Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

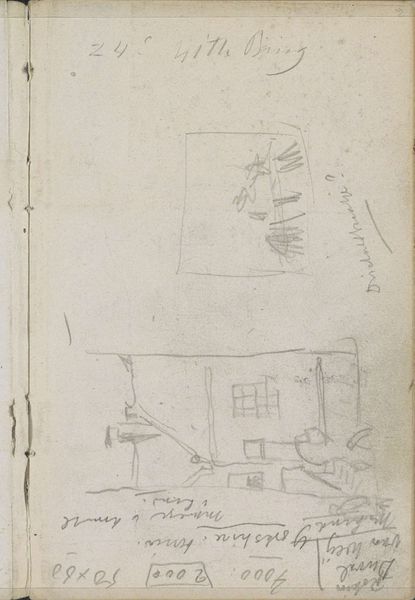

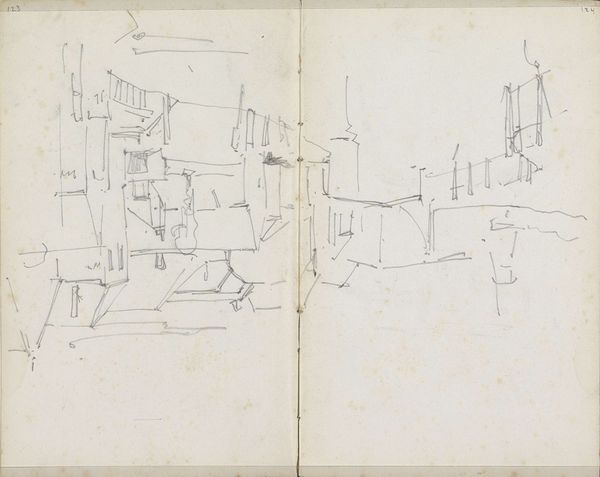

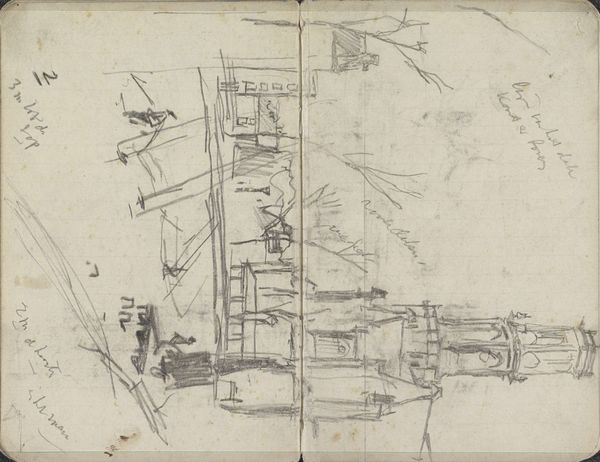

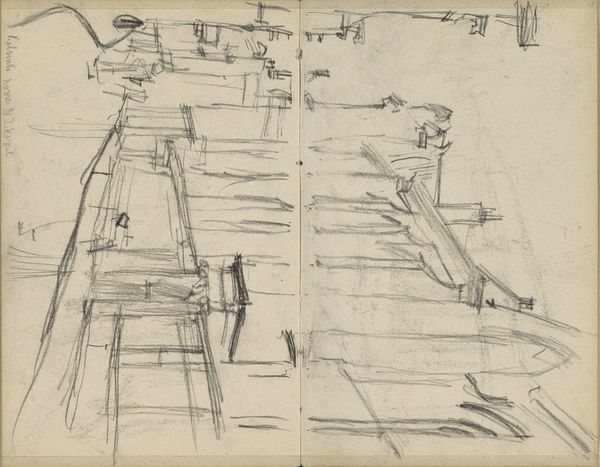

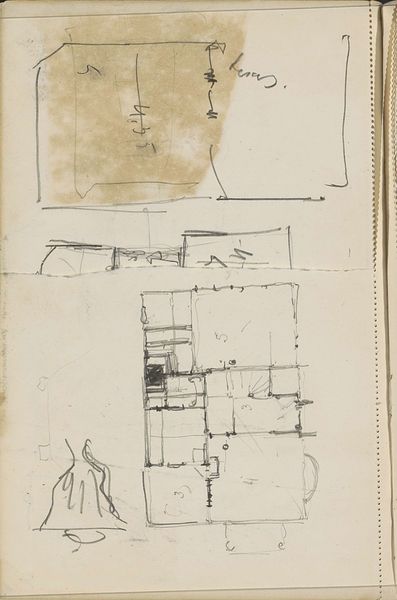

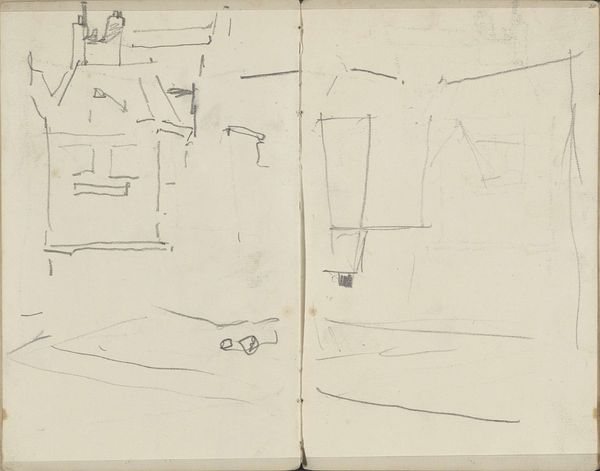

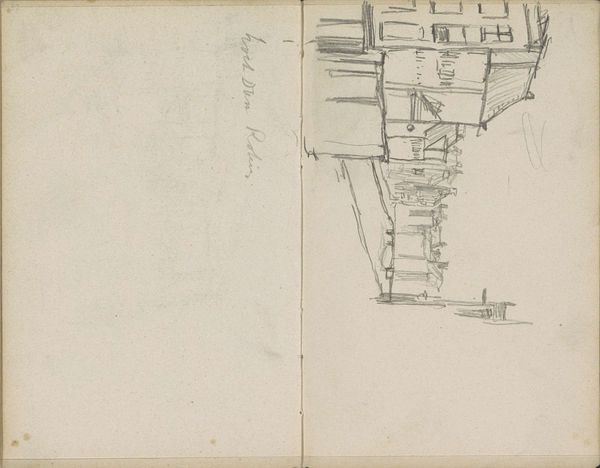

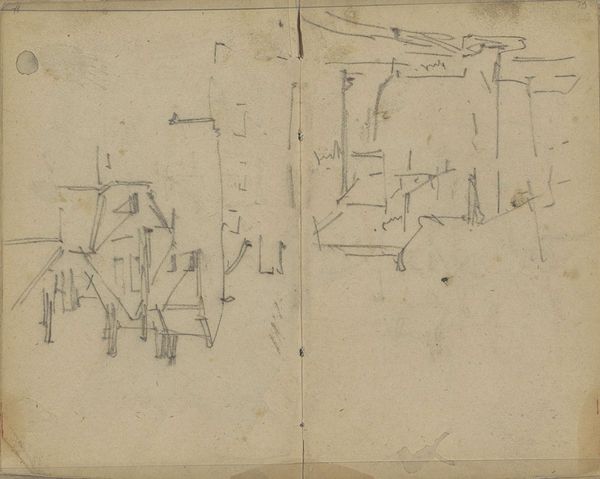

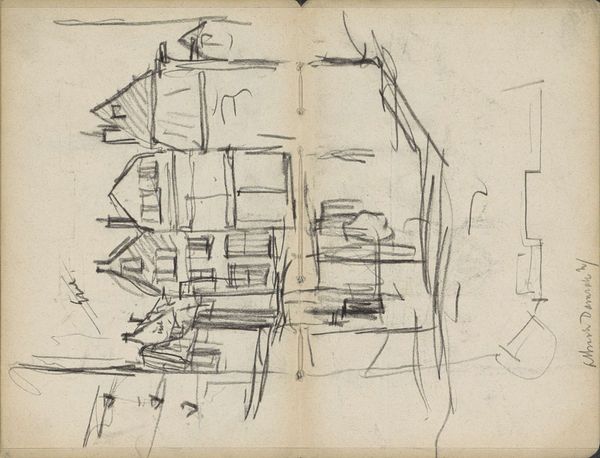

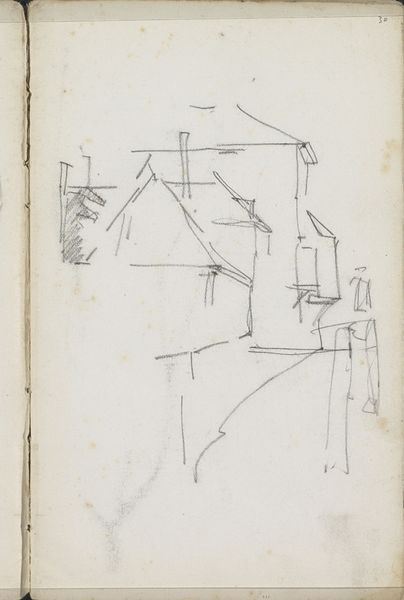

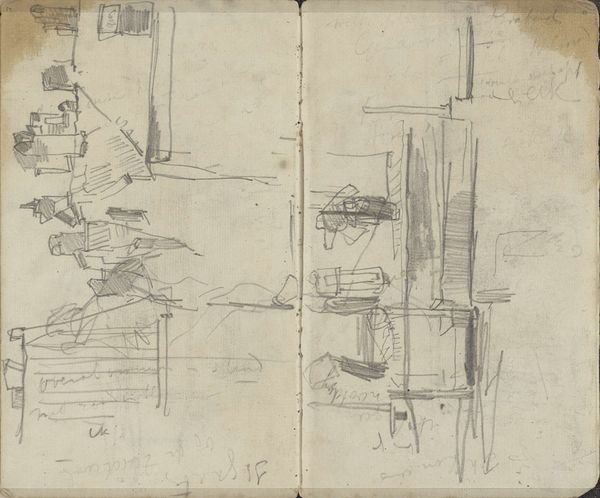

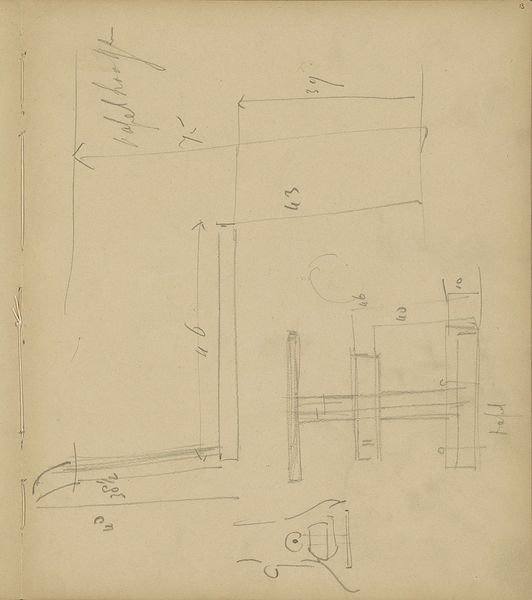

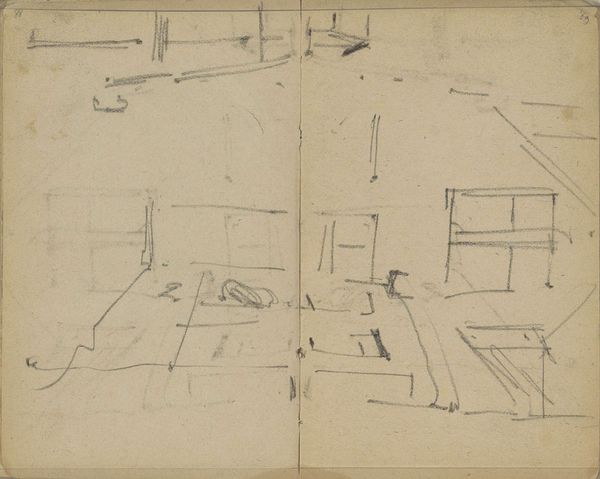

Curator: Here we have a fascinating sketchbook page, “Gezicht in Amsterdam, mogelijk Prinseneiland,” or “View in Amsterdam, possibly Prinseneiland,” dating from around 1906 to 1923, by George Hendrik Breitner. It's a quick cityscape rendered in pencil and ink. What’s your initial reaction to it? Editor: It feels unfinished, raw. Almost like catching a fleeting thought. The buildings seem to emerge and dissolve simultaneously. There’s a real tension between presence and absence. But I’m wondering about Prinseneiland… what's the significance