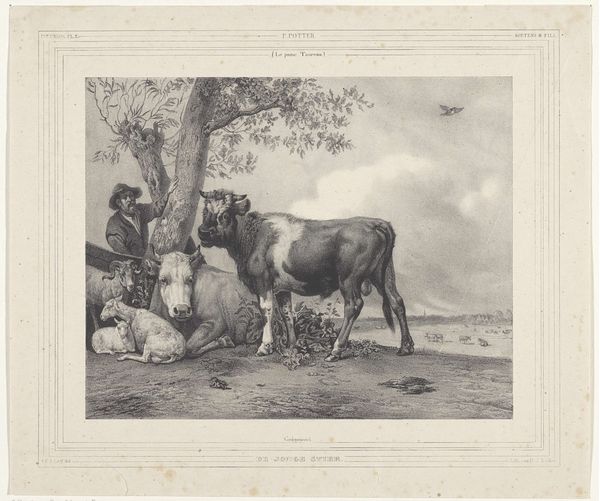

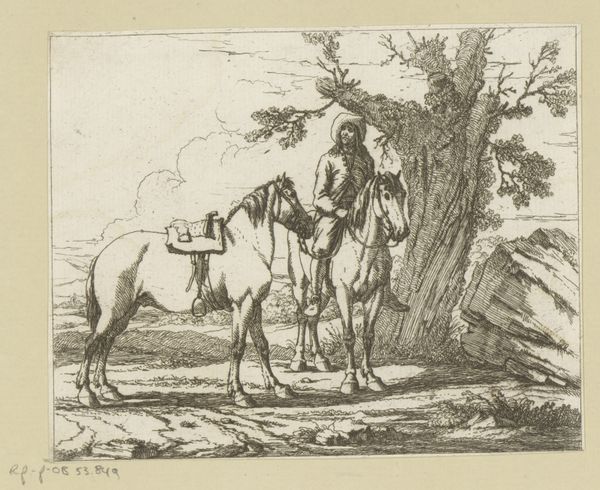

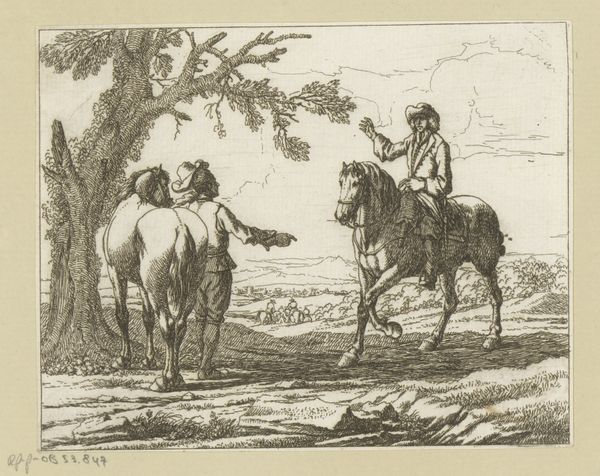

print, engraving

#

neoclassicism

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 239 mm, width 314 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We're looking at "Stier met boer en kudde in een landschap," which translates to "Bull with farmer and herd in a landscape," an engraving by Louis Joseph Masquelier from 1773. What’s your initial reaction? Editor: It feels... pastoral, idyllic even. There's a certain harmony in the arrangement of the figures – the bull, the sheep, the farmer – they all seem to be part of a singular environment that is almost picturesque. There's also an immediate tactile quality. I can imagine the coolness of the paper and the very process of the printing seems to call back to craft. Curator: The composition certainly leans into Neoclassical ideals with its controlled arrangement of figures, reminiscent of a stage tableau. Consider the careful rendering of light and shadow, the anatomical correctness—particularly in the bull. It emphasizes structure. What could this be highlighting? Editor: For me, this focus gestures towards labor as an act of documentation. Masquelier memorializes pastoral life and it feels like something about that memory involves acknowledging how material and place is actively cultivated through human involvement in agrarian activity. It's not a simple idyllic scene. Curator: But the material is very uniform—it is an engraving! What happens when you detach the final image from its social ties and place it purely within the lineage of similar compositional techniques? Editor: The emphasis on the Neoclassical—which emphasizes stability—is complicated by the subject: agrarian practices of cultivating animals and land which would have constantly changed and shifted. Also the means of reproduction matter—the printing medium is itself inherently reproductive—perhaps hinting at the cycle of farming and agricultural means that also constantly produce and change. Curator: Very insightful. Even the contrast—the light against the dark areas in the scene—helps establish this inherent balance of neoclassical forms. We get the stability, we get the temporality and, together, they coalesce into one narrative. Editor: Absolutely. And that's what stays with me: not just the immediate beauty, but this consideration of the way labor is intrinsically connected to social practice. It encourages you to imagine more of that history behind the print.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.