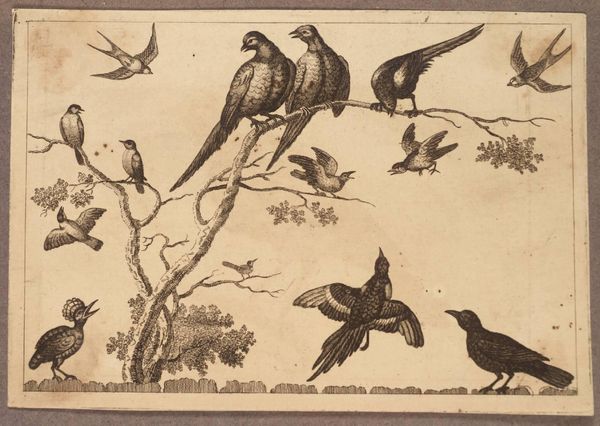

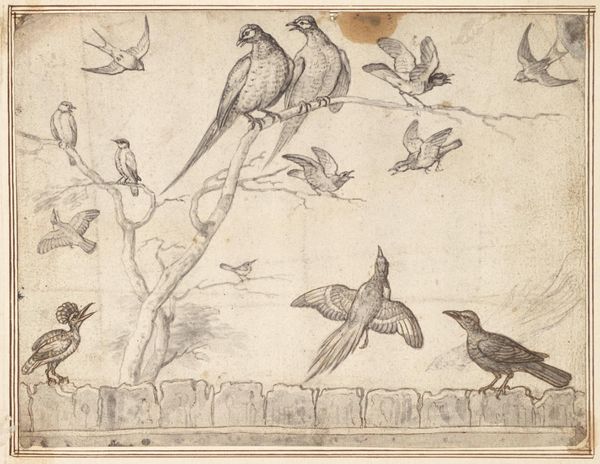

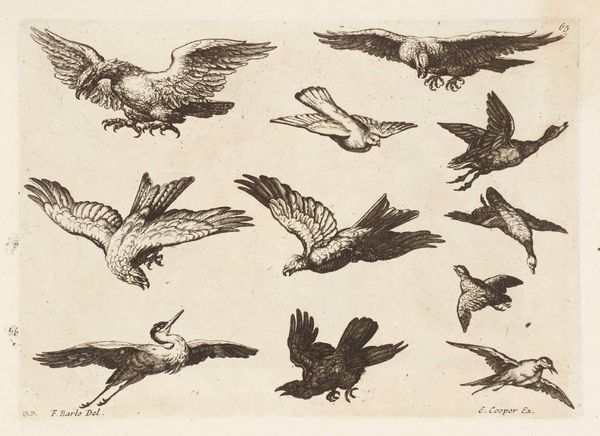

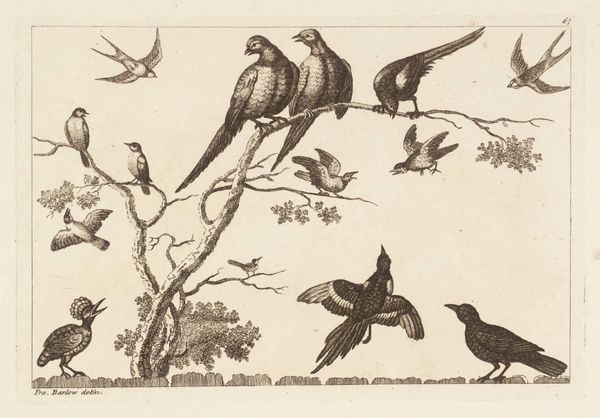

drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

#

animal

# print

#

etching

#

bird

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 59 mm, width 100 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome to the Rijksmuseum. We are standing before a print entitled "Allerlei soorten vogels," dating from approximately 1560 to 1620. It’s an etching, engraving, and drawing all in one. Editor: It feels like a page torn from a bestiary, but less interested in myth and more in observation. What strikes me is the sheer variety presented – it’s like a catalogue, but imbued with a sense of movement, almost chaos. Curator: Exactly. Produced in the Northern Renaissance, likely intended for a collector's album or as a model for other artists. Prints like these facilitated the spread of knowledge and artistic ideas at the time. The depiction of fauna was gaining momentum in representing global geographical understanding and curiosity about the natural world. Editor: You know, looking at them, I think of the colonial gaze – of taking, naming, cataloging. Do you think these representations were a way to control and categorize the unfamiliar, the foreign? The drawing and etching seem so matter of fact. It almost makes it sterile. Curator: That's a sharp point. Consider the socio-political atmosphere during the Renaissance. Exploration and trade expanded drastically and such imagery not only provided visual documentation but, implicitly or explicitly, it reinforced the perception of dominance and the 'civilizing' mission of European societies. The scientific study of ornithology became formalized only later. Editor: And yet, within this act of supposed scientific neutrality, there's the inescapable imprint of a worldview, right? A way of framing and understanding the world, positioning the observer as inherently superior or, at least, centrally important. There is a power relationship. Curator: Indeed, and that tension – between objective representation and embedded ideologies – is, to my mind, one of the fascinating aspects of such pieces. It holds within itself not only an aesthetic and documentary value, but becomes a primary resource to dissect and comprehend a time period. Editor: Precisely. What do you make of how they’re all squashed together like that? In contrast to many natural history drawings, they lack individual environments. Curator: That emphasizes their function as specimens to be compared, and possibly their presence side by side in a menagerie. Now look at how that focus changes our reception… Editor: Absolutely. This image makes me think about our impact on species extinction today, which, I believe, adds another layer to viewing this early modern study. What do you take away from it? Curator: I'm left contemplating how images participate in world-making. They don't simply reflect what exists, they help to shape what can be imagined and, therefore, what actions become possible. Thanks for providing an eye-opening, nuanced analysis. Editor: Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.