photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 86 mm, width 52 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

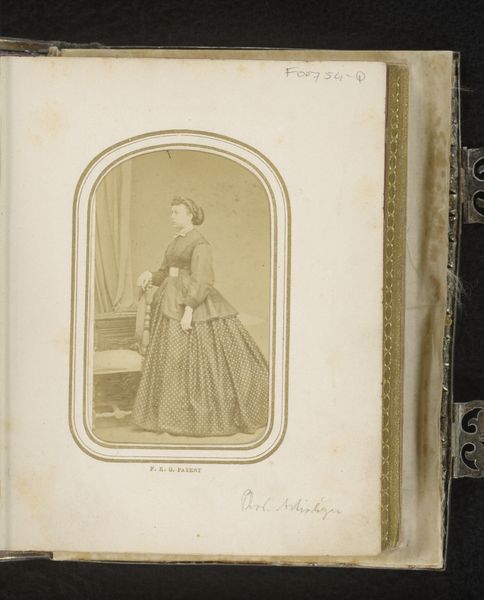

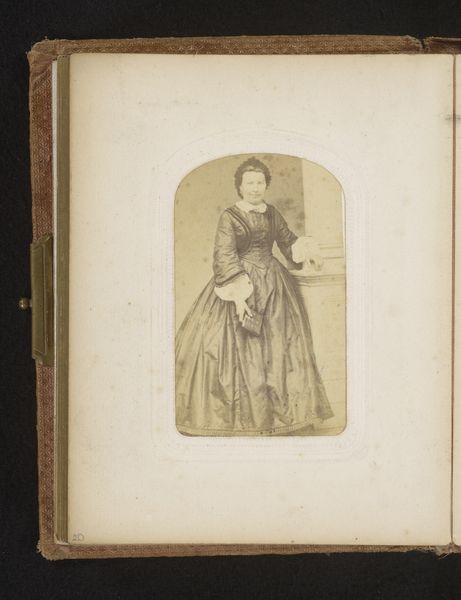

Curator: Looking at this albumen silver print, one immediately notes a somewhat somber atmosphere. The subject, a woman elegantly posed, is captured with a certain gravity. Editor: And presented as “Portret van een vrouw met waaier” – Portrait of a Woman with a Fan. Produced sometime between 1860 and 1880, by V. Vagneur, this piece intrigues me particularly regarding its photographic process, this specific approach in photography production as an industrial activity that became more popular around that time. Curator: The context is definitely crucial. Studio portraiture in the mid-19th century had democratizing effects. While traditionally, portraiture was a domain for the elite and powerful, photographic technologies, gelatin-silver-prints to be precise, made this attainable for the emerging middle class. This allowed people to create and curate their own representation, fashioning identity through posing and presentation. Editor: Exactly. I mean, let's consider what a photograph meant then – an extraordinary object of labor, where light-sensitive materials become image carriers through a complex series of manipulations, fixations, and washes. The photograph here isn't simply an image. It is a social commodity and artifact loaded with meaning through each individual step in its physical development. Curator: I concur. She embodies this emergent power through her attire. What some could define as a modest gown carries weight in its fabric and length. It silently states class, and, through its careful draping, communicates respectability – ideas essential to her perceived role in society. Her subdued countenance further serves to cement this reading. It becomes less a capture of fleeting emotion and more about preserving and displaying an aspirational status. Editor: I find it fascinating how such a small detail—like a prop fan that, admittedly, is barely present—could signal leisure or refinement, adding a layer of consumption and status. It really tells us how commodities themselves were shaping identity in an emerging consumer culture. Curator: It makes you wonder about the individual's aspirations for social mobility and whether photography provided new opportunities for representing this class’ sense of self in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Editor: Precisely. And considering that, through meticulous analysis of the production involved, these seemingly modest images open avenues to discuss larger themes of labor, production, identity construction, and the commodification of images in the nineteenth century. Curator: Looking at the artwork as a whole really showcases how an artifact—created through specific technical processes—can speak volumes on so many layers within its historical context. Editor: Absolutely, the combination of historical awareness and an understanding of materiality invites viewers to question not only what is depicted, but how it became an enduring visual emblem in social history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.