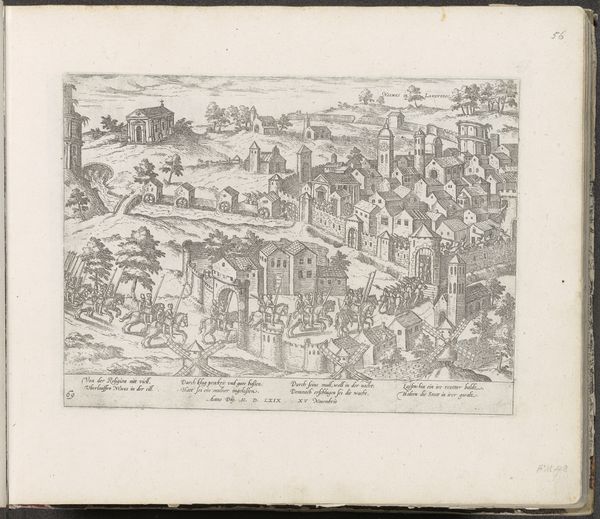

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

drawing

#

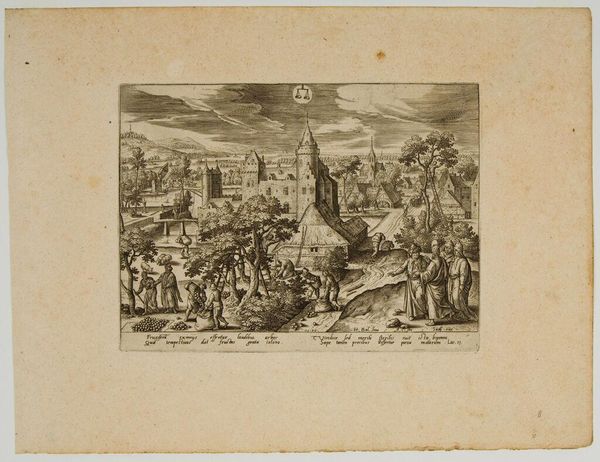

narrative-art

# print

#

landscape

#

paper

#

coloured pencil

#

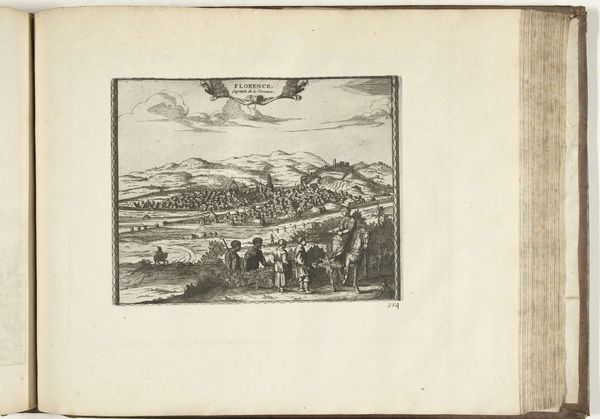

cityscape

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 184 mm, width 242 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

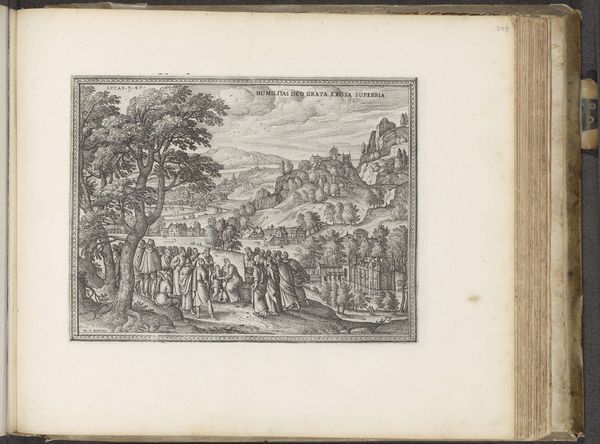

Curator: Here we have Pieter van der Borcht the Elder's "Entry of Christ into Jerusalem," possibly dating from 1582 to 1654. It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The density of detail is striking! There’s so much to unpack. My eye is immediately drawn to the sheer labor involved in creating something so intricate, like weaving a textile almost. Curator: Exactly. Borcht, a master of Northern Renaissance printmaking, would have conceived this as a crucial part of the Protestant visual culture in the Low Countries. The distribution of such imagery played a pivotal role. Editor: It's interesting that you point to Protestantism because you can read the work also as a subtle negotiation of materials, the way he creates tonal variation solely through lines, by cross-hatching, to imply shadow and volume without color. Curator: It served a pedagogical purpose, making biblical scenes accessible to a wider audience and promoting reformist ideas within a fraught political environment. The deliberate placement within a familiar cityscape connects scripture to their everyday lives. Editor: Notice how this isn’t an idealized Jerusalem. It looks very much like a town you'd encounter in the Low Countries at the time, really anchoring this divine narrative in a palpable local materiality. Even Christ's humble transportation by donkey suggests an embrace of material simplicity. Curator: These prints acted almost like visual sermons. In public and private, they reinforced Protestant teachings in spaces often contested by Catholic imagery and ideology. It was visual persuasion operating at scale. Editor: There's almost a blueprint feel in the way the artist's using those graphic tools, inviting viewers to reimagine space. One must consider the economic aspects, since prints like these weren't expensive for those of lower incomes. Curator: It's easy to underestimate the cultural power held by what we might now see as just another "print." Understanding their function then shifts how we value them now, too, as social tools as much as artworks. Editor: I concur; studying the work with its original socio-cultural context gives richer textures that celebrate not only piety but material reality. Curator: Indeed. I find it so captivating how these historical contexts continue to inform how we engage with artworks today, transcending centuries.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.