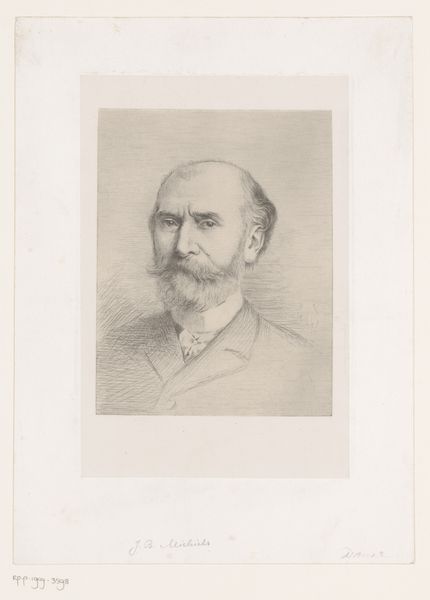

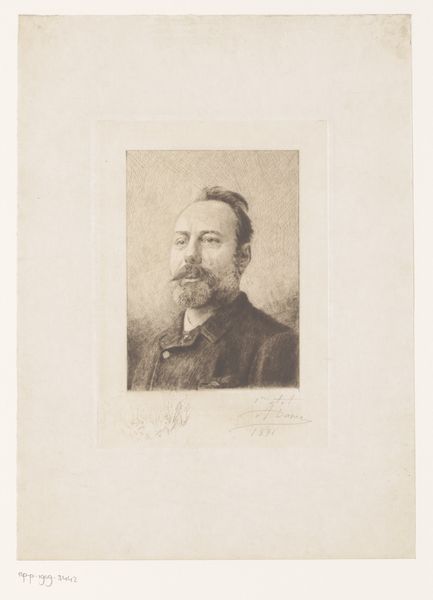

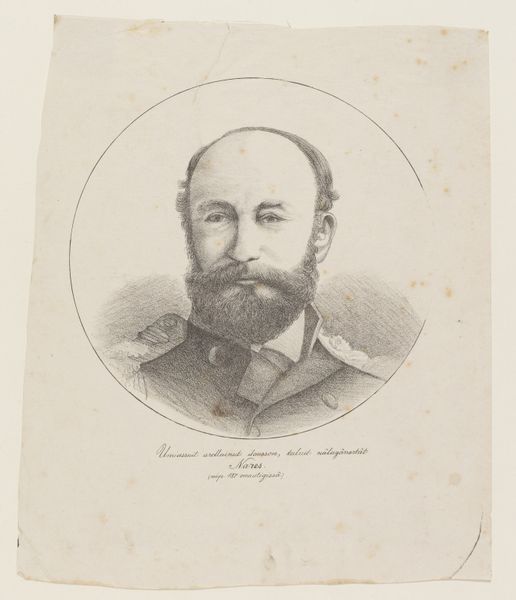

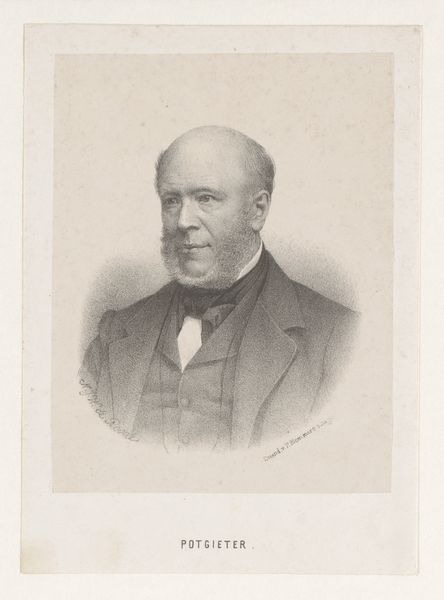

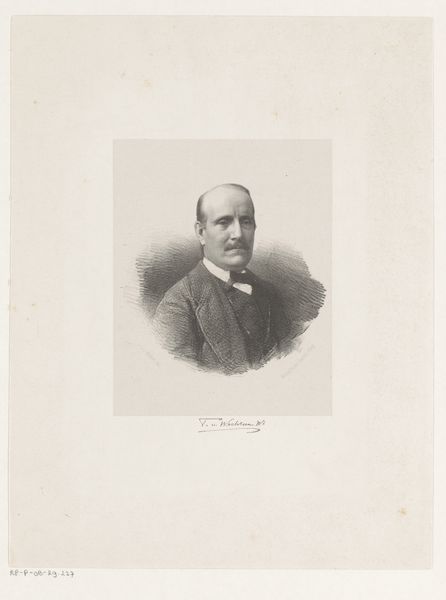

drawing, pencil

#

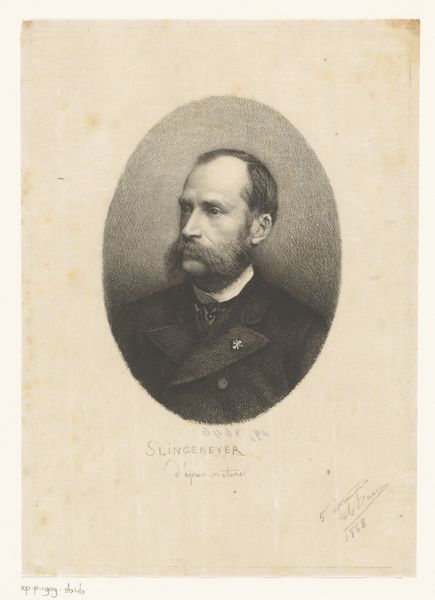

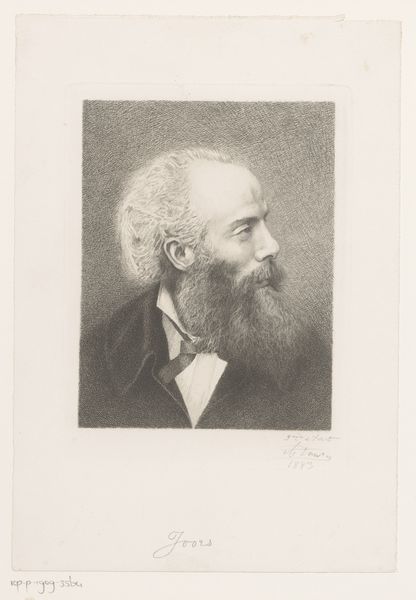

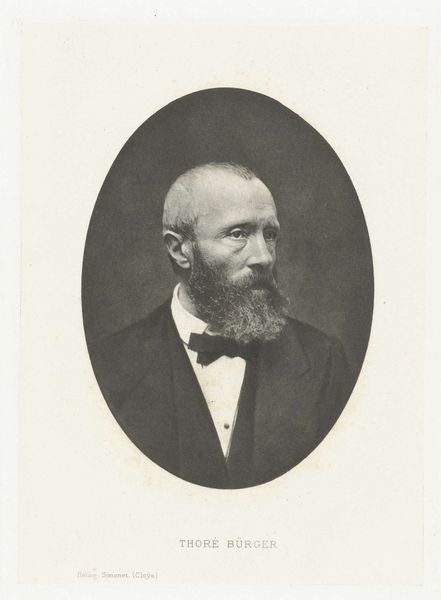

portrait

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

#

charcoal drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 271 mm, width 181 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

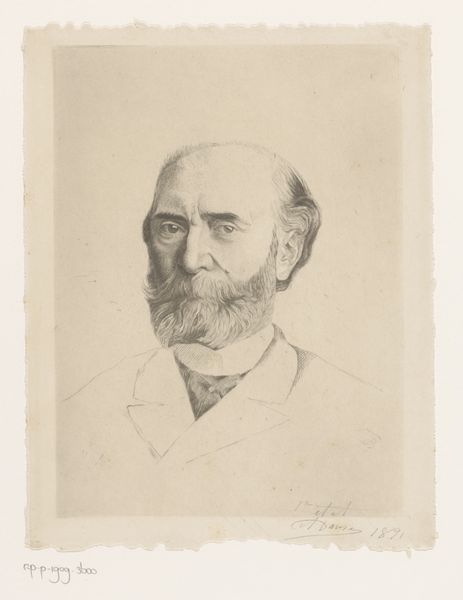

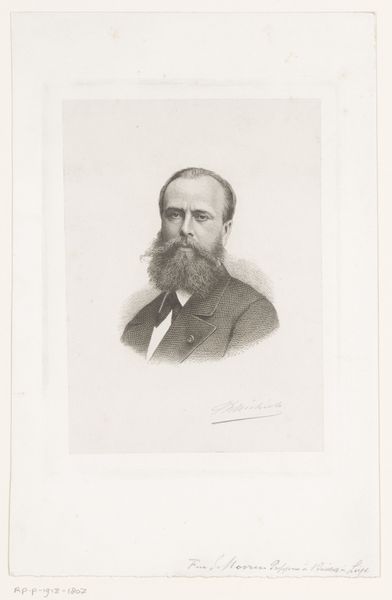

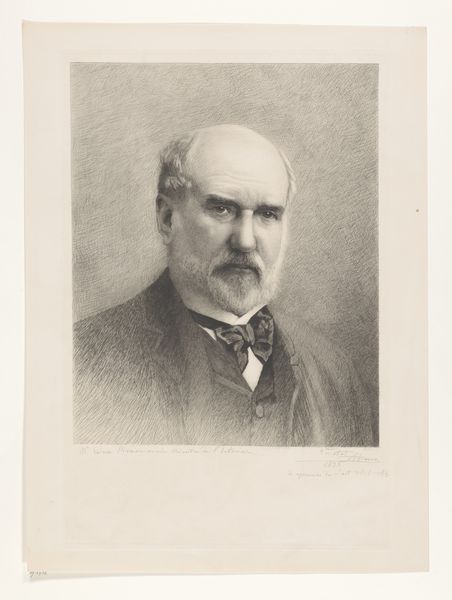

Editor: Here we have Auguste Danse's "Portret van Jean Baptiste Michiels" from 1891, a pencil and charcoal drawing. I'm struck by the intense gaze of the subject and how formal the whole piece feels. What do you make of it? Curator: It’s interesting to consider this portrait in the context of late 19th-century Belgium. Think about the rise of photography and its impact on portraiture. Artists increasingly sought to offer something more than a simple likeness. Do you notice how Danse uses light and shadow? Editor: Yes, there’s a very soft, almost diffused quality to the light. It's not starkly realistic. Curator: Exactly. That artistic choice elevates the portrait beyond mere representation. We need to think about the sitter, too. A man of evident status, captured at a moment of Belgian history defined by social stratification. Portraits like these were often tools for reinforcing and communicating that social hierarchy. Do you get a sense of that being performed here? Editor: Definitely. There's a weight of importance in his expression and posture. It feels like a conscious display. But it is just a drawing; what made that a suitable medium? Curator: The choice of drawing is deliberate. It emphasizes the skill of the artist, as this was pre-photography when such works still enjoyed high demand from the bourgeois, whilst nodding to the wider artistic landscape. Editor: That makes sense. I hadn't thought about the performative aspect of status intertwined with artistic trends. Curator: Indeed. And viewing it today, we can analyse not only the sitter, but the image's contribution to constructing a visual language of power in the 19th century. Editor: I'm now considering the social function of this type of art. Thank you for pointing that out. Curator: My pleasure. It's fascinating to see how these older artworks speak to us about enduring themes in culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.