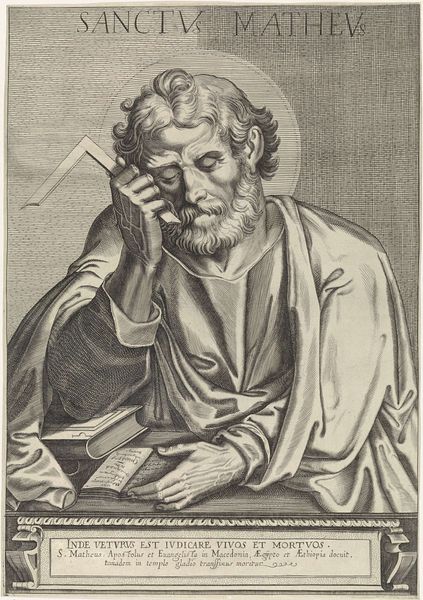

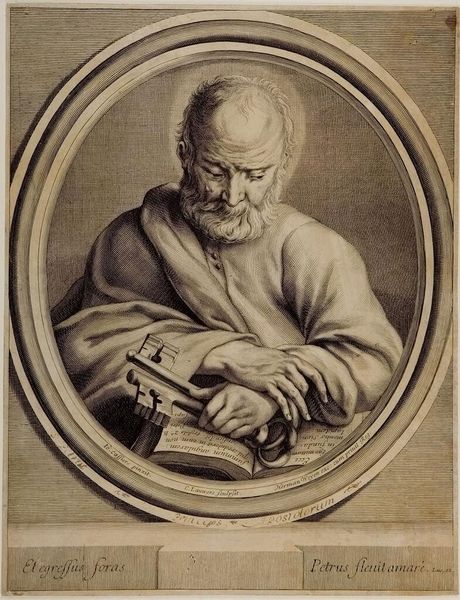

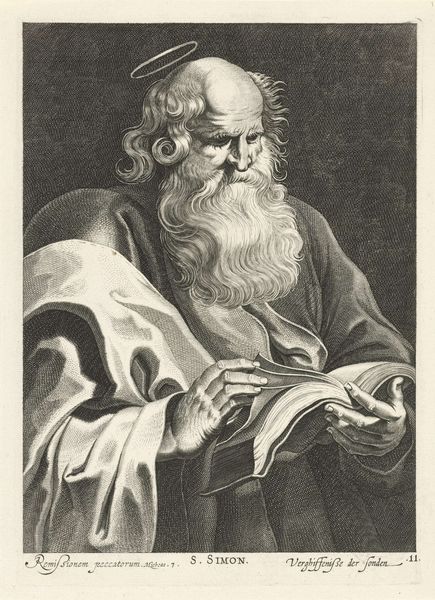

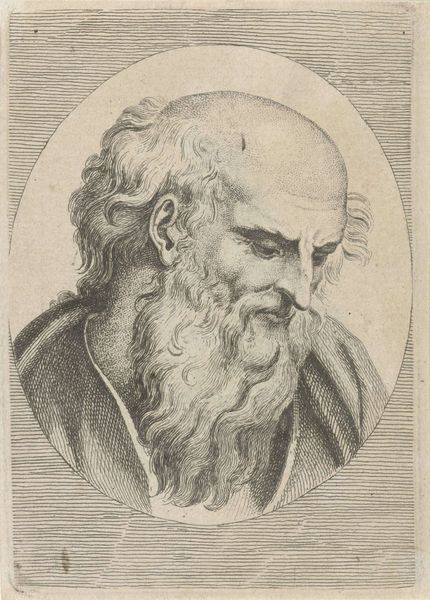

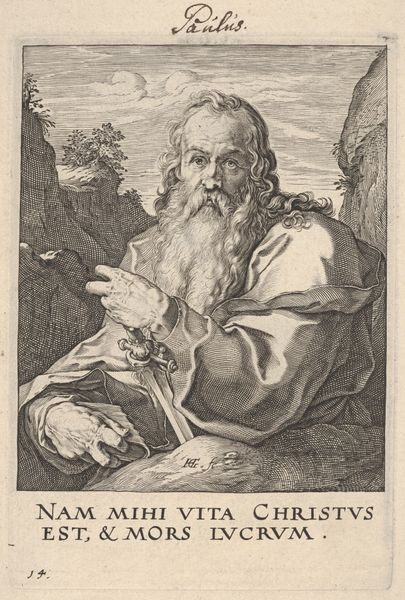

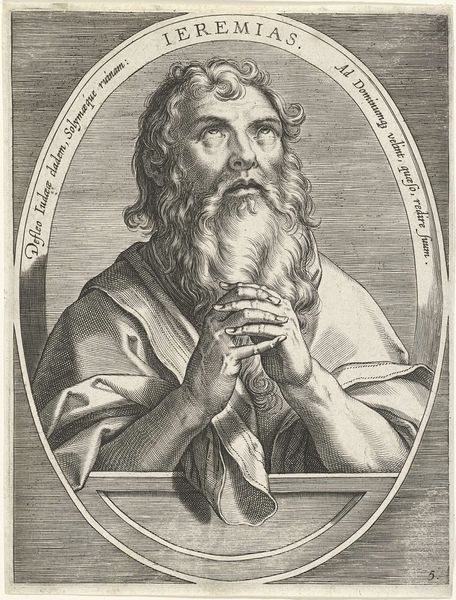

drawing, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

portrait image

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

portrait drawing

#

charcoal

#

history-painting

#

portrait art

Dimensions: height 233 mm, width 166 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

