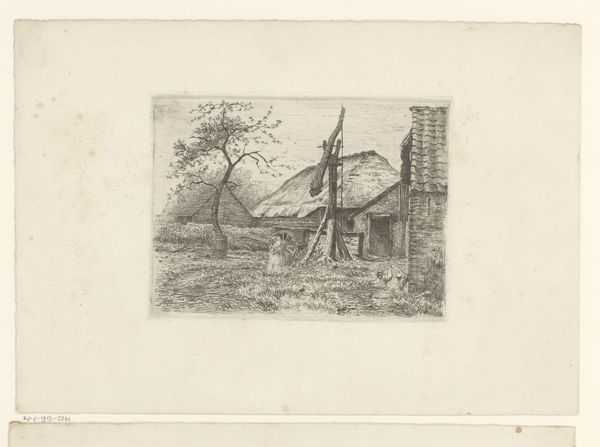

drawing, print, etching, paper

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

paper

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 166 mm, width 213 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

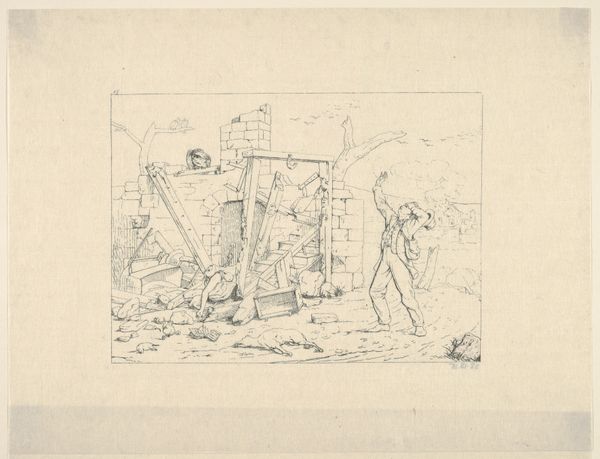

Curator: Here we have "Boerenerf met duiventil," which translates to "Farmyard with Dovecote," an etching and print on paper made after 1635, attributed to Frederick Bloemaert. It's part of the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: It has the air of a fleeting dream…a little melancholic maybe? The delicate lines remind me of early morning mist hanging over fields. The scene seems simple but also strangely burdened. Curator: Burdens? Well, think about what a farmyard meant. The etching presents a working landscape. The dove cote—raised to protect against predators—required labor to build, harvest, and maintain. It's all about structures! Even the human figures in the background…fixing the fence… Editor: Ah, that's what's creating the somber feeling, it's the unrelenting nature of human intervention. You know, the repetitive, often unacknowledged efforts shaping our environment. The dove cote looks fragile, like it might be consumed by nature again at any minute. The roof on the farmhouse isn't in great condition either! Curator: It’s a study in resourcefulness. The very materials are of the place. It also evokes this tension that emerges in the Golden Age – the creation of a prosperous, well-organized society coming face to face with inevitable material limitations and social constraints of 17th century life. Bloemaert shows how prosperity comes out of human persistence, that drive to control chaos. Editor: That's it. And Bloemaert’s mastery lies in showing it subtly. The way he captures the textures – rough wood against soft sky, the density of labor and fragile structure all at once is exquisite. I love the lone animal by the house. It’s a nice, very quiet observation of everyday toil. Curator: I find myself returning to the composition. It appears straightforward, but it uses that delicate, precise rendering of labor to create that atmosphere…of human existence trying to create stability and control on very impermanent ground. Editor: Well, I will certainly view farmyards with fresh eyes from now on – as potential portraits of struggle and silent creation! Thank you, Frederick.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.