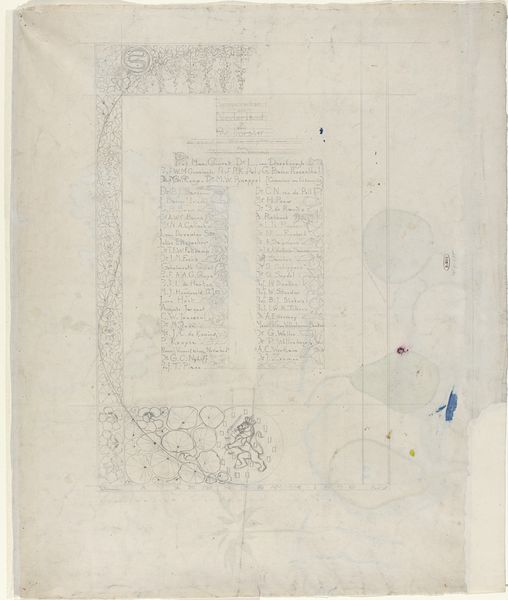

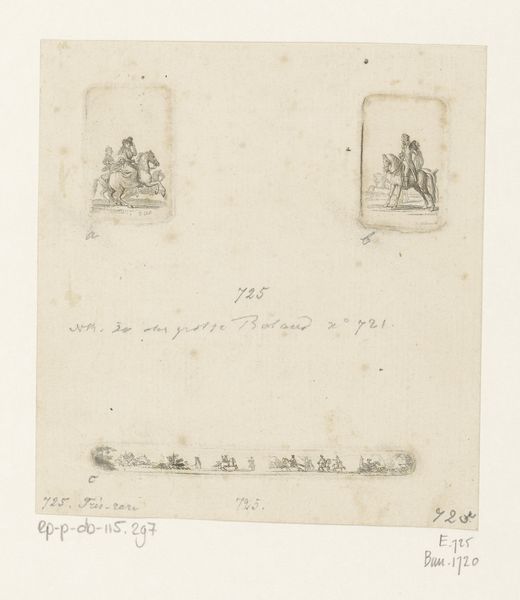

drawing, print, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

paper

#

ink

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 315 mm, width 480 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

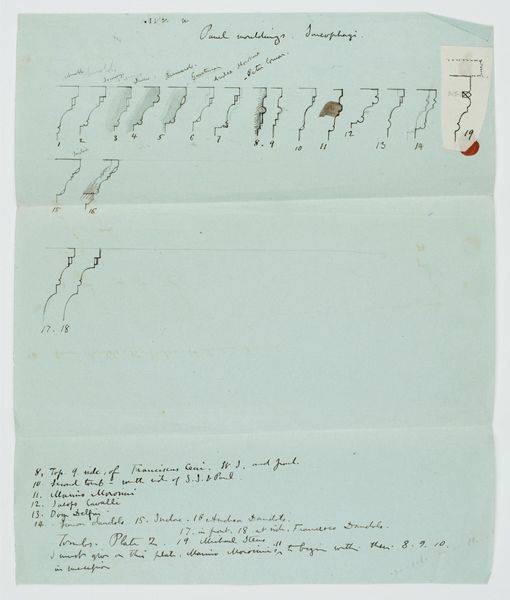

Curator: We're looking at "Rebus opgedragen aan Cornelis de Buyser," a drawing likely created around 1712 by Christoffel Lubienitzki. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It's whimsical! A cascade of images sketched in ink on paper. Like a visual puzzle, full of these tiny scenes and symbols that draw the eye in. It looks almost playful, despite the muted tones. Curator: The artist employs the rebus form, which was popular then—a visual puzzle using pictures to represent words or parts of words. So the 'playfulness' serves a specific function. We believe it’s a tribute, a kind of visual poem, dedicated to Cornelis de Buyser. This piece showcases a fascinating blend of the high art of allegory with popular culture and literacy practices. It speaks to the societal value placed on intellectual games and the creative ways people communicated. Editor: Looking at the careful construction of each symbol, it really emphasizes the relationship between the object and its visual representation. You have to study the images closely to understand the relationships and, ultimately, understand the intended meaning. How were these visual games disseminated at the time? Curator: Most likely these circulated within specific social circles, amongst those with the leisure and education to appreciate—and solve—the puzzle. Its materials—ink and paper—suggest a relative accessibility compared to, say, an oil painting, but its intellectual complexity restricts wider appeal, or consumption. You see, in this context, art functions as both commodity and communication, defining a class. Editor: True. Thinking about the composition itself, though, there's a clear structure that leads the eye through these riddles, despite their seemingly random arrangement. The careful arrangement of these figures generates a satisfying and cohesive image. And the consistent line work pulls it all together. Curator: Indeed. That aesthetic order provides the underlying structure of consumption, framing our reading as consumers of imagery. It creates a relationship with both the patron and the author of the Rebus in question. The imagery is not simply beautiful on its own, but carries this historical dimension we cannot disregard. Editor: It’s really the layering of these visual signifiers that leaves an impact, I think. It really encourages us to question the relationship between language, representation, and meaning. Curator: Precisely. The artistic decisions surrounding materiality reflect a social world in production. These materials give shape to the networks within which art is created, shared, and experienced.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.