print, photography

#

aged paper

#

paperlike

# print

#

typeface

#

landscape

#

photography

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

fading type

#

thick font

#

handwritten font

#

delicate typography

#

thin font

#

historical font

Dimensions: height 230 mm, width 190 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

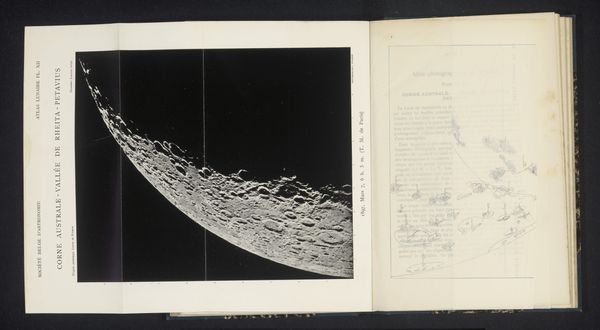

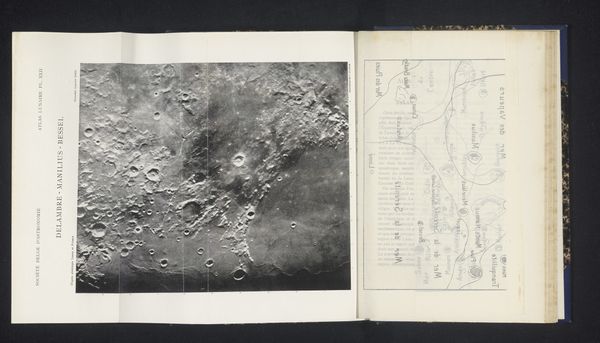

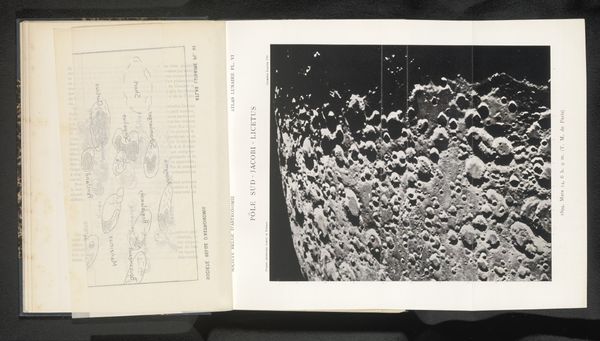

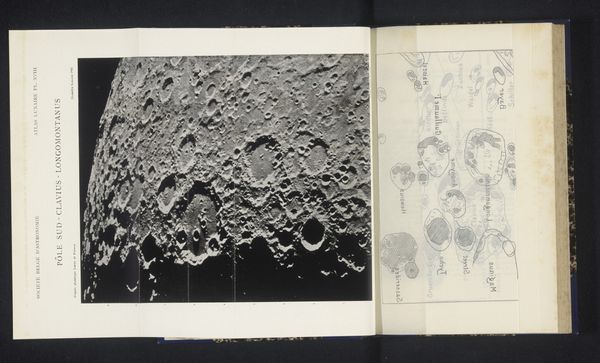

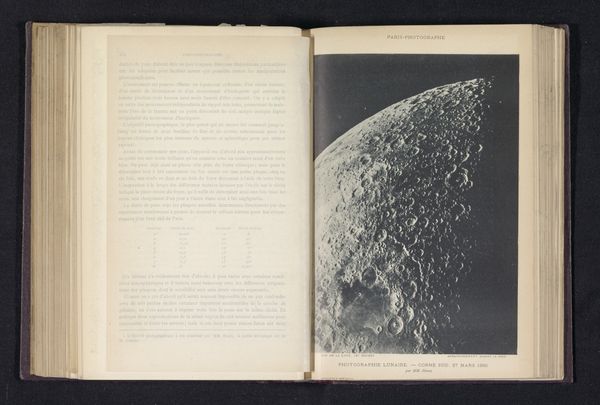

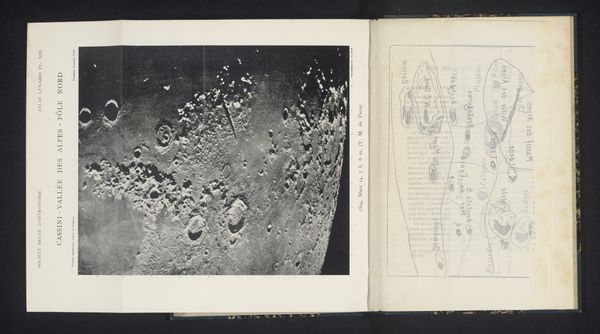

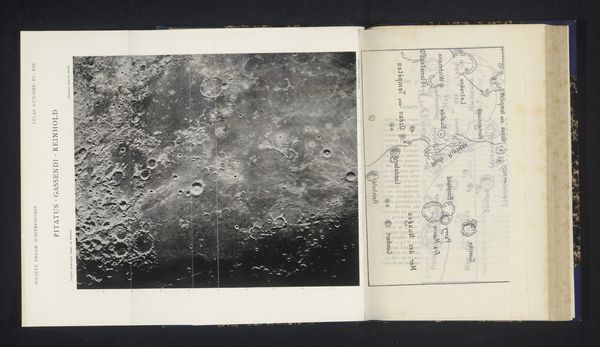

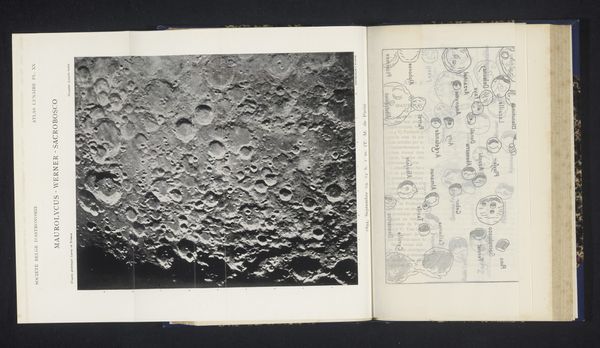

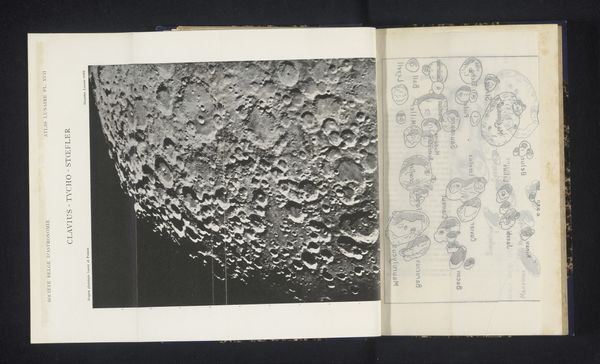

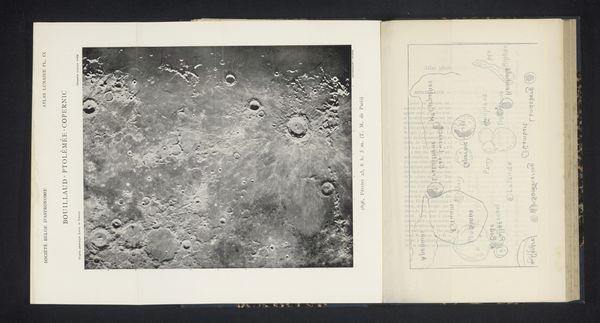

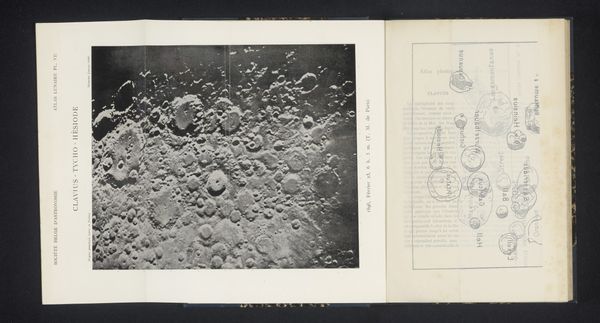

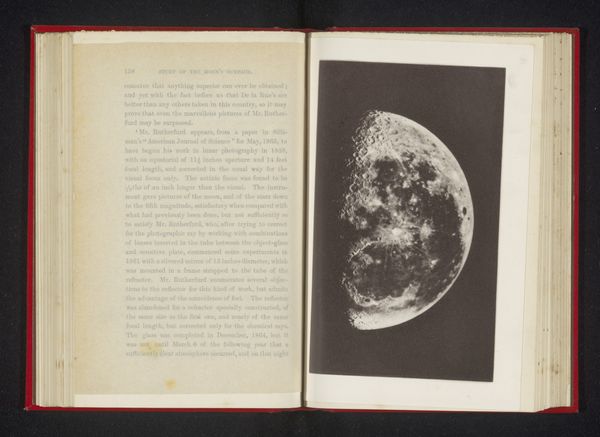

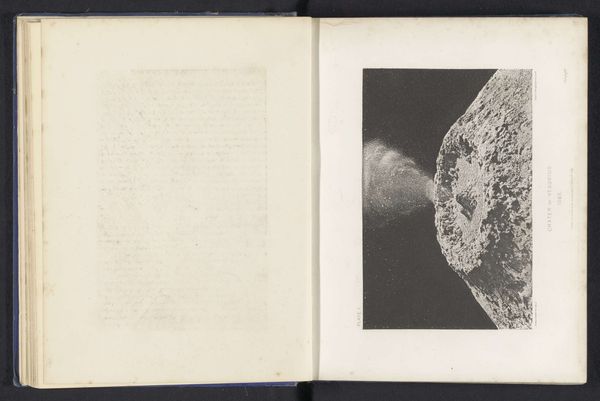

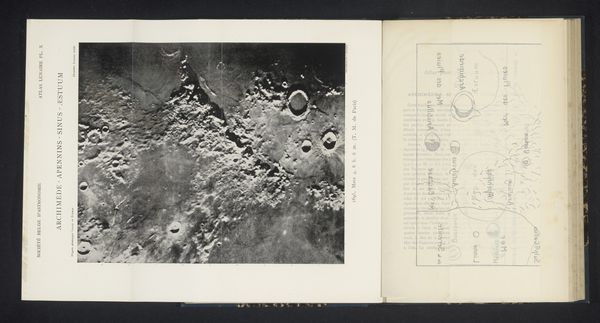

