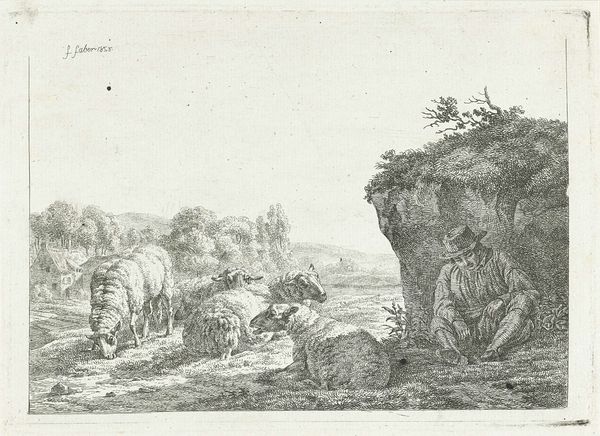

Landscape with Ruins of Statues and Vases 1746

0:00

0:00

drawing, print

#

pen and ink

#

landscape illustration sketch

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

pen drawing

#

head

# print

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

vase

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

pencil work

#

pencil art

Dimensions: Sheet: 7 1/2 × 11 1/16 in. (19.1 × 28.1 cm) Plate (trimmed, inlaid): 4 5/8 × 6 13/16 in. (11.8 × 17.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is "Landscape with Ruins of Statues and Vases," a pen and ink drawing completed in 1746 by Comte de Jacques Laure Breteuil, now residing here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It's a remarkable piece. Editor: Yes, quite evocative. There's a distinct sense of decay, a certain romantic ruin aesthetic that I find very appealing. The level of detail, all those intricate lines creating texture and depth, is quite striking for a pen and ink sketch. Curator: Absolutely. It speaks volumes about 18th-century aristocratic tastes. Breteuil was himself a prominent figure, and works like this reflected his sophisticated understanding of classical forms and the contemporary vogue for picturesque landscapes. The materials themselves—paper and ink—were relatively accessible, but the skill required positioned such drawings as valued commodities. Editor: Precisely, and considering Breteuil's social standing, it's interesting to consider who this work was for. Was it intended for a wider public audience, or was it meant for a private collection, enjoyed within the elite circles he frequented? How did such depictions of classical ruins influence landscape design and the architectural follies being constructed on estates at that time? Curator: I believe it's both a celebration and a critique. The fragmented sculptures, the overgrown vegetation, they point to the inevitable decline of even the greatest empires. But consider also the labor involved— someone had to produce the paper, mix the ink, engrave this scene. The very act of creating such a detailed image highlights the power and skill involved in artistic production, regardless of the melancholic theme. Editor: That is a valid point. I find myself drawn to the political implications, though. Artworks featuring classical ruins become symbols of empire—lost grandeur that reflects on contemporary society and its own aspirations or anxieties related to power. Were there specific socio-political debates that this imagery would have been a part of, in its time? Curator: Undoubtedly, art then, like now, served as a powerful mirror, reflecting anxieties and aspirations. Breteuil was clearly well versed in using art to engage those conversations. Editor: Thank you for those insightful points; I will never look at similar drawings in the same light again. Curator: And thank you! I've also found new connections to explore as well!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.