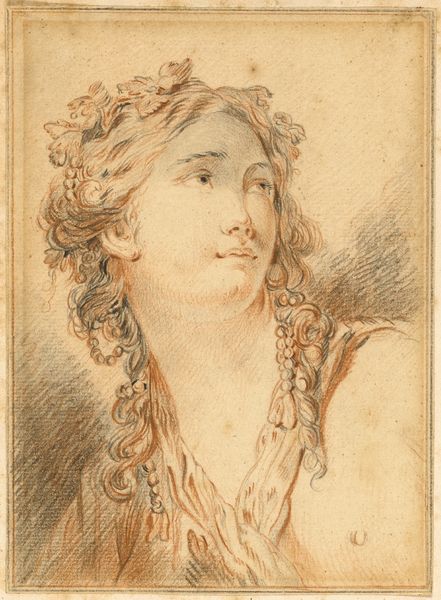

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

nude

Dimensions: height 210 mm, width 157 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Bernard Picart's "Halffiguur van staande naakte vrouw," a pencil drawing dating from 1683-1733. It's delicate, almost ethereal. I’m interested in how he achieved this effect with just pencil. What do you see in this piece, considering the materials? Curator: For me, it’s compelling to examine this drawing as a commodity within its historical context. The paper itself, likely handmade, represents a specific level of material wealth and access. Consider the labor involved in producing that paper and the pencil used to create the image. What kind of societal structures allowed for such specialized craftsmanship? Editor: So you're saying the drawing is interesting not just as a representation of a nude woman, but as evidence of a whole production chain? Curator: Precisely! The red chalk pencil, the source of the pigment, even the type of wood used to make the pencil—all these material choices reveal insights into trade routes, artistic training, and social expectations. Who would have purchased this drawing, and why? Was it a study for a larger work, or a standalone object of desire and display? Editor: It's almost like reverse engineering the supply chain of the 17th and 18th centuries by analyzing art materials! Did Picart's choice of red chalk signify anything beyond aesthetics? Curator: Red chalk allowed for warmer tones, but its availability also hinged on specific mining operations and distribution networks. Was this local material or imported? Analyzing its materiality helps us understand the artwork's placement within systems of labor, production, and consumption. Editor: I never thought of a drawing like this having such deep ties to economics and labor. Thanks to you, I have a fresh viewpoint on the work as more than a traditional nude drawing! Curator: Indeed. By interrogating its materiality, we unravel broader cultural narratives embedded within. It opens exciting possibilities for future readings of art history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.