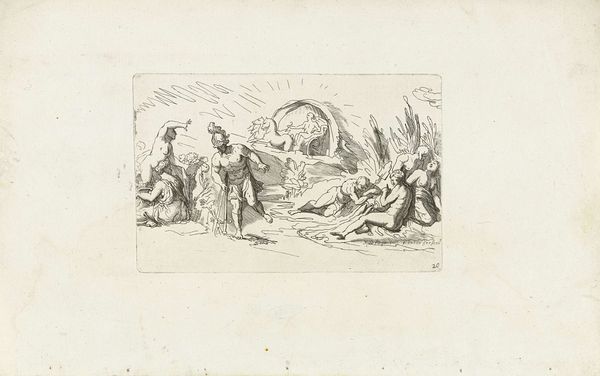

print, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 130 mm, width 165 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome! Before us hangs Frederick Bloemaert's "De Maand December," an engraving dating to after 1635, currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The scene feels desolate. There's a distinct chill in the air, evoked through those barren trees and heavy clouds. It presents such an intimate portrait of rustic life in December, devoid of typical winter holiday celebration. Curator: Bloemaert, although perhaps best known as an etcher, demonstrates here an astute grasp of engraving. The detail achieved—especially in rendering the varied textures of clothing and the nuances of the landscape—speaks to a deeply skilled process. How the lines create depth. Editor: That man precariously perched in the bare tree seems to symbolize the year's end—stripped bare, waiting. The group tending to the ground may signify enduring life sustaining labor and resilience in bleak midwinter. Do you see a connection? Curator: Absolutely. Think about what’s absent: colour. Everything hinges on line and tone, drawing our attention to the physicality of labor and its products. These are ordinary people in the throes of ordinary tasks. It encourages thought around the cyclical patterns that constitute labor and its vital role at the center of our social structure. Editor: But that cyclical aspect suggests hope too, no? The work continues, anticipating the coming spring. There's an implied promise in this dedication, this ritualized task-execution. The dark weather amplifies themes of endurance and silent resolution; a pre-industrial worldview permeates the image. Curator: Well, one could read into the image of those figures drawing material up out of the ground to be symbolic of both agricultural process, sure, but also the ways that materiality is so frequently transformed and consumed for industrial and social reproduction, even then. Editor: So, what lasting significance might Bloemaert seek to impress upon a seventeenth century public by focusing on working people against this cold background? I suspect there might be a political statement latent within this piece concerning shared social duty in December time. Curator: That’s plausible. For me, the enduring resonance of “December” lies in its tangible and exacting demonstration of skill and materiality, its connection to the ordinary but nonetheless critical labour of everyday life. Editor: Yes, there's something universal and very human rendered in this humble little image. The figures are working, of course, to meet life’s material requirements, but Bloemaert's sensitivity endows it with greater cultural significance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.