Curator: Here we have "Kraters op de maan," or "Craters on the Moon," created before 1900 by Loewy et Puiseux. What’s striking to you initially about this early photographic print? Editor: A certain melancholy pervades, don’t you think? That stark contrast between light and shadow across the lunar surface suggests the indifferent vastness of the universe. It's beautiful, of course, but in a way that underscores our own insignificance. Curator: That feeling resonates with the historical context. The late 19th century was a time of huge social and technological shifts, and anxieties. Seeing this objective, seemingly irrefutable depiction of the moon surely would have affected the collective consciousness of its place in the wider cosmos. Editor: Indeed. I’m drawn also to the handwritten annotations. They offer such a human counterpoint to the impersonal machinery of the photograph. The typeface evokes a specific era and aesthetic. It reminds me of early celestial cartography, of attempts to impose order on something immense. Curator: Absolutely, the act of naming and categorizing celestial bodies becomes a political act. It demonstrates the West's need to control not only land and people on this planet, but its impulse to chart and claim the territories beyond. These men were part of a large academic circle that helped build France as a dominating colonial presence. Editor: Precisely! Note also how certain formations appear highlighted or circled, as though the cartographer sought to prioritize some features over others. Even scientific observation is never neutral. This photograph feels more like an expression of its era than scientific pursuit. It reflects human intervention and a cultural preoccupation with exploration. Curator: And how advancements in imaging impacted identity during a period of increased globalization, shaping a sense of what it meant to be "modern." It reframes the narrative and complicates readings around positivism. It acknowledges humanity's reach. Editor: It does prompt reflection. Ultimately, the image is not merely of craters; it is of our historical ambition to map, to understand, and maybe to colonize even what lies beyond our immediate grasp. Thank you, the historical contextualization adds valuable weight. Curator: A worthwhile collaboration!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.