of potentially choosing to depict that place? Curator: Well, if it is indeed Prinseneiland, this area in Amsterdam has a layered history deeply interwoven with the city's maritime past and subsequent urban development. Breitner may have been attracted to it for its representation of evolving socio-economic structures and the narratives embedded within Amsterdam's urban fabric. But to your point of fleeting impressions... Breitner's style, very impressionistic, captured everyday scenes and street life. You see this artistic fascination emerge here, yes? Editor: Definitely. And this sketchbook page feels so immediate. Like he was just trying to capture the light and shadow, the feel of the place. How would you say the quick strokes speak to the urban experience of early 20th century Amsterdam? I find this especially striking because we're in a moment of immense change: politically, culturally. Curator: Exactly, Breitner used a similar sense of movement to render the flow of figures walking across the Dam square, to reveal an interest in the rhythms of the city as such. In this particular page, look at the rapidly sketched architectural elements – windmills, rooftops. These are powerful symbols of Dutch identity. Editor: Absolutely. Windmills in particular carry generations of associations related to economy, and landscape itself. The sketchy nature feels appropriate given the city’s own transience. This makes me think about who Breitner's audience was. Sketchbooks, even when made public, operate at a more intimate level than monumental works of art, right? Curator: True. This lends a sense of intimacy. They give us a direct line to his visual thought process, allowing us to experience Amsterdam through his eyes in a way that feels immediate and personal. Editor: And it encourages us to consider our own impressions, our own fragmented memories of urban spaces. Thanks to this, I notice that this invites a more vulnerable kind of engagement with the viewer, than perhaps what Breitner would've considered in more resolved artworks. Curator: A vulnerable invitation into both process and place… I think that's a wonderful way to describe the impact of this intimate, quick "Gezicht in Amsterdam".

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.