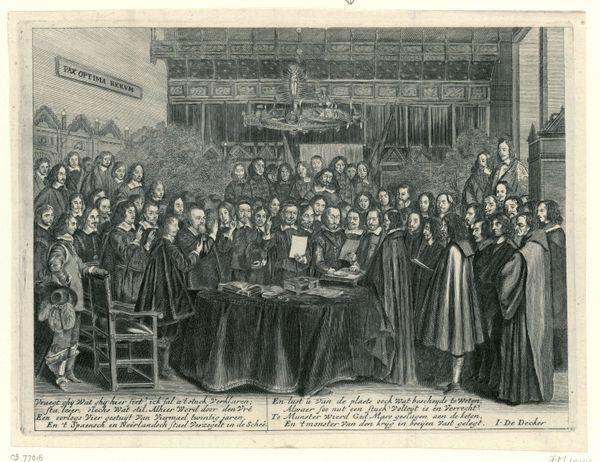

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

portrait reference

#

group-portraits

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 470 mm, width 585 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this engraving by Jonas Suyderhoef, made in 1648, titled "Beëdiging van de Vrede van Münster, 1648"… I’m immediately struck by how carefully ordered this gathering appears, despite the clear import of the moment. The weight of history seems palpable. Editor: Indeed. The almost overwhelming mass of figures, all those similar faces gazing intently, certainly gives it a serious tone. But did you notice how, amidst the sea of dark clothing, a central figure appears brightly illuminated, bathed in divine light almost? It gives the impression of a sacred moment. Curator: A Baroque print commemorating a monumental historical event: the Peace of Münster, solidifying the end of the Eighty Years' War. It wasn’t just a treaty; it formalized the Dutch Republic’s independence, reshaping the European political landscape. Think of how deeply that impacted Dutch identity and trade for centuries. Editor: Absolutely. You know, seeing all those faces, you get the sense it’s more than just an event, it is also the representation of peace as a symbol, a hard-won agreement becoming this powerful image to represent a monumental political event. And what do you make of the banner at the top of the image? It almost gives the image a triumphant flair, yet a rather peaceful one at that. Curator: The inscription "Pax optima rerum", Peace, the best of things. Perfectly sums up the public sentiment, surely? Remember how artists worked as chroniclers but were also embedded in that public? The printing press aided in amplifying images like these as vital records, influencing opinions. Editor: It’s a fascinating choice of wording, as "optima rerum" can have layers of meaning. I cannot help but feel that there is some degree of skepticism to its presence, a desire, perhaps for the treaty to really work, not only through an administrative decree, but for people to fully realize its impact in practice, which is not guaranteed by simply establishing an accord. Curator: The visual symbolism dovetails into that, definitely. It is always a bit tricky with such group portraits; we have to be wary of reading our desires into past events. Still, knowing the subsequent Golden Age and maritime expansion of the Dutch Republic adds further gravity to Suyderhoef's depiction. It marks a point of no return in European affairs, immortalized by Baroque means of representation. Editor: Well, for me, that touch of doubt keeps the work dynamic; beyond the posed seriousness and its historical weight, there's a very human call towards sincere and long-lasting peace. It makes me look for signs of genuine hope on all those faces!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.