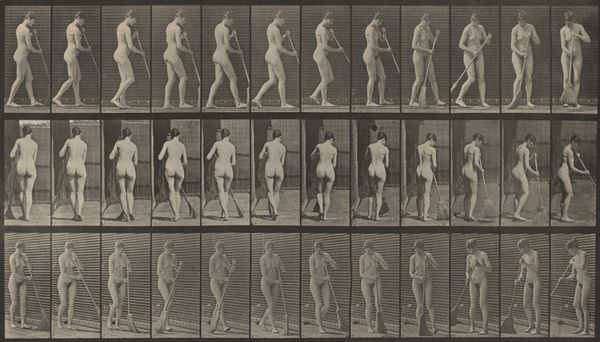

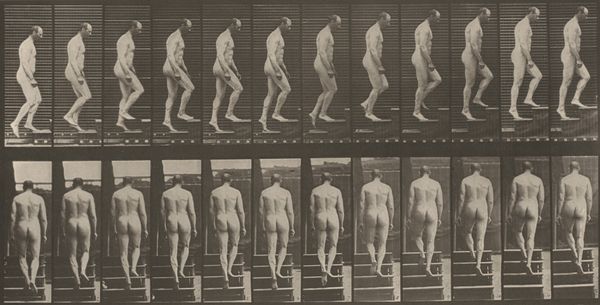

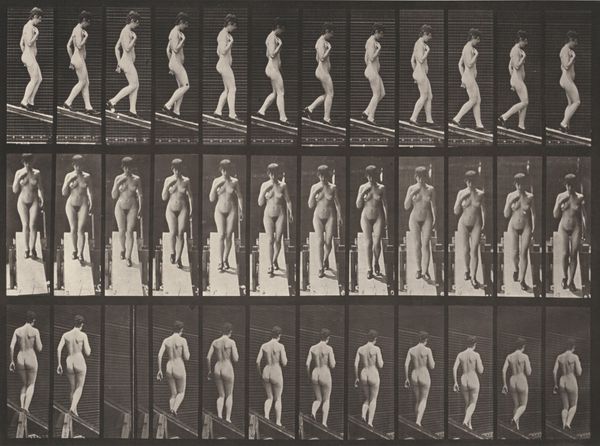

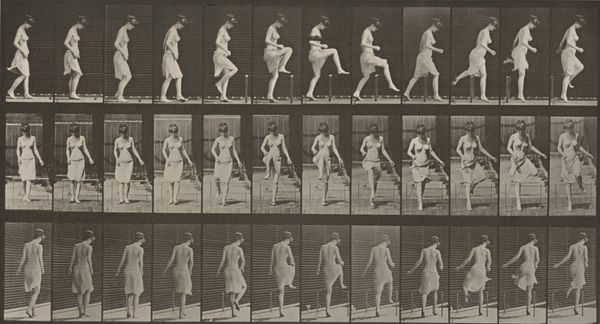

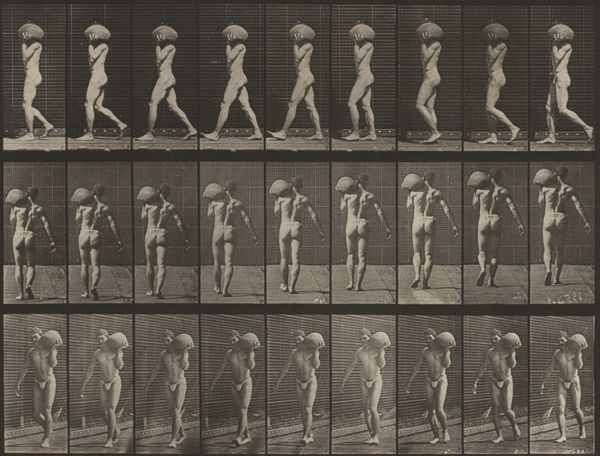

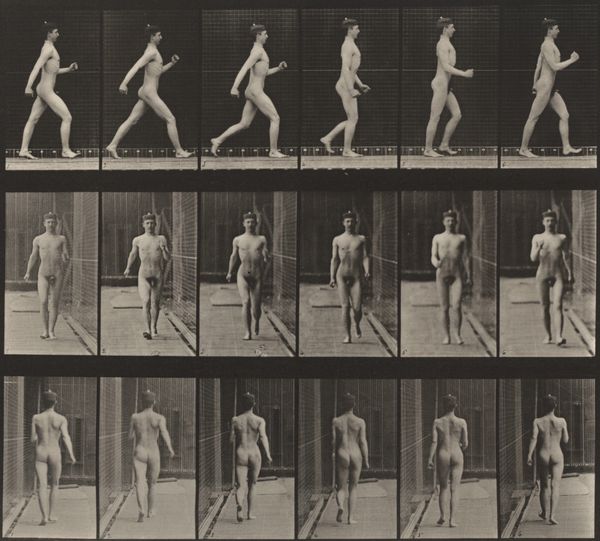

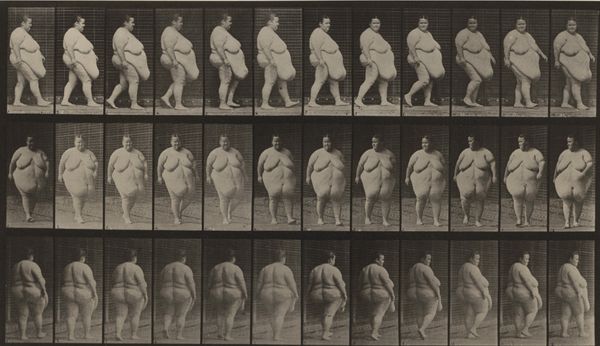

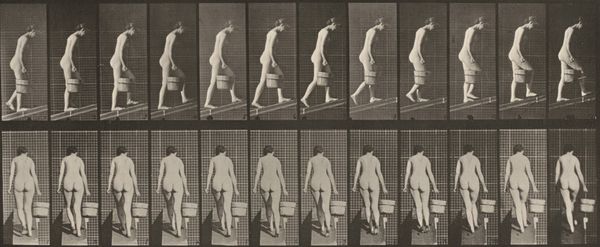

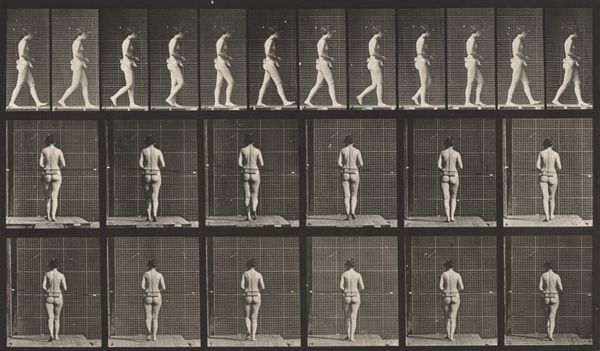

