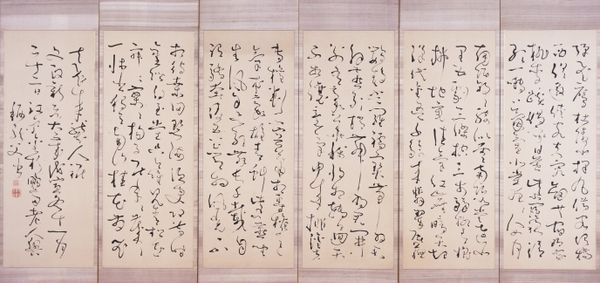

![Chang'an [right of a pair] by Kameda Bōsai](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzUyNjUxN2MxLTRlZTgtNDA3MC05YzQ1LThjNjc3NTk2OGYyOC81MjY1MTdjMS00ZWU4LTQwNzAtOWM0NS04YzY3NzU5NjhmMjhfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

asian-art

#

japan

#

paper

#

ink

#

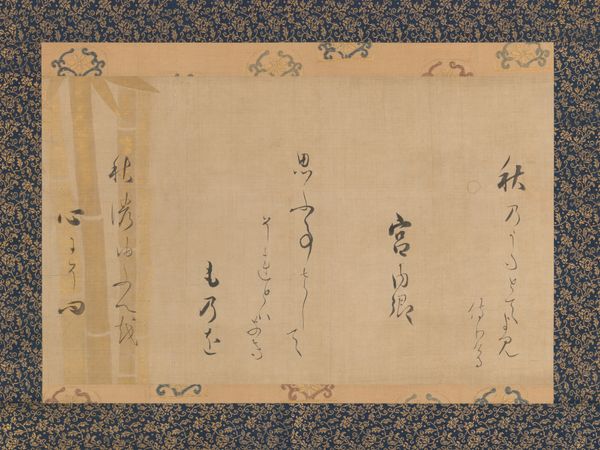

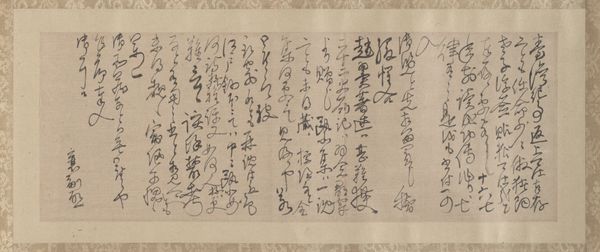

calligraphy

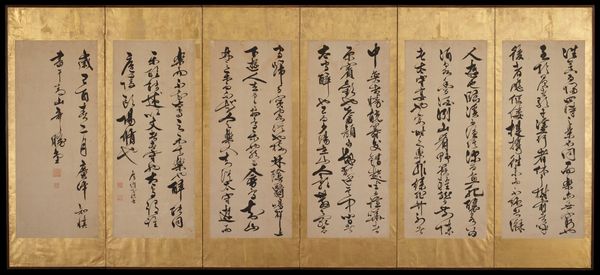

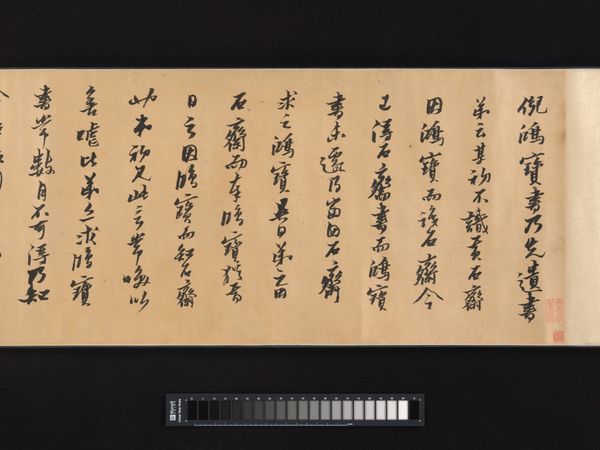

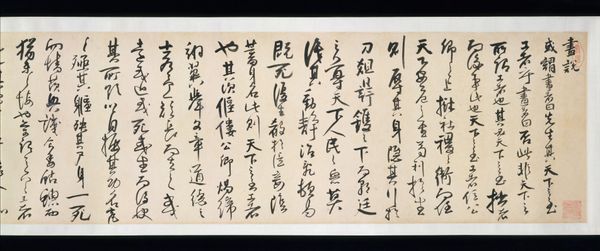

Dimensions: 53 7/8 × 123 3/8 in. (136.84 × 313.37 cm) (image)67 3/16 × 137 1/8 × 5/8 in. (170.66 × 348.3 × 1.59 cm) (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

