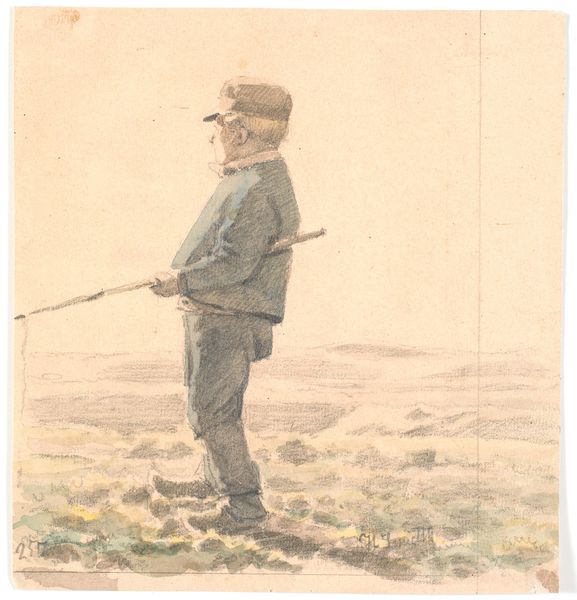

drawing, watercolor

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 232 mm (height) x 202 mm (width) (bladmaal)

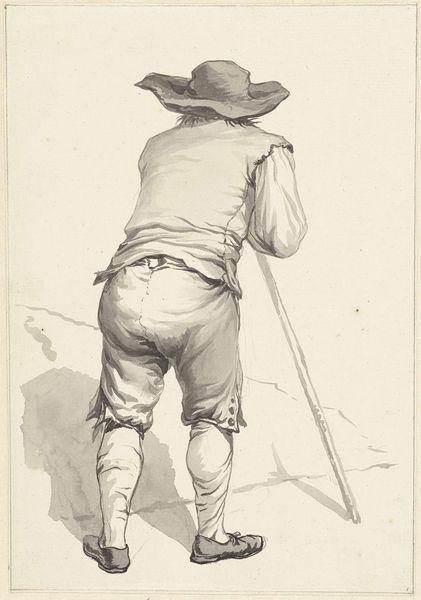

Curator: Standing before us is Johan Thomas Lundbye’s 1845 work, “Standing Shepherd Boy,” currently housed at the SMK. It’s a watercolor drawing. Editor: It strikes me as instantly poignant. There's something incredibly tender about the rendering, yet the boy’s posture hints at the difficulty inherent to his labor. Curator: Genre paintings such as this gained traction with the rise of the bourgeoisie. Urban audiences were very eager to gaze at what they took to be accurate reflections of the rural. Romanticism often idealized country life in particular. Editor: The materials themselves speak to that tension. Watercolor drawings weren’t exactly a durable or affordable medium for the sitter, suggesting it’s art made for consumption, romanticizing a labor far removed from the gallery visitor. It has that patina of bourgeois sentimentalism all over it. Curator: Precisely! The composition invites the viewer to partake in this very curated glimpse into peasant life, filtered through the lens of artistic and social conventions. The subtle use of line contributes to the soft depiction of its subject. It almost feels like an ethnographic document but obviously it is very posed. Editor: And there's labor involved in presenting rural poverty with such softness. Someone made this pigment, refined the paper, and perhaps even dictated the subject’s pose. Every medium is complicit, and romanticized ideas surrounding labor is very dangerous! Curator: I see it as also feeding into Denmark's own sense of national identity, constructing ideas around tradition. Consider the rise of national museums in the mid-19th century. Figures like this boy come to represent the common people within a national narrative, solidifying social structures. Editor: It makes you think about the role of art objects. Are they documents of historical record or tools of social manipulation? Regardless, this "Standing Shepherd Boy" is far from passive. Lundbye makes him present and we engage with all that entails when we stop and consider it. Curator: Ultimately, art acts as both. A reflection and an instrument. Lundbye captures a moment that offers much, perhaps unintended, commentary on the relationship between the Danish cultural elite and its labor force. Editor: So, the painting’s value extends beyond aesthetics to touch upon complex socioeconomic and political relationships of 19th-century Denmark, an aesthetic production inextricably tied to material production!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.