and power. Millais, a prominent figure in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, later became a highly sought-after portrait painter. His portraits often reinforced the sitter's position within society. Consider the way Mrs. Currie is presented. Does her attire or posture suggest anything about her place in society? Editor: I suppose the necklace and the elaborate hairstyle suggest a certain level of affluence. But is there more to it than just wealth? Curator: Exactly! Think about the institutional structures that supported this type of art. Who commissioned these portraits, and what did they hope to achieve by doing so? The Royal Academy, for example, played a crucial role in shaping artistic tastes and promoting certain types of imagery that upheld Victorian ideals. The display of wealth through portraiture wasn't simply personal; it was a public declaration. Editor: That’s fascinating. It makes me see how much more there is to portraiture than just capturing someone's face. Curator: Indeed. Examining the social and cultural context helps us understand the complex relationship between art, power, and identity in Victorian England.