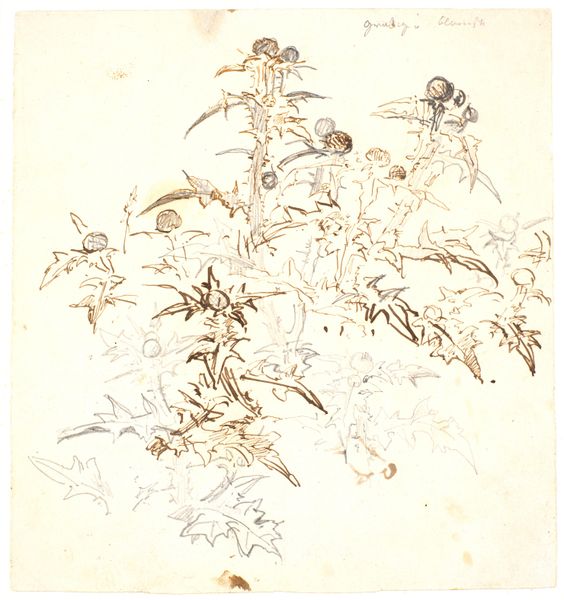

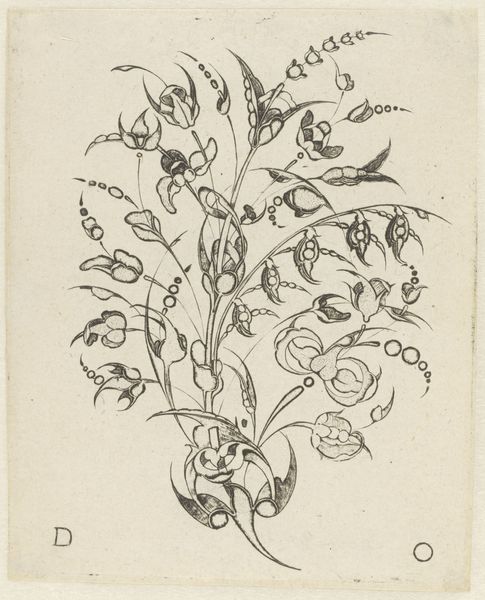

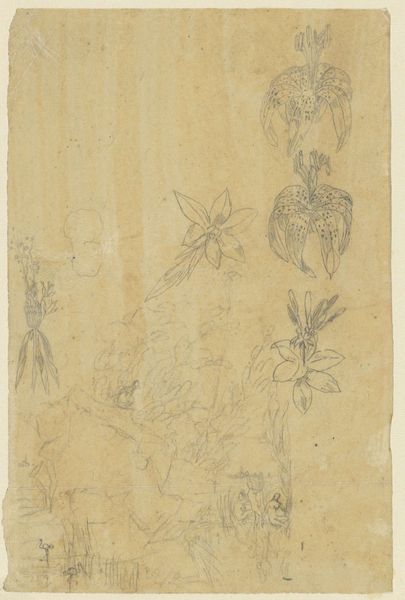

drawing, ink, pen

#

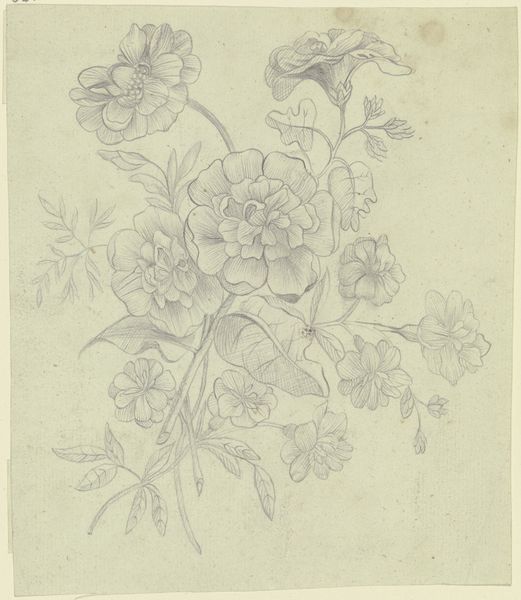

drawing

#

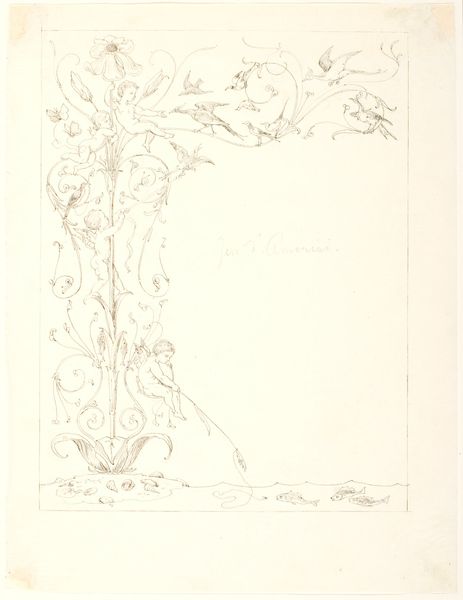

ink drawing

#

pen sketch

#

landscape

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

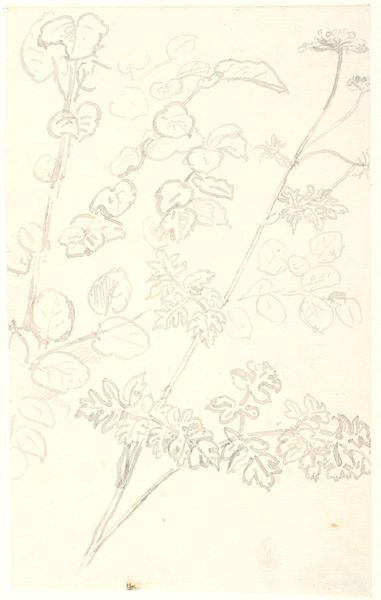

botanical drawing

#

pen

Dimensions: 292 mm (height) x 175 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: Let’s spend a moment contemplating this pen and ink drawing entitled “Plantestudier”, or “Plant Studies”, created by Dankvart Dreyer in the 1840s. What strikes you immediately? Editor: It feels delicate, almost tentative, like a whispered secret from the garden. The brown ink on the aged paper gives it a fragile, ephemeral quality. It’s beautiful in its simplicity, really. Curator: Indeed. Dreyer’s choice of medium, the immediacy of pen and ink, is crucial here. This wasn't meant as a finished piece, but more as a study, an exercise. Consider the labor involved; each line carefully rendered, a direct translation of observation. We see the artist’s hand so clearly in the rapid hatching, the varying line weights... Editor: Yes, it’s as if I’m right there with him, peering over his shoulder as he sketches, capturing the light filtering through the leaves. The economy of line is astounding—he manages to suggest form and texture with such minimal marks. I wonder what he was thinking, feeling, as he focused on these tiny botanical details. Curator: It also points to the rising interest in naturalism in Danish art during this period. But remember, this wasn't detached scientific documentation. Look closer—Dreyer imbues the plants with a kind of quiet grandeur, elevating them beyond mere specimens. These aren’t just leaves, but characters in a drama of nature. Think about the paper too—its sourcing, its cost. Not everyone had access to materials like this. Editor: I can’t help but think about his dedication; he notices beauty in such seemingly unremarkable things. In today's world, with our phones, it can be harder to pay quiet attention. Curator: Precisely. So, while the work speaks of scientific interest in the landscape, it does so in a way that embodies the aesthetic principles and values of the Romantic era. And beyond its aesthetic or historical significance, you feel that commitment. Editor: Right, and maybe that's why it still resonates— a pure expression of the artist’s presence in the natural world. Curator: Agreed. A potent reminder that careful looking is, in itself, an act of creation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.