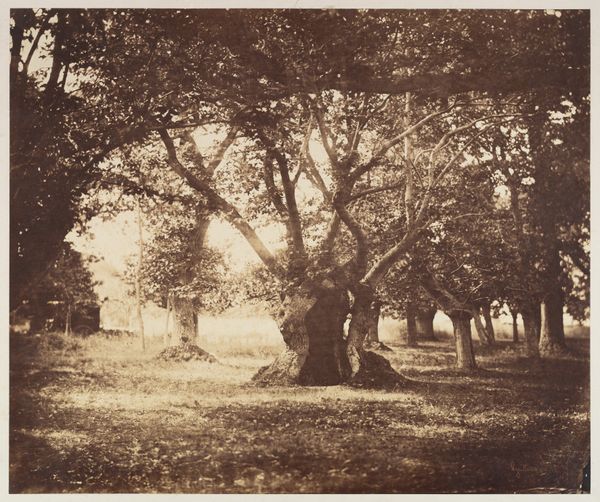

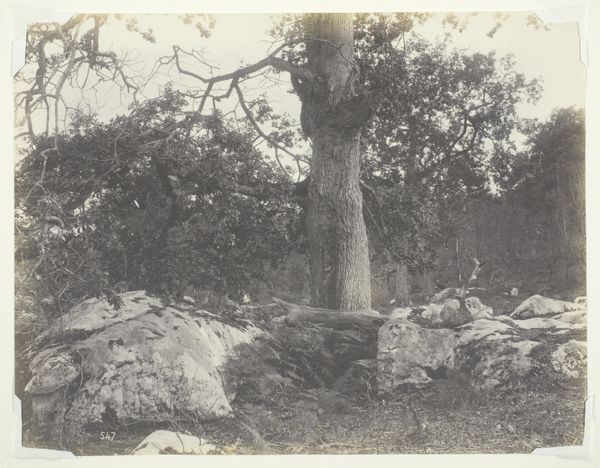

![[The Large Tree at La Verrerie, Romesnil] by Louis-Rémy Robert](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzU3NDZkMWFjLTI4MzgtNDQ1My04YjFiLWY4YTcyNGNmMTA5Ny81NzQ2ZDFhYy0yODM4LTQ0NTMtOGIxYi1mOGE3MjRjZjEwOTdfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

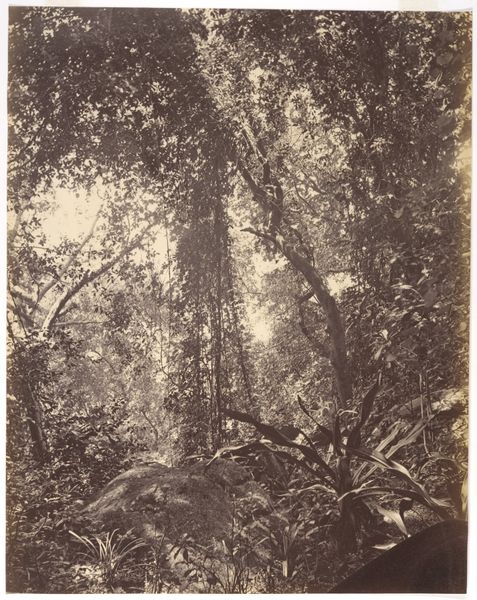

[The Large Tree at La Verrerie, Romesnil] 1850 - 1854

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Image: 10 3/8 × 12 1/2 in. (26.3 × 31.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This daguerreotype, "[The Large Tree at La Verrerie, Romesnil]," by Louis-Rémy Robert, likely taken between 1850 and 1854, feels incredibly still. There's this massive, central tree dominating the composition. How does this image fit into the art and cultural landscape of its time? Curator: That stillness, as you put it, is key. Photography, especially daguerreotypes, held immense power. Think about it – the burgeoning middle class could, for the first time, affordably capture their likeness and surroundings. How do you imagine this impacted portraiture and landscape painting? Editor: It must have challenged their purpose. If photography could so accurately record reality, where did that leave painting? Curator: Precisely. But more than that, consider who had access to these technologies. Early photography was a privileged medium. Images like this one, though seemingly pastoral and benign, reinforce the social standing of the landed gentry and their connection to these romantic landscapes. This wasn't just about representing the tree, it was about claiming a space within the socio-political hierarchy. It’s carefully staged to depict wealth, order, and dominion. Notice the calculated, yet seemingly untouched view and tell me, what does it tell you about photographic choices? Editor: It's interesting how something seemingly objective like photography could still carry such heavy social baggage. The tree now feels like a symbol, a pillar of societal strength or ownership almost. I'll definitely look at 19th-century photographs with a more critical eye now, seeing beyond just the surface representation. Curator: Exactly, by examining these historical forces, you realize photography is a culturally biased technology! The more information we gather on photographic equipment and production, the better we get to grasp society as a whole.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.