drawing, print, paper, ink, pencil, graphite, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

graphite

#

pen

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 203 × 226 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

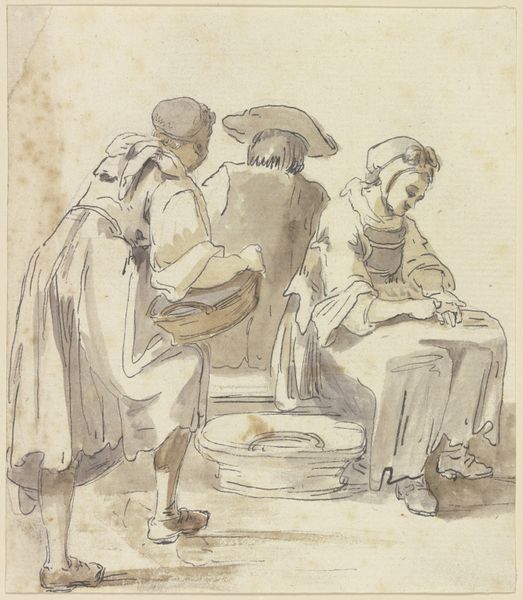

Curator: This is “Four Peasants,” a drawing of uncertain date by Augustus Wall Callcott, currently held here at The Art Institute of Chicago. It's rendered with pen, pencil, and ink on paper. What’s your first take? Editor: There’s such a stark contrast here. The standing figures have this air of detached observation, almost indifference, while the seated peasant is actively pleading, looking upwards. It immediately evokes questions of power and class. Curator: Indeed. Callcott was working in a period when artists increasingly depicted the everyday lives of common people. It's fascinating to consider the social dynamics he presents, reflecting the romanticized views of peasantry but also highlighting their inherent social inequalities within evolving capitalist structures. Editor: Right, and what are they thinking? The figures are turned away, not inviting any sort of immediate connection, and even if this drawing reflects that era’s class structure, I find myself frustrated by the passivity in the other figures. Curator: That emotional complexity is precisely where art creates crucial intersections, wouldn't you agree? Consider, for example, how such visual imagery impacted socio-political ideologies or perceptions about marginalization at the time this piece was created. It's a document, not necessarily a reflection of pure lived experience, but one of public social life. Editor: Of course, of course. Thinking about art as document is really essential. These are clearly not idealized figures, not posed portraits. The clothing, the faces--they suggest an authenticity in representing rural life. Curator: Absolutely, the detailed execution allows us to engage with figures who aren't caricatures, they have texture to their lives, their social condition. As a period document, pieces like Callcott's gives critical insights into societal perspectives of commoners, or what roles art plays in the circulation and potential shifting of social power. Editor: Well, the work invites a sort of tension, I think—a need for justice. Which maybe isn’t such a bad thing to be left with. Curator: I think that makes for a brilliant reading, to think about social action stemming from art. A powerful interpretation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.