drawing, ink, pencil

#

drawing

#

form

#

ink

#

geometric

#

pencil

#

line

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 418 mm, width 290 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

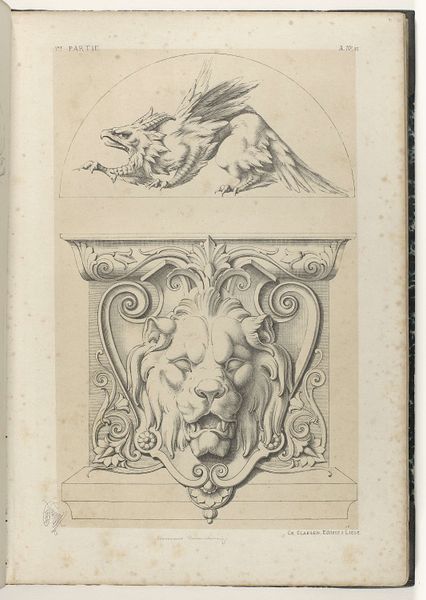

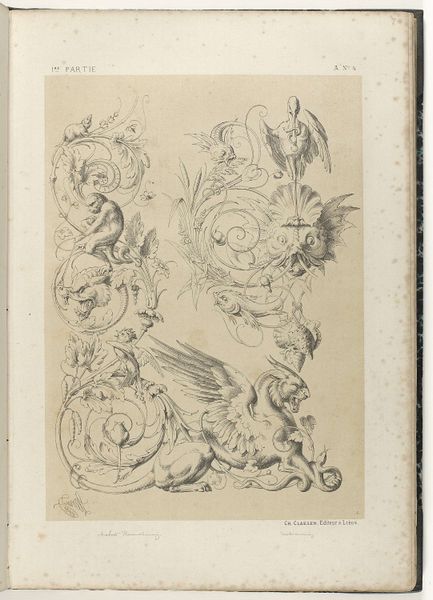

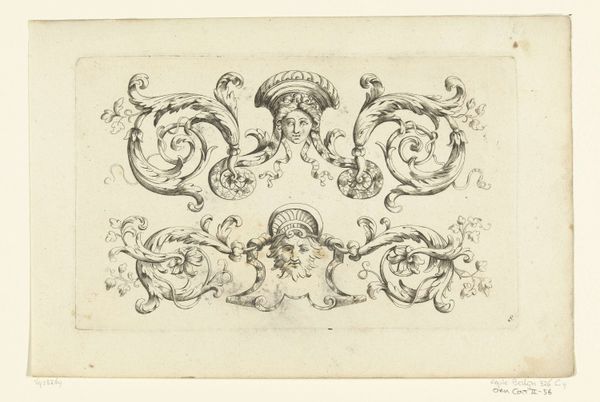

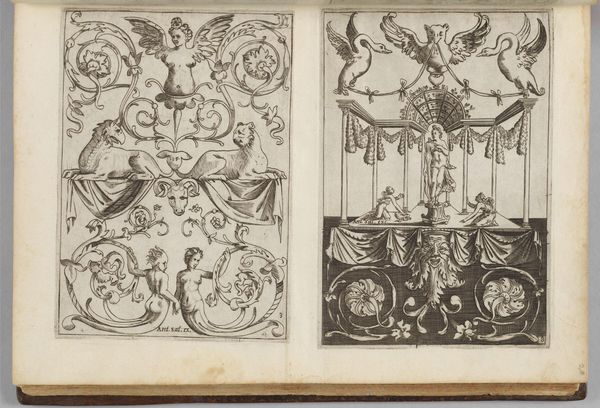

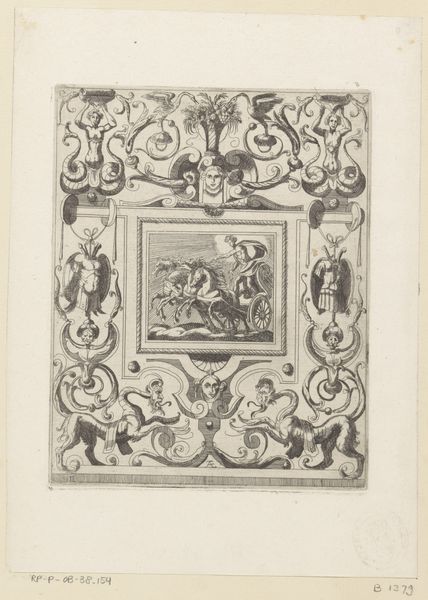

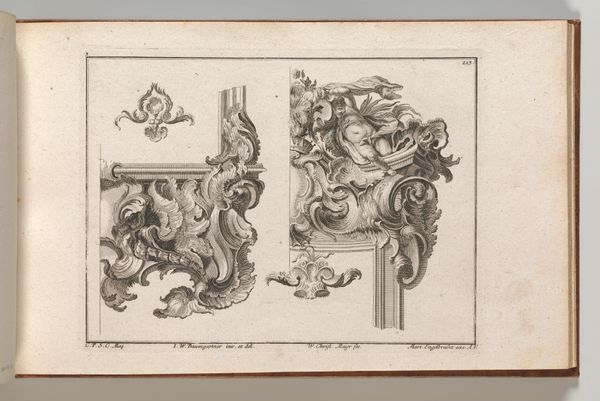

Curator: This detailed 1866 drawing, titled "Vijf ornamenten voor gebouwen," or "Five Ornaments for Buildings," is by Michel Liénard and executed in ink and pencil. What's your immediate reaction? Editor: A strange collection! My eyes are immediately drawn to these chimerical figures—part lion, part bird—they feel both regal and monstrous. Curator: Indeed. Liénard’s rendering speaks to the revival of classical forms during the mid-19th century. The precise linework emphasizes craftsmanship, highlighting how architectural details become commodities, readily reproduced and applied. These ornaments, while seemingly fantastical, reflect the burgeoning industrial capacity to mass-produce decorative elements. Editor: Precisely! Look at the symbolic weight of each figure. The griffin, a guardian of treasure, perhaps reflecting the era's obsession with wealth and status. And these grotesque fish heads, lurking with a menacing stare! One can’t help but wonder about the psychological impact these were meant to create. Curator: I’m interested in that impact. Think about the foundries that cast these designs, the workers who replicated Liénard’s drawings in iron or stone. It is intriguing to imagine these once hand-crafted ornaments duplicated endlessly, losing some of their unique character as they adorn buildings throughout Europe. The reproduction undermines its aura as a special hand-made design. Editor: Yet, even in reproduction, the images retain a powerful presence. The serpent entwined in the griffin, for instance, signifies wisdom and immortality, constantly reminding the building's inhabitants, no matter how reproduced. This kind of symbolic language resonates throughout history. Curator: It reminds us of the shift in artistic labor. Here is one craftsman providing the design for hundreds of workers to reproduce, each adding his bit, but unable to call the overall result entirely their own work. It illustrates new relationships between labor and aesthetics during that era. Editor: That is a compelling point. But beyond the economics of it all, what stays with me is how Liénard’s careful execution invites us to engage with the history of myth itself. It continues to challenge our imaginations. Curator: Absolutely. It's through exploring production processes that we see echoes of past mythologies. Editor: And the drawings invite us to imagine future iterations of myth.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.