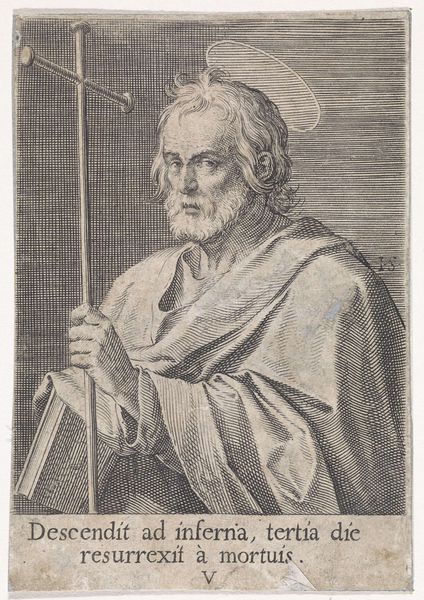

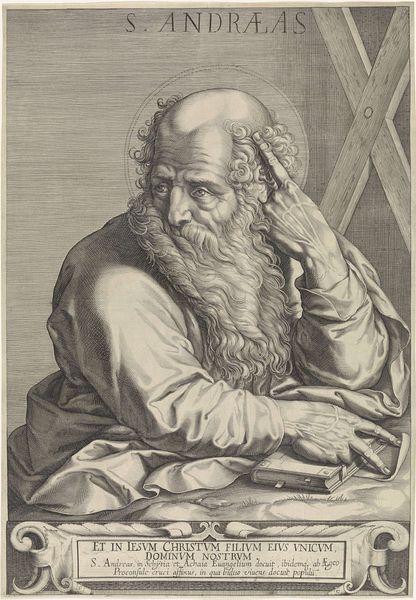

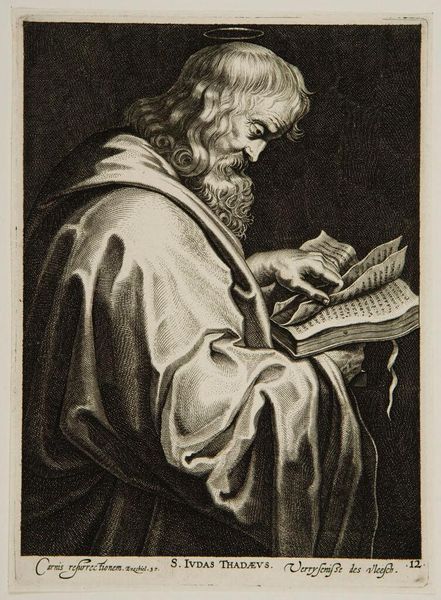

Curator: Standing before us is a drawing from between 1650 and 1800, titled "Apostel Petrus," found in the Rijksmuseum collection. It’s attributed to an anonymous artist. Editor: My first thought is that the face holds incredible weariness. The charcoal work really captures the folds of his skin and the weight of his gaze. And that key—so prominent. Curator: Indeed. The image employs charcoal in the baroque style, fitting a pattern we often see of history painting merging with portraiture. We're meant to see not just a man, but Saint Peter himself, keeper of the keys to the kingdom of Heaven, an apostle weighted with the church's immense responsibility. Editor: Thinking about that key...look at its stylized form, almost architectural. It speaks to authority, yes, but also craftsmanship. Someone physically made that key, someone labored over it, imbued it with symbolic power. The means of its creation matters just as much as its intended use. It's more than mere metal; it's a made thing imbued with cultural power. Curator: Absolutely. The depiction echoes traditional portrayals of Peter, which were circulated, especially during the Counter-Reformation, asserting the Church's authority amidst religious turmoil. The visual language reinforced that institution's power. Editor: And let's not overlook the choice of charcoal. Its very ephemerality as a medium contrasts sharply with the lasting authority Saint Peter represents. Was that a conscious choice to underscore human frailty against divine structure? I’m wondering if it meant something particular about access to art materials at this point too, given the expense of, say, paint. Curator: That's insightful. It suggests an interesting tension—the institutional power presented is anchored to earth with all of its material implications of accessibility. Perhaps even a meditation on mortality itself? Editor: Precisely. It all folds back into thinking about the making—the materials used, their accessibility, and the artist's choices to depict this figure in such a particular way. Curator: Considering its circulation and historical context illuminates the ways in which art actively shapes social and religious ideologies, rather than passively reflecting them. Editor: And for me, thinking about the material, combined with that gaze, really helps personalize a religious icon that could feel very distant otherwise. Curator: It’s a powerful convergence of the divine and the deeply, physically human.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.