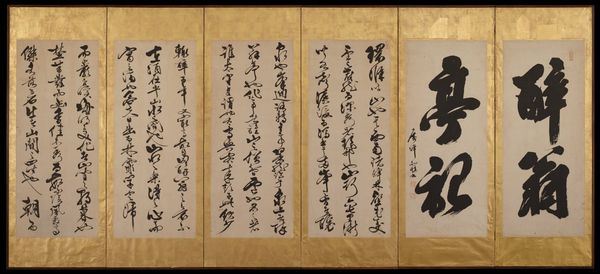

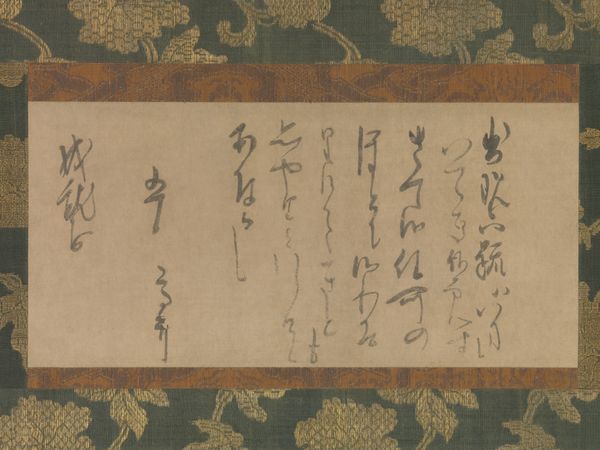

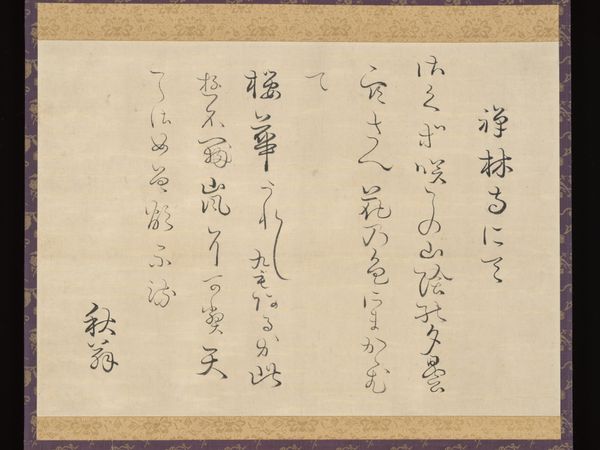

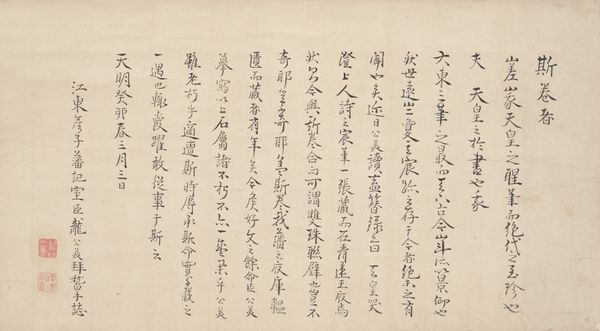

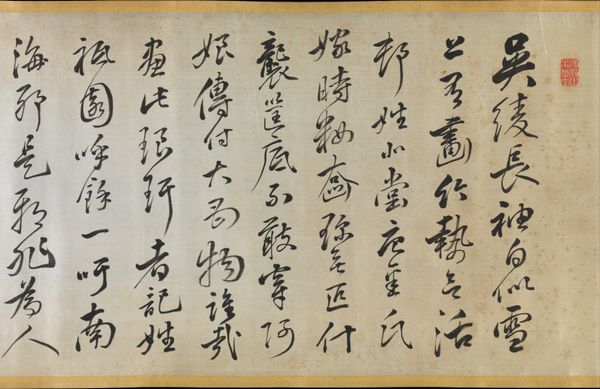

Editor: We're looking at Kameda Bōsai's "Chang'an," created in 1818. It's an ink drawing on paper and part of a pair. I'm struck by the energy of the calligraphy, the way the characters dance across the page. How do you interpret this work? Curator: Well, seeing calligraphy like this, we can start to understand literacy not just as reading, but as a political act in Edo-period Japan. Think about who had access to writing materials, to education, and the social structures that reinforced those inequalities. The choice of subject matter, even the *style* of writing, could be a form of resistance or conformity. Do you see any evidence of that here? Editor: I hadn’t thought about it that way. It feels very fluid and expressive, maybe even a bit rebellious in its departure from rigid forms. Curator: Precisely! Consider the social expectations of the time. Was Bōsai pushing against those norms? Was he maybe writing in solidarity with others facing social injustice or political constraints? What is known about their history in socio-political circles? Also, look at the composition – does the arrangement suggest a challenge to traditional aesthetics? Editor: I see what you mean! The composition feels unconventional. It really does make me wonder what statements this piece was meant to be making at the time. It's not just art; it's a statement of cultural and perhaps political identity. Curator: Exactly! And