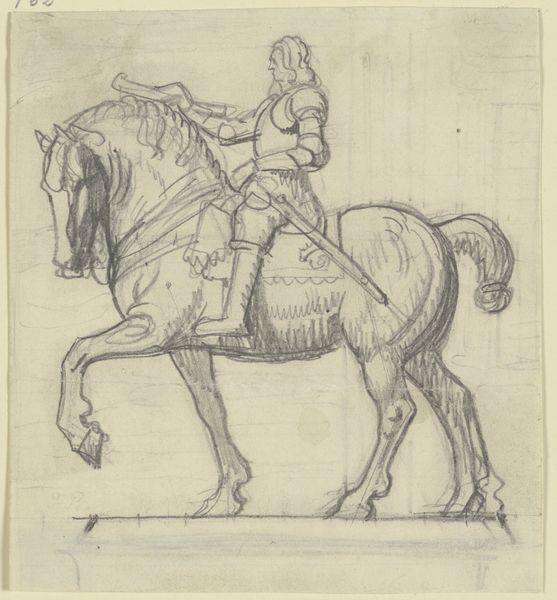

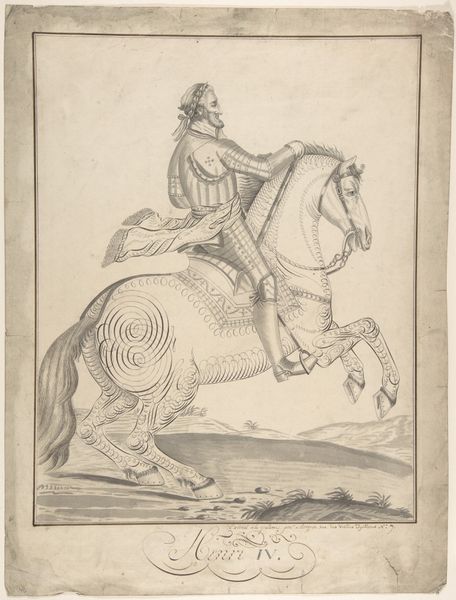

Man on Horseback, Study of a Man's Head (recto); Head of a Young Woman (verso) 1483 - 1548

0:00

0:00

drawing, ink, pencil, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

coloured pencil

#

coffee painting

#

underpainting

#

pencil

#

charcoal

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: 7-9/16 x 7-15/16 in. (19.2 x 20.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This drawing, "Man on Horseback, Study of a Man's Head," was created by Marcello Fogolino sometime between 1483 and 1548. It’s currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Looking at it, I'm struck by its quiet confidence. Editor: My initial impression is less confident, more contemplative, perhaps even melancholy. The figure and his mount seem to be in a world of their own, the lines soft, gestures still, mood reflective, despite the strength implied by the horse. Curator: The horse in classical antiquity and the Renaissance carried connotations of status, nobility, control. Given this symbolic weight, and considering the period, it might signal the power dynamics in society, reflecting a stratified social order. Editor: Precisely, and this reading offers avenues for deeper understanding. The sitter, bearing similarity with an apostle, a saint or even Christ, appears burdened in some respect; the horse thus transforms into the heavy mantle of institutional or ordained authority. Curator: Considering the "Head of a Young Woman" on the verso, it's easy to see it as part of a dialectical game with dualities: power and humility, the masculine and the feminine. Fogolino sets up this symbolic mirroring within the piece itself. It reminds me of similar iconographic practices within illuminated manuscripts from that time. Editor: I wonder about that "recto-verso" opposition, though. It tempts one to essentialize womanhood as automatically humble, as merely the background for supposedly 'important' concerns. Doesn't such division, subtly encoded in the presentation, reflect and then reinforce historical oppression? Curator: It’s a fair point. Perhaps Fogolino was indeed complicit in such projections, which were undoubtedly prominent in his sociohistorical context. Yet, it's still important to see how his personal visual vocabulary negotiated these power dynamics, perhaps unwittingly revealing his internal conflicts or uncertainties. Editor: Exactly! What seems ‘natural’ or given is so often a potent staging ground for unspoken tensions. And studying the iconography, as you mentioned, reveals how those dynamics circulate. Curator: It really enriches how we engage with art, making these older works startlingly relevant. Editor: Agreed; thinking critically and considering varied perspectives gives the drawing fresh relevance even now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.