photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

19th century

#

realism

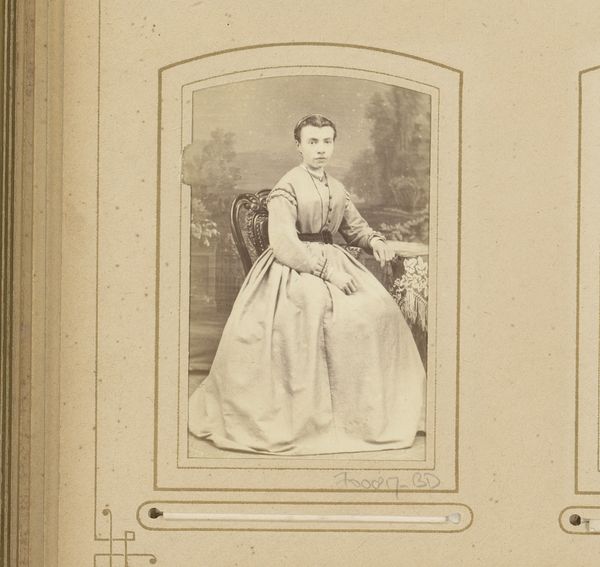

Dimensions: height 107 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

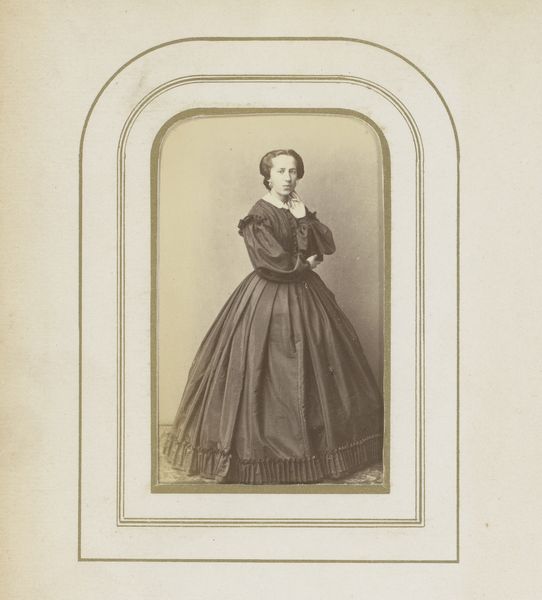

Editor: Here we have H. Ostis’s “Portret van Signe Hebba,” a photographic portrait from between 1864 and 1866. I find it captivating how the subdued tones give it such a strong historical weight. How do you read this work? Curator: Well, let’s consider photography in this period. It’s a relatively new technology, transforming portraiture and representation. Who had access to it? What were the labor practices involved in producing these images, from creating the photographic plates to the development process itself? Editor: That's a great point. It wasn't as simple as a quick snapshot like today! What did it mean to have your photograph taken then? Curator: Exactly! It was a marker of social standing, tied to the resources and capital needed for both the sitting and the production of the image itself. Notice her dress: consider the cost and labor involved in its construction – the fabric, the pattern, the tailoring. These details communicate a certain level of affluence and social positioning. It reflects consumption as a cultural practice. What choices were being made? Editor: I never considered it that way! So, the photo is not just a representation but also evidence of societal hierarchies? Curator: Precisely. It invites us to consider the complex relationship between the subject, the photographer, and the socio-economic forces at play. Signe Hebba isn't just an individual, but a product of and participant in a system of production and consumption. Editor: I'm seeing the photograph in an entirely different light now. It's like the image itself becomes a historical artifact revealing production. Curator: That's it. We’re less interested in the sitter as an individual but in her material existence and the photograph as a form of 19th-century consumer culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.