drawing, etching, ink

#

drawing

#

etching

#

landscape

#

ink

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

romanticism

#

15_18th-century

Copyright: Public Domain

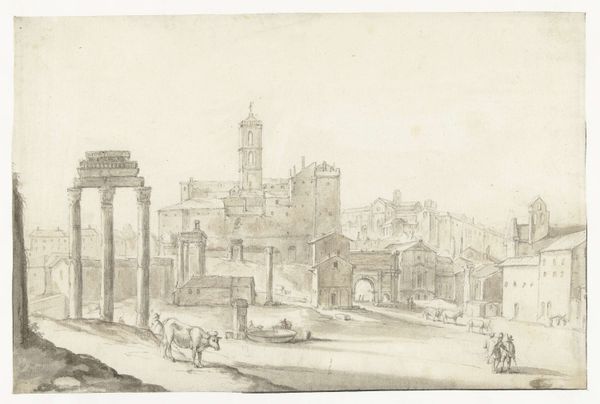

Curator: The work before us is titled "Antike Ruinen vor einer Landschaft," which translates to "Ancient Ruins Before a Landscape," attributed to Franz Kobell. It is part of the Städel Museum's collection. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: There’s a certain lightness to it. The delicate lines, almost like whispers on the page, give the ruins a somewhat ephemeral quality despite their obviously solid, stone construction. It makes you wonder about the hands that worked those lines and about those ruins themselves, and why they are pictured. Curator: Well, considering that Kobell was active primarily during the 18th century, we can see the emergence of Romanticism in this style, with ruins used as allegories and symbols. He most likely would have worked primarily with etching and ink for its easy reproductions to share works such as these with a wider audience, enabling others to ponder classical societies, how societies rise and fall, and even perhaps moral virtue itself. Editor: Interesting. From my perspective, the materials themselves—ink and paper—play a crucial role in our perception. The seeming ease of its production obscures what would have surely been harsh labor for quarrying, sculpting, and finally building this construction from so long ago, and even the simple depiction serves to transport these reflections through time. Do you see those figures at the front, obscured in the landscape and under shadow? Curator: I do. Perhaps, they also underscore a more significant cultural context. At the time, there was a surge of interest among the nobility to depict Italian settings within landscapes, even using similar materials. However, the artist has intentionally shifted the ruins to the foreground, centering the ancient remains instead of prioritizing its Italian location. This is an attempt to engage more meaningfully with a more thoughtful understanding of art and ancient cultures. Editor: That really calls into question who he was producing art for, as well as to consider just how widely distributed these pieces would be, beyond nobility and through to various emerging, intellectual societies and middle-class audiences, as the tools themselves were made more readily available through material trade. Curator: An important point to consider indeed. Seeing the ways these scenes become symbolic images within the market opens an interesting path for how history is shaped. Editor: Precisely! These images allow a wider accessibility of social values and tastes to spread far beyond an isolated art object to an almost globalized aesthetic sphere through reproduction. It truly shifts art to a critical mode within our own lives. Curator: A perspective well-earned after such rich engagement. I leave contemplating just how significant the accessibility of its creation allowed such imagery to influence generations onward.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.