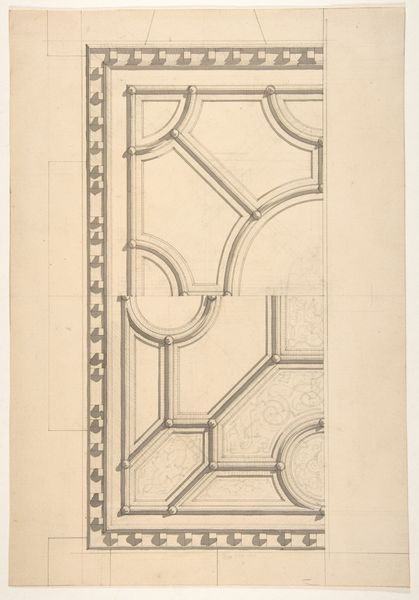

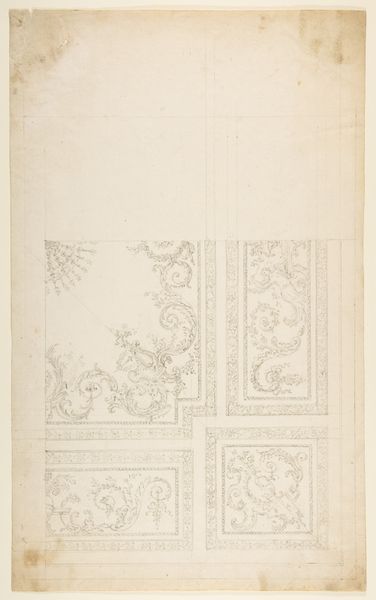

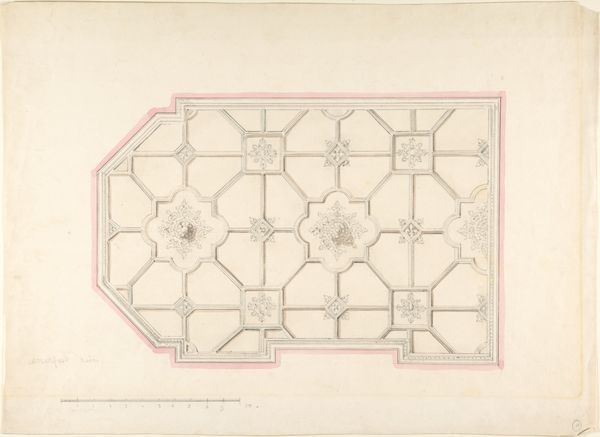

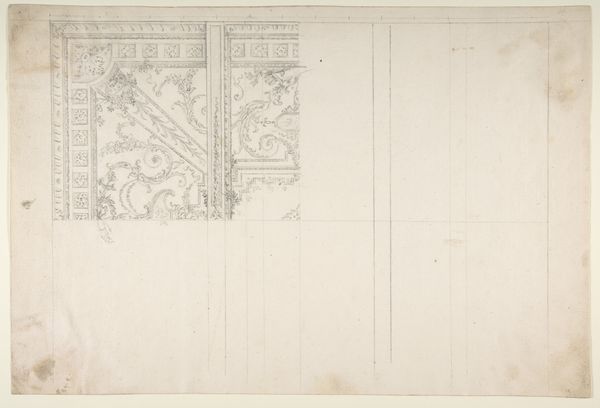

Partial design for the decoration of a ceiling 1830 - 1897

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

light pencil work

# print

#

classical-realism

#

paper

#

geometric

#

pencil

#

line

Dimensions: Overall: 11 3/16 x 9 3/16 in. (28.4 x 23.4 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Looking up, or perhaps imagining ourselves doing so, brings us to Jules-Edmond-Charles Lachaise’s "Partial design for the decoration of a ceiling," dating roughly from 1830 to 1897. It’s rendered in pencil on paper and housed right here at the Met. Editor: My first impression? It’s ghostly. A fragment of a dream, or perhaps a blueprint for one. You almost feel like you could breathe on it and the design would simply fade away. So light, so preliminary. Curator: Absolutely. What’s interesting here is considering the public function of such a design. Lachaise likely wasn't creating art for art's sake but offering a visual proposal, aiming to shape someone's experience of a space. Think of the power dynamics involved—convincing a patron that *this* ceiling design would enhance their prestige. Editor: It's fascinating how something intended for such grandeur is presented with such fragility. It whispers more than it shouts. These floral motifs held within the diamond grid, are they striving for harmony or a structured perfection? Is that achievable on a ceiling, above us all? It speaks volumes, this partial design. There is a very intimate moment contained within the boundaries of the print. Curator: Right, and what does it mean when that intent intersects with prevailing artistic trends? Classicism never really went away, right? These geometric forms and symmetrical arrangements reflect a Neoclassical sensibility that dominated much of 19th-century design. A ceiling wasn't just a covering, it was a canvas for projecting cultural ideals. Editor: And what ideals are we projecting here? The safety of structure and tradition? Or is this the seed of rebellion? Because, for me, it feels that the artist, in his execution is questioning those strict, constricting lines. It may be an underlying thing. A beautiful drawing nonetheless, it holds complexity. Curator: It’s true. I mean, to truly appreciate the impact, one has to consider how lighting and color might play across these delicate lines. That subtle use of shading can transform flat geometry into something truly three-dimensional. That’s what would give the completed decoration its actual power. Editor: Thinking about this drawing as it exists now makes me grateful for art history and our conversation together because without it, a mere fragment of some long-gone aspiration lives and breathes here. Curator: Precisely. A fragment perhaps, but a compelling window onto the aesthetics and aspirations of its era.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.