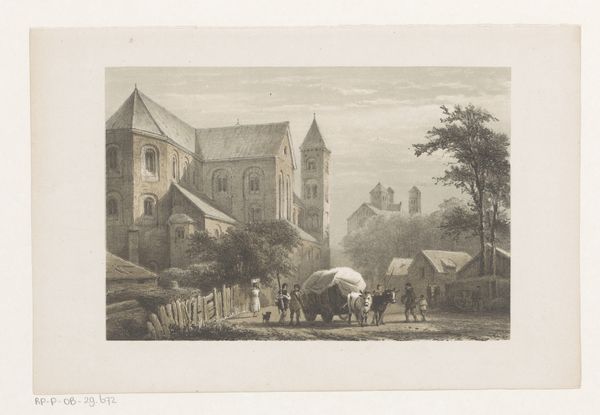

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This drawing, created in 1856 by Karl Friedrich Harveng, is titled "Vor den Toren von Bacharach" or "Before the Gates of Bacharach". The work on paper uses pencil and etching. What strikes you most upon seeing it? Editor: The moodiness. There’s a hazy quality to the light, but the presence of the children adds a layer of darkness for me, a sense of precariousness. Curator: Ah, the symbolic weight of children is significant, often reflecting themes of innocence, vulnerability, and the future. In 19th-century art, such images also touched upon social anxieties regarding poverty, education, and the disruption of traditional ways of life due to industrialization. Notice the details around them too. Editor: It's a village on the move, really. There's something both nostalgic and unsettled in this vision of community, maybe even about cultural heritage itself—considering the castle-like building in the backdrop feels grandiose, almost melancholic as it looms over them. There’s a lot happening, but little joy. Curator: The presence of architecture against nature and figures provides a lens to study history’s layering of meanings onto place. A gateway traditionally marked a point of transition, separation, or even protection. In this work, figures find themselves in relation to its function and that of Bacharach itself. How do you feel that context connects with your reading? Editor: Seeing the architecture as the cultural institution that is trying to contain them offers new layers to what I felt was precarious. What kind of gate are we talking about when the community looks vulnerable as it enters a space. Curator: Interesting that you used "vulnerable". Indeed, Harveng may be offering a commentary on the Romanticism, questioning its ideals by acknowledging the darker side of the time and place he depicted. This image might not be a straightforward celebration but instead invites deeper questioning of a world undergoing change. Editor: Seeing this has made me question what exactly I’m looking at in a landscape or portrait. In what ways does it carry these collective and personal imprints. Curator: Absolutely. And reflecting on Harveng’s composition today can perhaps prompt us to more deeply question inherited iconography.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.