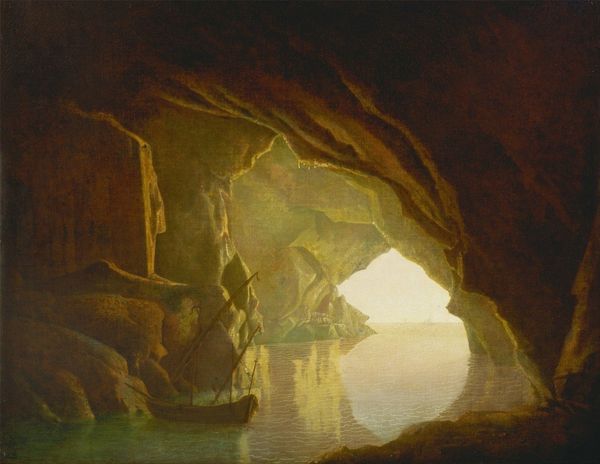

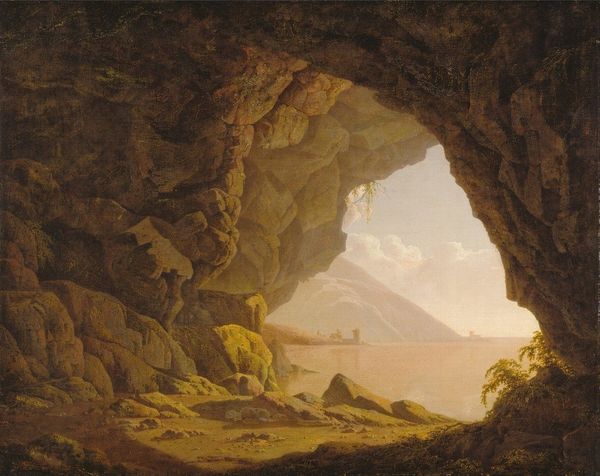

A Grotto in the Gulf of Salernum, with the figure of Julia, banished from Rome 1780

0:00

0:00

josephwrightofderby

Private Collection

Dimensions: 175 x 114.3 cm

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Oh, this is affecting. Wright's "A Grotto in the Gulf of Salernum, with the figure of Julia, banished from Rome," painted in 1780. Look at that chiaroscuro! Editor: My goodness, the sense of utter isolation is palpable. A single, frail figure amidst the imposing darkness of the grotto. Curator: Indeed. The dramatic lighting—a hallmark of Wright's style—guides our eye, doesn't it? The stark contrast between the inky blackness of the cave and the almost ethereal light emanating from the sea...it’s incredibly deliberate. The painting employs light not only to reveal form, but to create a moral narrative about emotional strength. Editor: One has to wonder, however, about that figure. Julia, exiled—a woman deprived of power, made to inhabit a lonely periphery. And, of course, we have to remember the conditions for female artists at that time—was there an empathy towards women in socially vulnerable positions, a silent protest against restrictive cultural structures? Curator: The grotto itself becomes almost a character in this scene, a framing device almost. Consider the sharp, angular rocks against the fluid, almost luminous quality of the water. There’s a clear formal tension between stability and change, the temporal versus the eternal. The emotional register here is palpable in the forms. Editor: True. The way Wright positions Julia, almost as a tiny supplicant before a vast, indifferent nature, speaks volumes. Her banishment from Rome reflects more than just a personal tragedy. Curator: The narrative weight it carries, filtered through its structure—the interplay of light and shadow, the textural contrasts—makes it a prime example of Wright's unique Romantic vision. He doesn’t offer sentiment, but rather, shows its construction. Editor: So, we see Julia not only as a woman in exile, but as a symbol—or maybe a warning—about the precariousness of power and the social constraints. Wright turns the personal into the political. A woman's private despair turns into public spectacle of power at play. Curator: Yes, indeed. Thinking purely in structural terms it all just serves to accentuate the overall design! Editor: Thank you, both Wright and you, for giving us a fresh look into this period, and the stories that live beyond a canvas.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.