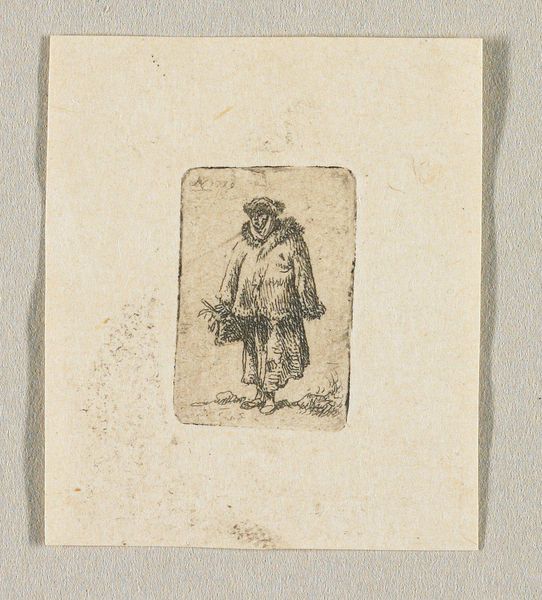

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

pen-ink sketch

#

15_18th-century

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 28 mm, width 15 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this rather unassuming print by Jean-Pierre Norblin de la Gourdaine, created in 1779, entitled "Standing Man in a Long Fur Coat," one gets the immediate impression of delicate yet purposeful lines. Editor: Indeed. My first thought goes to the tangible presence of the fur itself—I can almost feel the heft of it despite the medium's inherent flatness. Was fur such an evocative material then as it is today? Curator: Absolutely. Fur in the late 18th century held significant social weight, visually broadcasting wealth and status within specific societal hierarchies. This image likely depicts someone of considerable standing, though the sketch-like quality perhaps hints at something more subversive, less formal. Editor: It's compelling to think about how printmaking itself democratized images of wealth. Engravings allowed for wider circulation, perhaps even subtly challenging those hierarchies you mentioned. How would this have been made? Curator: As a print, it was probably created using engraving techniques. The labor involved in making such detailed works was really something. We tend to view them now as precious historical artefacts, not as commercial objects created in a competitive print market. Editor: Exactly. I am really drawn to this apparent tension; a readily accessible medium used to capture an elite commodity. Considering this interplay illuminates the social undercurrents rippling beneath the surface of what at first looks like a simple portrait. How would these prints circulate? Did they have particular audiences in mind? Curator: Certainly, prints like these played a role in circulating ideas about fashion, class, and social roles. Sold independently or bound in volumes, they provided visual commentary on contemporary life, subtly shaping social discourse within salons and public spaces. It offered accessible ways for the emerging middle class to aspire to emulate upper-class modes of dressing. Editor: Interesting. To me, thinking about who manufactured the coat, as well as who consumed these images—the social lives of makers as well as models, opens up a range of compelling historical questions that challenge conventional narratives surrounding the printmaking production and fashion. Curator: I think you’re spot on. Seeing art as intrinsically woven into those complex historical relationships—museums, galleries, cultural taste—lets us look past any established art-historical narratives and start new conversations. Editor: Precisely. Engaging with it beyond surface level allows for critical thinking, not just about aesthetic presentation, but about production, context, labor, and meaning in the world around us.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.