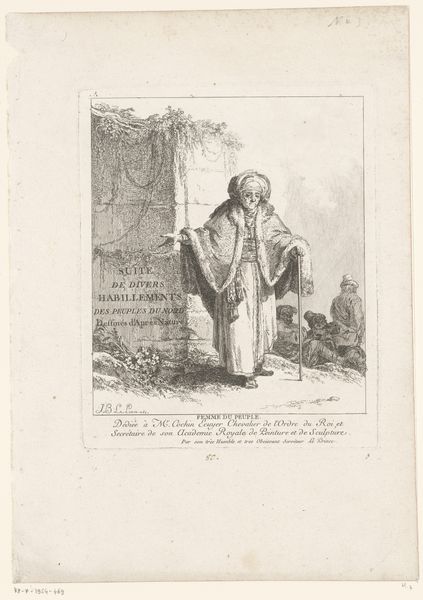

Dimensions: height 146 mm, width 99 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a print titled "Oude Moskovische vrouw met stok in een korte mantel," or "Old Muscovite Woman with a Stick in a Short Cloak." Jean Baptist Leprince created it in 1764. It's currently part of the Rijksmuseum's collection. Editor: Immediately, the texture strikes me. The crispness of the engraving gives an incredible dimensionality to what appears to be luxurious fur trim. It’s amazing how Leprince evokes such richness with line alone. Curator: Indeed. Consider the historical context; prints like these disseminated visual information across Europe, often shaping perceptions of different cultures and social strata. It would be so valuable to investigate more precisely which community or intersection of Moscow society is captured here. Does this portrait flatten the culture into only one point of view? Editor: That brings up the materiality. Engravings, being reproducible, served a specific social purpose. They made imagery accessible. Were they truly 'accessible' in the 18th century or were they restricted by purchasing power, feeding into certain hierarchies despite appearing to democratize visual culture? And thinking about that fur trim... what does that say about the economic realities and exploitation surrounding such materials? Curator: Absolutely, these objects are so layered with these complicated perspectives! I find myself wondering who she was, this woman. There’s a power dynamic, too. She is being viewed; she is an object. Is she participating in her portrayal, or is she subject to the gaze of Western Europe, especially given her perceived status, potentially, as ‘other?' I wonder how her race and age factor into the audience's perception of her, too. Editor: Precisely. The print itself, created through labor-intensive processes, speaks to both the artistry and the industrial elements present. Copper plate, ink, paper... and all the skilled hands involved. Leprince transforms common materials to illustrate a commentary of society, both that of the sitter and his immediate context. Curator: Thinking about the woman herself, her attire, including the fur and the head covering, speaks volumes. I want to dive deeper to decode the social codes, the meanings attached to those materials at that moment, what identities they signify. Editor: Ultimately, examining this seemingly simple engraving invites us to think about materiality, labor, and dissemination in the 18th century—concepts still utterly relevant today. Curator: Yes, and to confront the often fraught relationship between representation and power, and how the circulation of images shapes, and sometimes distorts, our understanding of others.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.