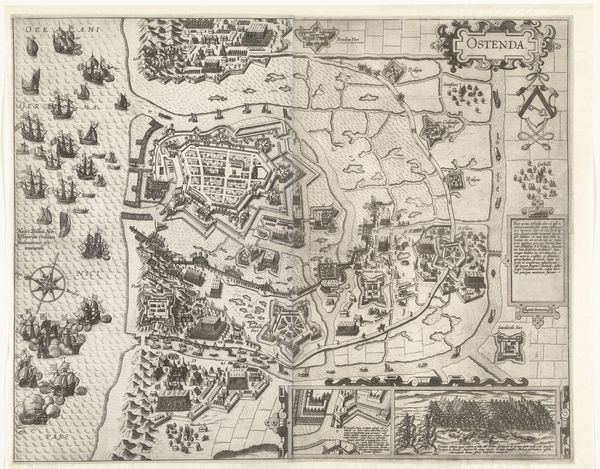

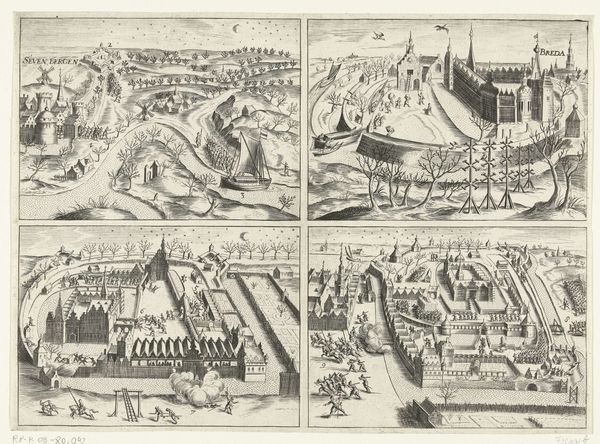

print, ink, engraving

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

ink line art

#

ink

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 278 mm, width 358 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

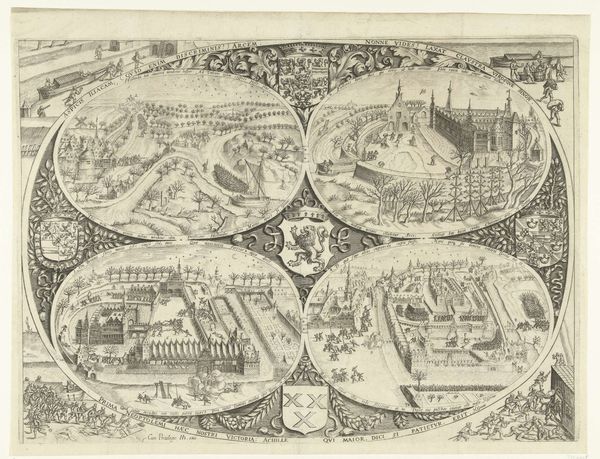

Curator: Here we have "Afbeelding van alle door Spinola veroverde steden in 1620-1621," a print created in 1621 and now held in the Rijksmuseum collection. It's an anonymous engraving in ink. Editor: My initial impression is how meticulously detailed it is, even in its miniature scale. There’s a fascinating tension between the geometric order and the chaotic scenes of conquest depicted. The texture, rendered through the ink, gives a sense of depth despite its flat, graphic quality. Curator: Absolutely. From an art historical standpoint, this image presents itself as both cartography and history painting. Its existence tells us about early modern conceptions of power and representation. Who held that power, and for whose consumption was this created? Editor: That's a really important entry point to discussing the socio-economic conditions under which art like this could exist. Look at the details in those little vignettes, like small industrial activities are nestled alongside depictions of military conquest. The labour is so prominent here. This print speaks volumes about the entanglement of material wealth with the theater of war. Curator: Yes, that conflation is significant. We can understand it as not merely a representation of military victories, but also as a celebration of Spinola's power, meant to shape and solidify a certain image of him within the broader sociopolitical context. Was he interested in anything but expanding this reign, what of those who resisted this narrative of colonization and forced industrial production? Editor: Exactly! And look at the methods involved to make and reproduce this, and we begin to consider this work within a much wider network. This wasn’t just about memorializing events; it was also a method for communicating a particular narrative, using artisanal skills and material means. Curator: Indeed. Considering the broader historical implications here forces us to rethink these scenes as active agents in history and cultural memory—propaganda tools that played a tangible role. What stories do these images reproduce? Whose realities are amplified, and whose are omitted from the record? Editor: I appreciate how examining the physical labor embedded in this piece makes us consider the distribution of this kind of political power in material ways. It pulls back the curtain on the reality beneath the glory of war. Curator: Precisely, looking at it through this perspective allows us to better grasp how artwork serves not only as cultural records but also political instruments during its specific context. Editor: By considering production, the image, even with all the problematic power dynamics it promotes, reveals the story of its own making, an almost unintended critique.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.