drawing, print, graphite

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

caricature

#

pencil drawing

#

graphite

#

portrait drawing

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 580 mm, width 420 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

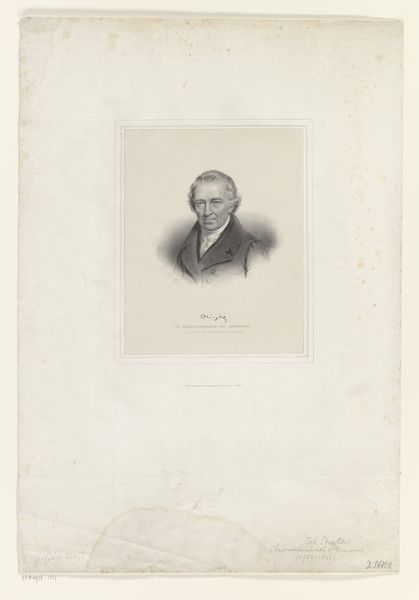

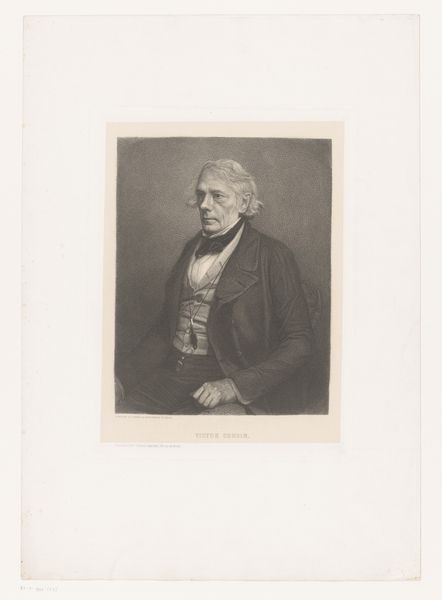

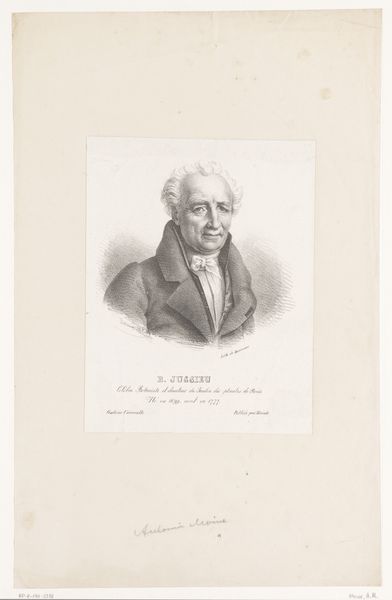

Curator: Here we have an intriguing portrait from between 1839 and 1850 by Franz Chevalier, titled "Portret van Christian Friedrich Segelbach." The work is graphite, a pencil drawing rendered as a print. Editor: The gaze really strikes you first, doesn't it? It's the kind of portrait that seems to capture a certain… resignation, perhaps. There's a somber quality in the eyes and the tight set of the mouth. I notice the precision of line, but overall I find its feeling austere, removed. Curator: Indeed. This print very much reflects the ideals of Neoclassicism as well as aspects of realism. Segelbach’s features, while idealized to a degree, have a clarity that suggests careful observation, and this aligns with academic art’s emphasis on formal correctness. The somber quality is typical, a symbolic reminder of serious-minded civic duty. Editor: Civic duty often being a tool for social control. I am thinking about who could have had access to this work. Segelbach appears to have been someone of stature. The work serves as a declaration of status in a period rife with political upheaval and class struggle, where the rising bourgeoisie increasingly commissioned portraits as signs of their own ascendance. Is he aware that his portrait in this style could symbolize an assertion of the ruling class? Curator: It is plausible. However, portraiture had very set symbolic languages tied to cultural norms. Beyond simply documenting appearance, portraiture serves to perpetuate ideas and convey messages. Segelbach's face seems not to follow any conventional formula; yet we may examine the sternness and formality of the period itself, with an understanding of the role such portrayals played within 19th-century European social dynamics. Editor: But aren't portraits also often a dance of self-presentation, revealing less about the subject than about how they wanted to be seen? Here the use of grayscale helps achieve a kind of detached, ideal portrait. Curator: Perhaps. Symbols speak in layers. This piece allows us to meditate on how we encode identity through representation. Editor: It's true, these images are really cultural echoes, prompting conversations about their origins as well as our perceptions today. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.