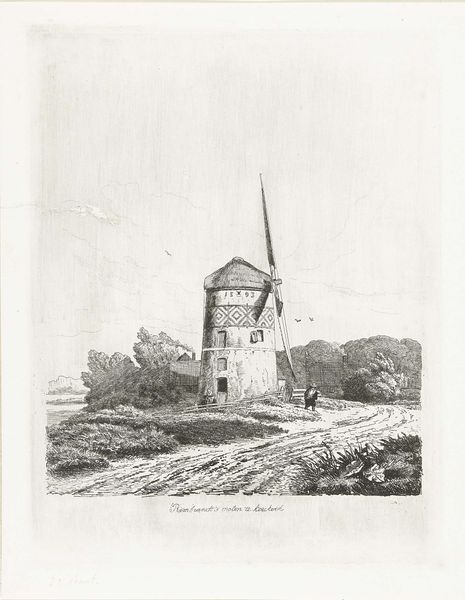

print, etching, engraving

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

etching

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

archive photography

#

historical photography

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 295 mm, width 225 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

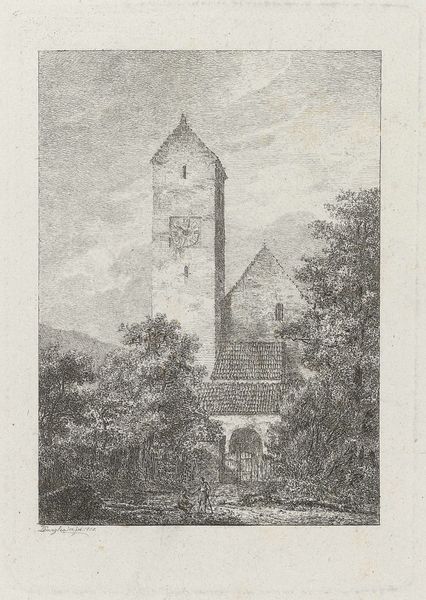

Curator: This etching, titled "Seintoren te Nijemirdum," made between 1822 and 1845 by an anonymous artist, offers a glimpse into the Netherlands of the early 19th century and is held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It has such a quiet feel to it. The neutral tones really emphasize the imposing architecture and the open landscape. You can sense the history embedded in that tower. Curator: The work is particularly compelling when you think about the history it documents. The stark monumentality of the tower becomes this symbol of power, permanence—but against the backdrop of daily life with people casually walking by. The history embedded in this rural scene becomes part of a larger social narrative about national identity. Editor: The materials are so crucial to understanding this piece as well. This anonymous printmaker carefully used etching and engraving to reproduce precise architectural details. Think about the skilled labor required to render those stones, those tiny human figures…The consumption of images like this also fed into a broader industry. Curator: And doesn't that consumption then reinforce specific ways of seeing landscape, culture, and ultimately, power structures within Dutch society at that time? Who benefits from promoting such views of permanence and stoicism? I always try to bring discussions about the context surrounding national identity into a contemporary view of diversity and multiculturalism. Editor: Absolutely, the materials and means of production aren’t neutral. But I also want to highlight the artistic labour to consider a wide array of approaches beyond high art. This historical scene comes to us through the hands of real artisans who worked with intaglio processes in potentially collaborative environments. Curator: Seeing the artisan and also acknowledging that these supposedly simple rural scenes, they carry complex cultural codes and promote particular ideological meanings, don't you agree? Editor: Undeniably, considering labor helps unveil those codes that speak to power dynamics and the historical context of art and image making in nineteenth century Europe. Curator: Examining images such as this pushes me to consider broader sociopolitical impact—connecting history and contemporary society to ask critical questions of our inherited cultural material. Editor: Indeed, through material consideration, we start unpacking the networks that these images sustain; we understand both artistic craft and consumer economies that built shared visions of place and nationhood.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.