drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

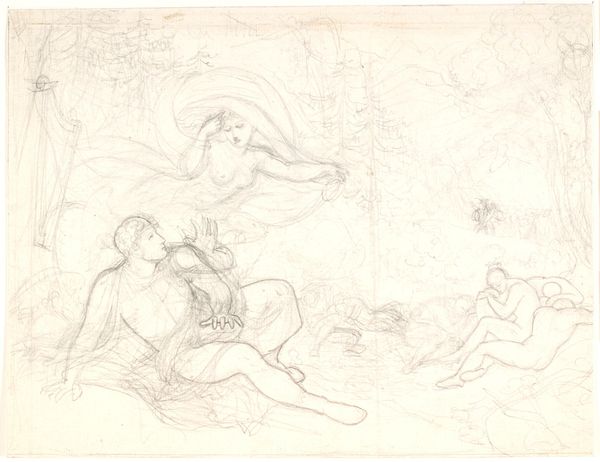

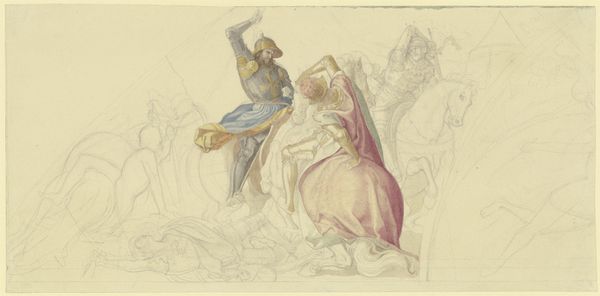

Curator: This is Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres' "Venus Hurt by Diomedes," created in 1844. It’s a pencil drawing showcasing his incredible draftsmanship. Editor: It has an unfinished quality, almost ethereal, with faint lines defining figures emerging from the ground, as if barely present. The color adds to that sensation. It’s so subtle; are those tones even gray or shades of light blue? Curator: The scene depicts an episode from the Iliad. Diomedes wounds Venus, who is being assisted by Iris. The entire drawing embodies Ingres' neoclassical ideals, harking back to classical Greek and Roman art in both style and subject matter. The precision is extraordinary; observe how Ingres meticulously delineates each figure. The artist’s masterful use of line and form is on full display. Editor: Absolutely. The figures are idealized, with that sort of cool, detached emotional quality you often find in Neoclassical works. Yet, what does it say about 19th-century academic art when a male hero wounds the goddess of love? I’d be curious about how that intersects with changing gender roles during this era. How did the Parisian public respond to its seemingly sanitized violence toward a female deity? Curator: Such inquiries into contemporary perspectives remain valuable. The drawing reflects the prevailing academic tastes and classical learning that Ingres so valued. We mustn’t ignore his position in the French Academy. Editor: But isn't the academy always negotiating existing systems? I see it more as a commentary on power and the inherent violence in those traditional power structures, thinly veiled in this classical scene. Curator: Violence exists for sure. Yet, in many ways the French Academy system afforded female artists the institutional backing they would have struggled to attain on their own. I wonder, however, how much Ingres’ approach might have differed had he considered the violence to other marginalized peoples within France. Editor: Fair point. I'd still like to interrogate this narrative from a feminist perspective, specifically considering the pervasive historical marginalization of women, and how even a goddess isn’t exempt from male violence within certain sanctioned narratives. Curator: I appreciate you bringing those contemporary interpretations into conversation with the artwork. It invites our visitors to make those critical connections themselves. Editor: Precisely, because viewing it strictly through the lens of Neoclassicism limits our understanding, doesn’t it? Thank you, by the way, for introducing us to this under-known treasure in the museum's collection.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.