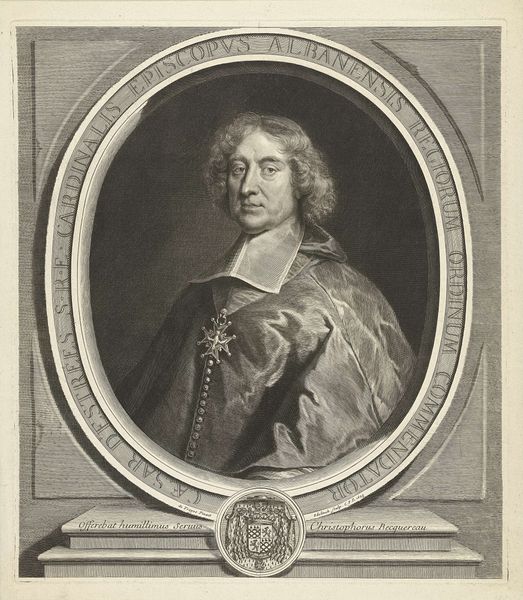

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 279 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this, the somber yet dignified presence conveyed by Antoine d'Aumont de Rochbaron jumps out immediately. There's a calculated gravity that the artist has etched onto his features. Editor: Precisely! This print, created in 1649 by Johannes (II) Valdor, captures d'Aumont within the established visual rhetoric of power, a reflection of his station. Note how Valdor has encased him in a rather ornate, decorative setting. It tells us much about portraiture and status in the baroque period. Curator: That ornate framework certainly makes a statement. I can’t help but notice the almost surreal, and frankly, somewhat sexualized female figures flanking the portrait. They speak volumes about the era’s complex understanding—and exploitation—of the female form, even in seemingly unrelated contexts such as a nobleman's portrait. It almost feels like a hyper-masculine response. Editor: It’s certainly busy! But that level of ornamentation, those symbolic flourishes, weren't accidental. The framing reinforces social hierarchies. D'Aumont's own military achievements and aristocratic lineage would be central to how viewers at the time would have understood this work. Those figures function as allegorical references – potentially Fame and Abundance given the cornucopias! Curator: Right, you are leading me towards viewing them as emblems within the elaborate tapestry of power Valdor is weaving here. They subtly yet powerfully remind us of the socio-economic landscape. In a portrait intended to secure a legacy, everything, even ornament, is ultimately a statement. The work becomes not merely about capturing likeness but actively constructing an image, which certainly reflects contemporary power structures in regards to wealth, legacy and position. Editor: Indeed. Ultimately, viewing the work through this socio-historical lens enables us to engage critically not only with the image itself, but also with the structures and attitudes it perpetuates. The portrait becomes more than an object; it becomes a conduit through which the past speaks, sometimes unsettlingly, to our present. Curator: I appreciate your detailing of the context behind portraiture's power, bringing attention to those historical elements which help us view d’Aumont’s image with greater historical perspective. It does invite us to recognize just how much art and legacy, even print-making such as this engraving, can impact perception. Editor: It has been insightful to analyze the historical significance within its era of creation; aspects that certainly enrich any museum visit!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.