print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

form

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 140 mm, width 195 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

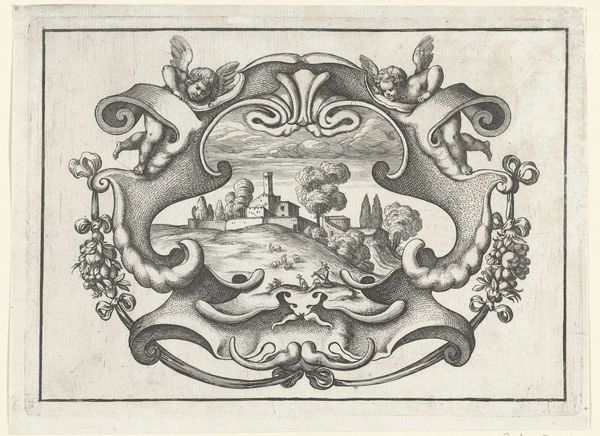

Editor: We're looking at "Cartouche met monsterhoofden en twee guirlandes" – a 1634 engraving by Daniel Rabel. The detail is astonishing! There's a central landscape scene, but it's surrounded by these elaborate, almost grotesque decorations. How would you interpret this interplay of imagery? Curator: It’s interesting that you mention the grotesque element. These “monster heads” weren't intended to be purely frightening. In the context of 17th-century printmaking, particularly with the rise of the decorative baroque style, elements of the bizarre were used to convey wealth, taste, and erudition. It signifies a patron with refined and perhaps unconventional sensibilities. This engraving, and others like it, circulated among artists and craftspeople. Editor: So, it's like a status symbol through artistic consumption? Curator: Precisely! The dissemination of images via prints directly impacted design across different media. We see this visual language echoed in furniture, architecture and garden design from this time. Consider how access to such images might also reinforce or perhaps challenge class structures as visual literacy grew. Editor: That's fascinating. Did the landscape in the center have a role to play as well? Curator: Absolutely. The presence of this idealised countryside, even within the framework of a 'monstrous' frame, subtly connects to contemporary ideas of natural philosophy and ownership. Whose land is it, how is it portrayed, and for whose eyes is this vision created? These prints circulated as propaganda for lifestyles of the elite, offering tantalising glimpses into what some deemed "good taste." Editor: I never thought about prints being used in that way. I'm now curious how art affects design. Thanks for your insight. Curator: It’s a pleasure to offer another lens. This detailed print reveals not just aesthetic preferences, but the deep ties between art, power, and social display in the early modern period.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.