Copyright: Public domain

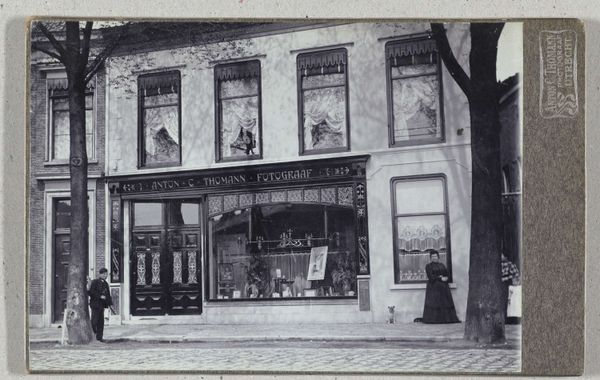

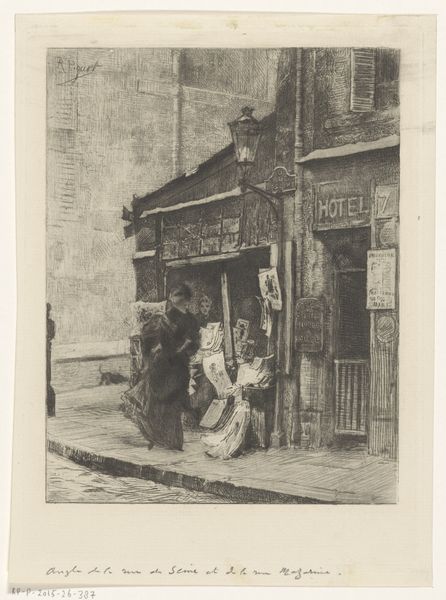

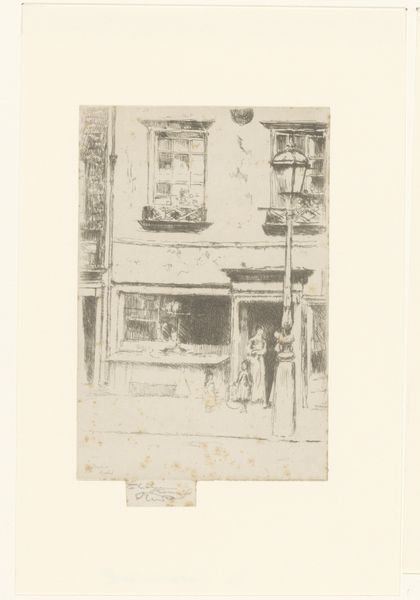

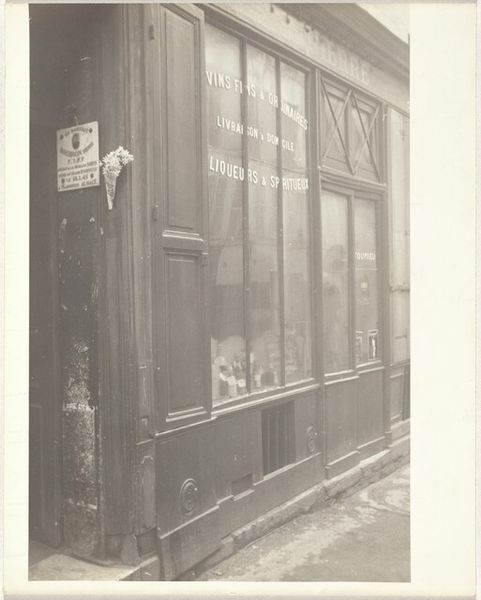

Editor: So here we have Nadar's "La Boutique De Nadar Pére à Marseille," from 1897. It’s a photograph, a daguerreotype I believe. It looks like a shop front… it’s quite striking, like a little stage. What catches your eye when you look at this piece? Curator: What strikes me is not only the photograph, but what it represents about labor and consumption at that moment. This isn’t just an image; it’s a documentation of the means of production – Nadar’s photography studio, his ‘brand’ on display through prints exhibited in the windows and on the facade. Think about the social implications: Who are the consumers here? The budding middle class seeking to have their portrait taken? Are these merely artistic portraits, or social signifiers, luxury goods? Editor: That's a fascinating point. It feels like a performance of "being seen." Does the daguerreotype medium itself impact this reading? Curator: Absolutely. The daguerreotype, unlike later photographic processes, produced a unique image. Consider the labor involved: the polishing of the silver-plated copper, the fumes from the chemicals...Each portrait was an original, carrying inherent value as a singular object. It makes me think about craft versus mass production. Nadar is presenting both his technical skill, and a glimpse into what photography could offer. But more than that, the viewer standing on the street becomes a piece of that production as well, don't they? Editor: I hadn’t thought of the material labor and its effects that way. Thanks, that gives me a new lens for examining photographic practices and their historical moment! Curator: Precisely. Analyzing the materiality reveals deeper social meanings within the image. It helps question what ‘art’ truly means to maker and audience, particularly during such eras of rapid innovation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.