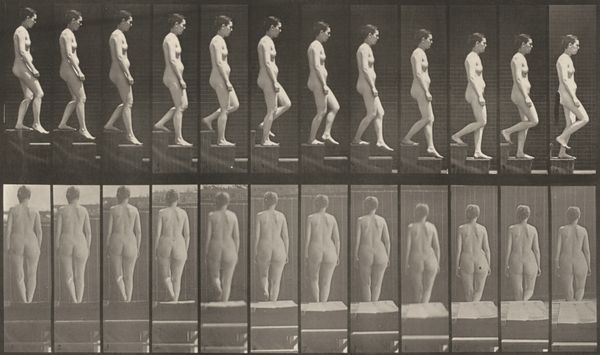

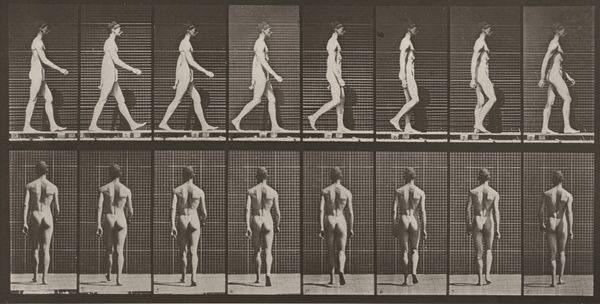

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

# print

#

sculpture

#

figuration

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

nude

Dimensions: image: 19.3 × 39.1 cm (7 5/8 × 15 3/8 in.) sheet: 48.5 × 61.2 cm (19 1/8 × 24 1/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

