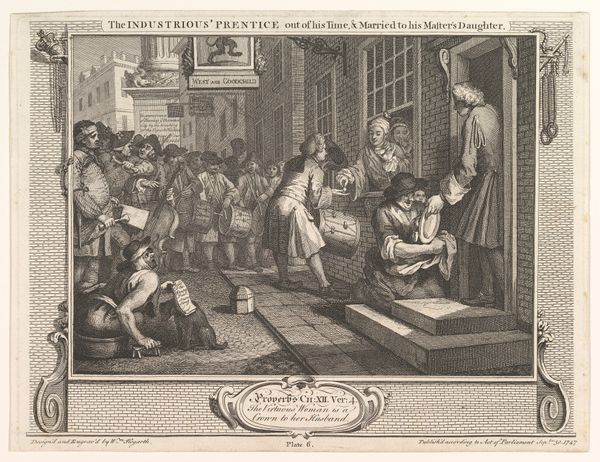

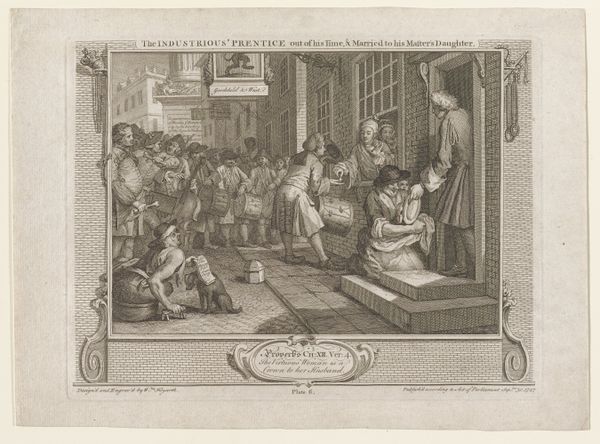

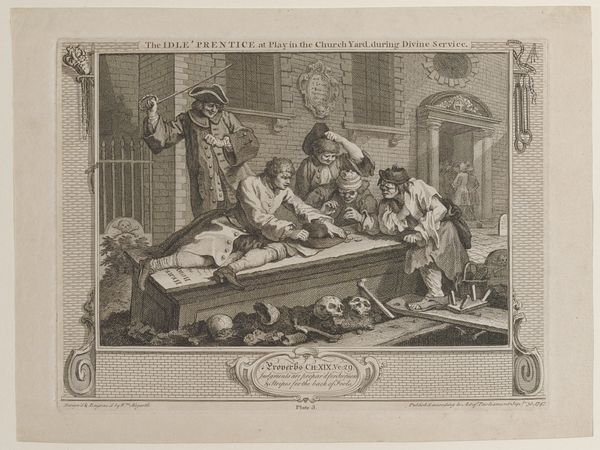

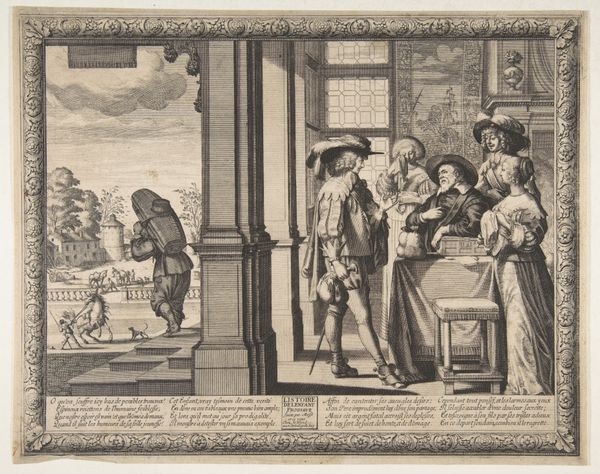

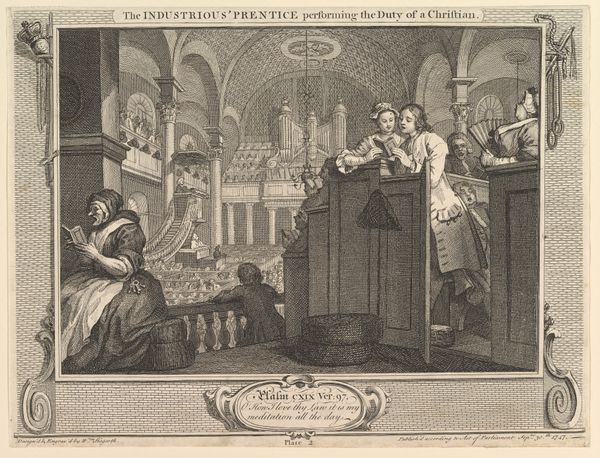

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

caricature

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: sheet: 10 1/4 x 13 3/4 in. (26 x 35 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Look closely at this 1751 engraving by William Hogarth, titled "Paul Before Felix Burlesqued." It's currently held here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What's your immediate take? Editor: What strikes me first is the blatant skewering of power—the robes, the gestures, the composition, everything suggests an absurd machinery. Hogarth certainly wasn't mincing words, or lines, in this print. It feels raw in its criticism and funny. Curator: Hogarth was never one to shy away from a good satire. You notice how he dubs it as being in “true Dutch taste?” It's a dig, right? English artists at the time felt pressured to emulate classical styles, especially history painting which Hogarth subverts by claiming the style for himself. He transforms a New Testament scene into this almost comical… puppet show. Editor: It makes one consider Hogarth's own status in the art market. Prints, and engravings in particular, democratized artmaking—disseminating imagery beyond the wealthy elites and directly to a growing middle class hungry for... gossip and critique. That makes Hogarth himself somewhat of a revolutionary as artisan, producer, and distributor, challenging traditional ideas around patronage and artistic license. The social context is really intrinsic to its significance. Curator: Absolutely! Hogarth saw himself as more than just an artist; he was a social commentator, crafting morality tales. This isn't just about mocking the Dutch style; it’s about challenging hypocrisy. His work allowed him the chance to poke fun at established norms by poking fun at visual expectations—the "serious" stuff like history paintings. I mean look at the angel assisting Saint Paul! Even he’s struggling. Editor: He’s not idealizing, he's really leveling the playing field, even deflating what we expect holy and powerful figures to be—both compositionally and socially. What strikes me is how the engraving process itself becomes complicit in this debunking act—lines become the conveyors of criticism and humor rather than just mere representation. Every etched detail contributes to this biting satire. Curator: And that level of detail is what rewards repeated viewing. You keep discovering new levels of commentary, new targets for Hogarth's pointed wit. You notice the devil writing notes. It's layered, like peeling back the layers of a bad system. Editor: Exactly! You’re invited to question what constitutes artistic skill, devotional scenes, authority—it's all beautifully tied to his choice of material, technique, and audience, not just "high art" standards. It suggests the meaning lives not just in what he depicts, but *how* and *for whom*. I'd say his radical vision made him, in many ways, more than an artist. He was a savvy social inventor who utilized material production and artifice in the process of image creation. Curator: Indeed. In this small, potent print, Hogarth isn’t just offering an artwork; he’s sparking a revolution in thought. Editor: So much conveyed via ink, paper, and sharp critical humor. A very provocative package, that really makes one think.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.