reflecting on what has changed between then and now makes it a living piece that raises contemporary considerations about identity and societal norms. Editor: It’s amazing how a work of calligraphy can be a window into social history. I’m glad to think of this in the context of political activism through art and what that looks like in modern works. Curator: It's all about context, really! By exploring the intersections of art, history, and society, we uncover deeper meaning.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

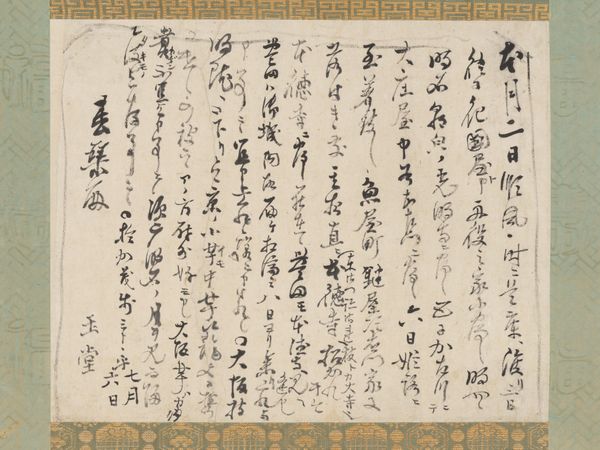

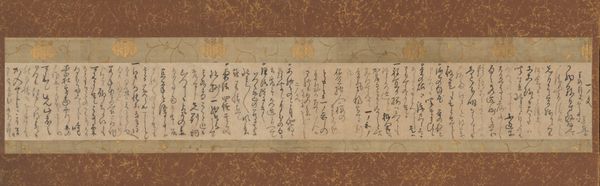

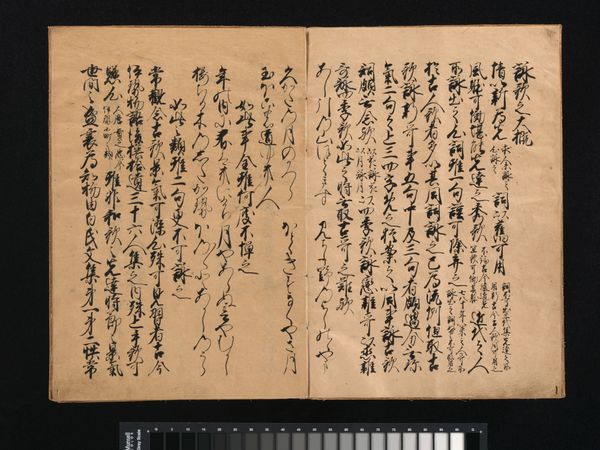

This pair of screens features the calligraphy of Kameda Bōsai, a Confucian scholar celebrated for his dynamic, vibrant handwriting. (Confucianism is an ancient philosophy and code of ethics that underpins the culture of China and its neighbors.) As a scholar, Bōsai was familiar with classical Chinese literature and culture and was a skilled calligrapher, painter, and poet in his own right. In this pair of screens he used the expressive “running” style of calligraphy, in which characters are abbreviated and multiple characters occasionally run together. The text is a transcription of a Chinese ballad (qilu) called “Chang’an, Ancient Theme” (“Chang’an guyi”) by Lu Zhaolin (c. 634–684). The city of Chang’an, today known as Xi’an, was significant to the Japanese—two of Japan’s early imperial capitals, Heijō and Heian (now the cities of Nara and Kyoto, respectively), were designed after this ancient Chinese capital city.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.