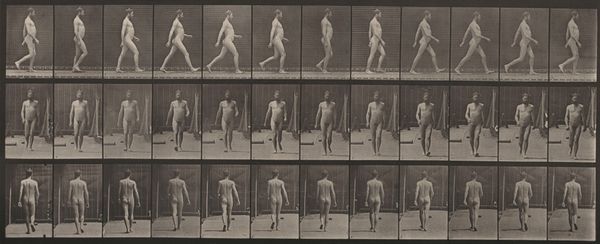

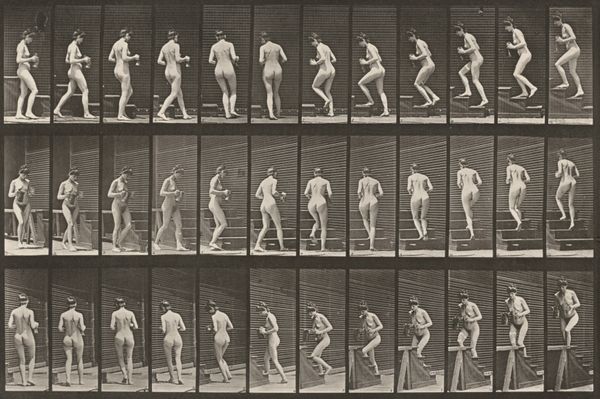

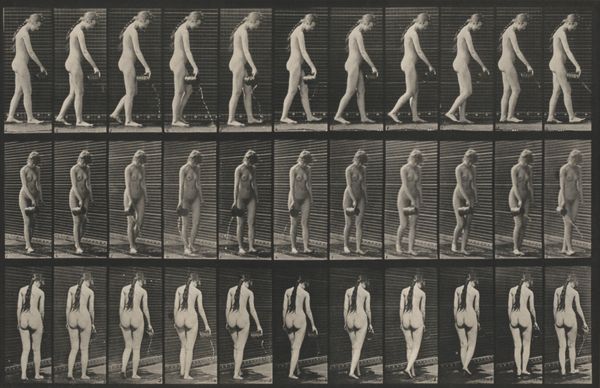

Editor: We are looking at "Plate Number 13. Walking," an 1887 gelatin silver print by Eadweard Muybridge. What strikes me is how clinical it feels. Almost like a scientific document rather than a piece of art. How do you interpret this work, particularly in the context of its time? Curator: It's crucial to understand that Muybridge's work transcends simple scientific documentation. Yes, it served scientific purposes, but let's consider the late 19th century, a period rife with discussions about the "primitive" versus the "civilized," often through a racialized and gendered lens. How does presenting a nude female form in sequential motion potentially reinforce or challenge these existing power structures and social biases? Editor: So, beyond just capturing motion, you're suggesting this work engages with ideas around the body, gender, and even Victorian societal norms? Curator: Absolutely. Photography itself was a relatively new medium. Consider the gaze – who is invited to look, and what does it mean to dissect a female figure in this way? Does the seriality and almost anatomical precision invite objectification, or can it be viewed as an empowering study of movement, disrupting the male artistic gaze that typically dictated how women were represented in art? And also consider how race plays into these social norms. Where would non-white bodies fit within Muybridge's work? Editor: I never thought about the perspective of the Victorian viewers and that contrast between scientific documentation and objectification. Curator: Exactly. It compels us to consider how science and art aren’t neutral; they operate within existing frameworks of power and influence. Muybridge's photographs become a powerful site for exploring those tensions and societal concerns, like gender dynamics and even colonial ways of seeing and cataloguing. Editor: It is so interesting to think of it now with all of this in mind, instead of seeing it simply as one of the early steps of photography and cinema. Thank you! Curator: Indeed. Viewing art as a historical document deeply embedded in its socio-political environment adds richer layers to its apparent simplicity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.