#

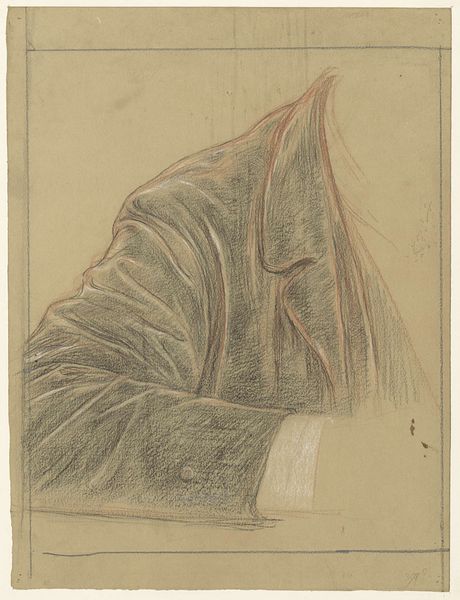

pencil drawn

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

#

sketchbook art

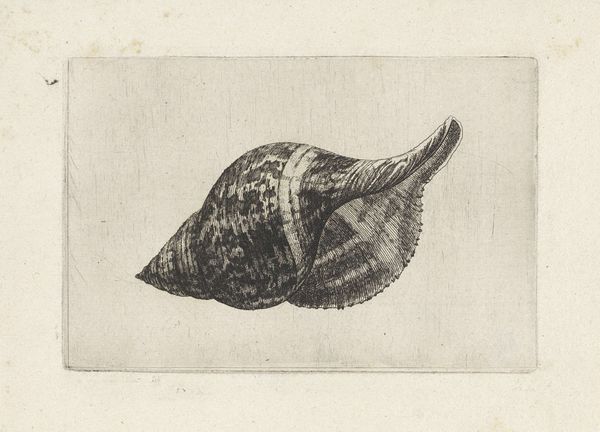

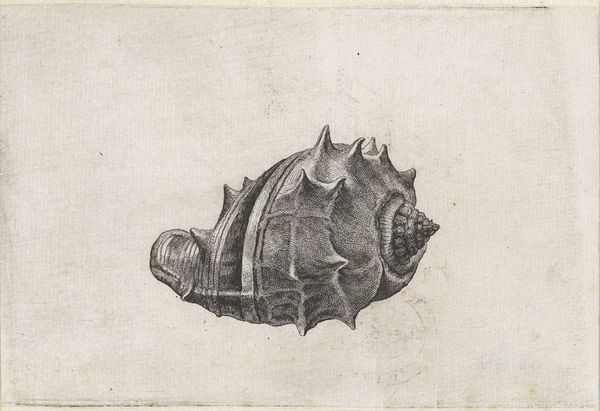

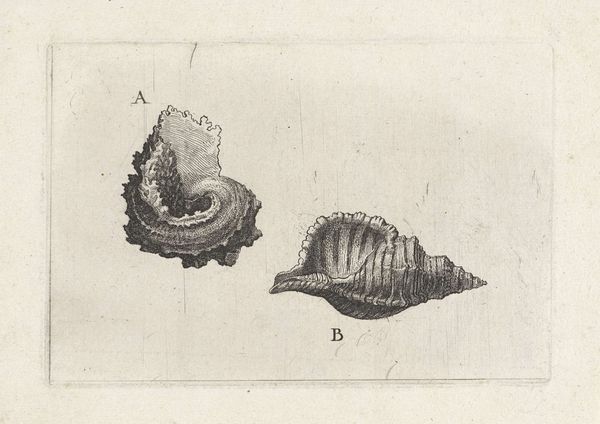

Dimensions: height 94 mm, width 139 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is "Schelp, pleuroploca trapezium" by Wenceslaus Hollar, dating from 1644 to 1652. It’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum. It appears to be a detailed sketch of a seashell. I’m struck by the precision of the lines – it feels almost scientific in its approach. What do you see in this piece, especially considering its historical context? Curator: What immediately grabs me is the act of observation itself. Hollar, living in a period defined by colonialism and expanding global trade, meticulously depicts a seashell – an object intrinsically linked to those power structures. How might this image speak to early forms of scientific cataloging and the appropriation of nature that underpinned empire? Editor: That's interesting! I hadn’t considered the colonial aspect so directly. I was more focused on the artistry of the rendering. Curator: Exactly, we often separate the aesthetic from the political, when these spheres are constantly informing each other. What kind of value would a shell have for someone during this era, a period of immense exploration? Was it just aesthetic? Or did it hold more complex significations, relating to global power dynamics and the control of natural resources? Editor: So, looking at the detail then becomes a kind of… dissection of power? Almost like studying a map of colonial influence, encoded in a shell. Curator: Precisely. The shell transcends its form as a simple object to represent a system of control, a representation of early forms of capitalism as it relates to both Europe and other countries during this era. Hollar's work gives us a peek into the complexities that come with understanding natural history and trade in the 17th century. Editor: I never would have thought of it that way just looking at it. Thank you, that gives me so much to consider. Curator: The beauty of art history is exactly this potential to reveal social history through these types of creative records.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.