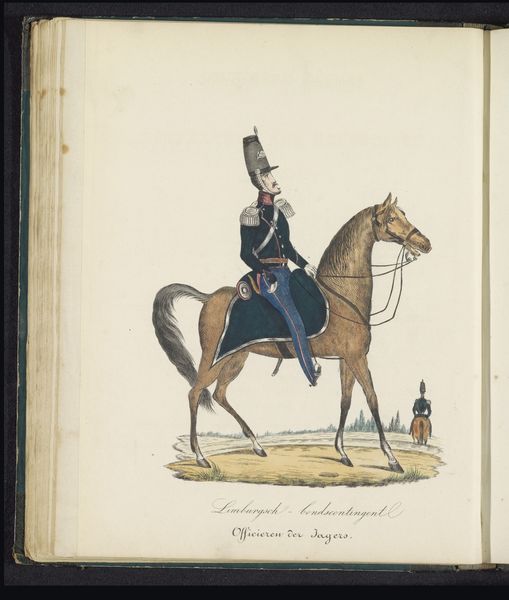

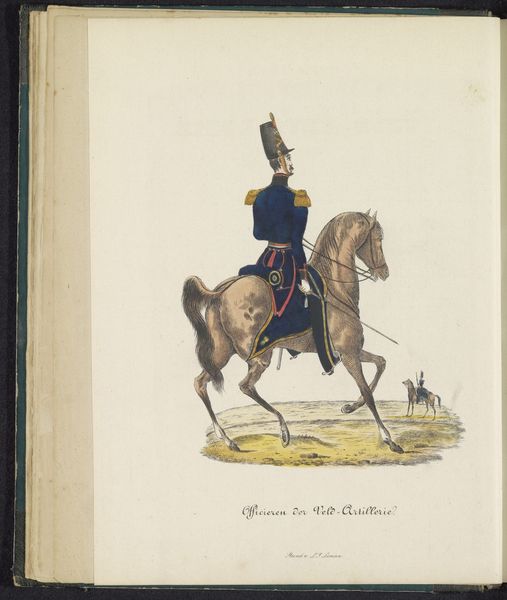

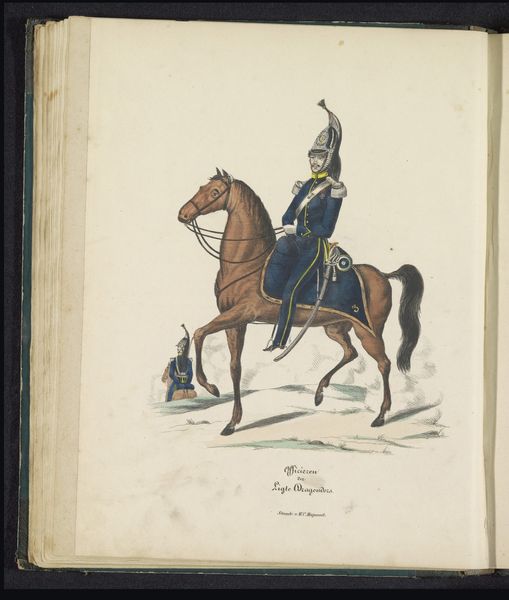

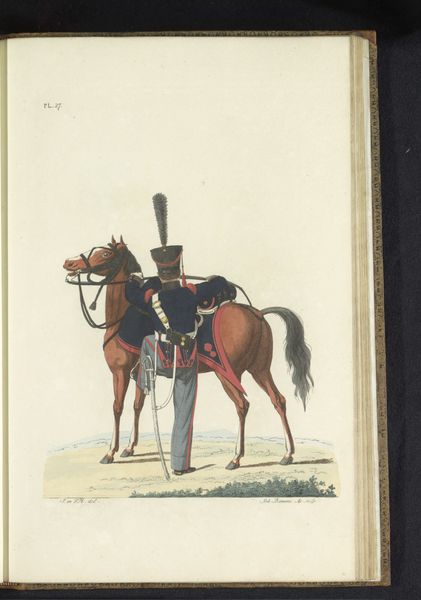

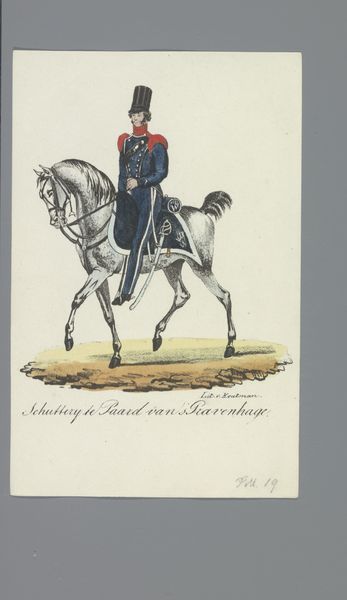

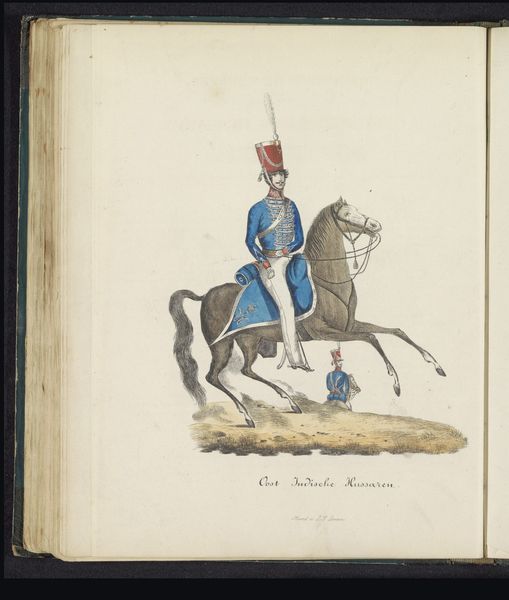

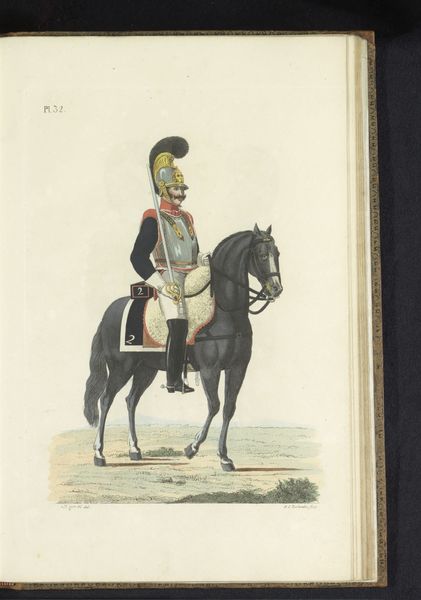

coloured-pencil, watercolor

#

portrait

#

coloured-pencil

#

landscape

#

caricature

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

Dimensions: height 300 mm, width 205 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we see “Dragonder, te paard, in groote tenue” created in 1823 by Joannes Bemme, residing here at the Rijksmuseum. It's made with coloured pencil and watercolor. What's your immediate take? Editor: Striking, yet unsettling. There's a certain confidence conveyed by the rider's upright posture and raised saber, but also a hint of fragility, especially in the delicate rendering of the horse. The work is evocative of a time where warfare held romantic ideals. Curator: I'm immediately drawn to the techniques Bemme employs. The application of watercolor combined with coloured pencil offers a textural quality that's quite intriguing. The artist highlights the production of military identity through manufactured and tailored garments. Editor: I think looking at it from the context of post-Napoleonic Europe really deepens our understanding of the artwork. Consider the social and political upheavals. This image offers an idealised and heroic representation of a soldier. What narratives are consciously included and what aspects of conflict are omitted? Curator: Precisely! Bemme’s artistry extends beyond mere documentation. He subtly hints at the industrial mechanisms supporting military endeavors—a kind of precursor to the mechanization of conflict. We see the intersection between artistry and production. The use of colour further underscores this, almost creating a fabricated spectacle of military life. Editor: This image is interesting as a representation of power and status in the Netherlands in 1823. How does the artist reinforce gender norms or explore national identity? Who does it leave out of the story, considering only some had access to power and privilege? Curator: These watercolour and colored pencil techniques used here emphasize the process involved in creating a piece destined to portray a heroic symbol, and it blurs our notions of artistic craft, production and its engagement in social issues. Editor: And in this dialogue we see both perspectives! We consider it formally in its time, but also examine its enduring relevance within contemporary critical conversations about identity, conflict, and representation. Curator: Yes, precisely. Seeing the artwork within those critical frames opens new understandings. Editor: Indeed, It provokes thought about how narratives of nationhood and power are crafted and reinforced through visual culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.