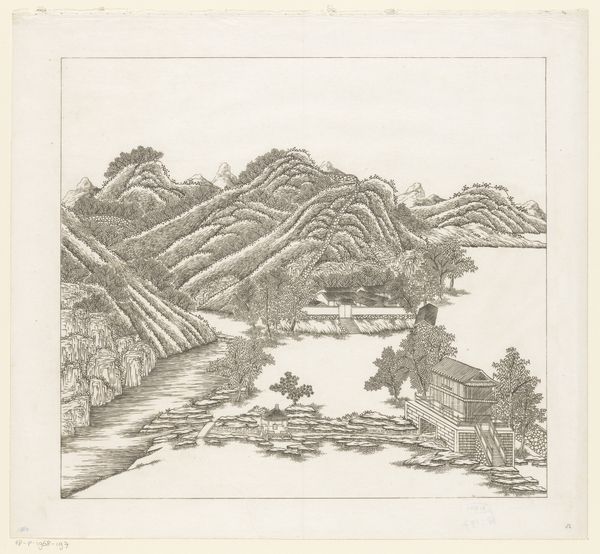

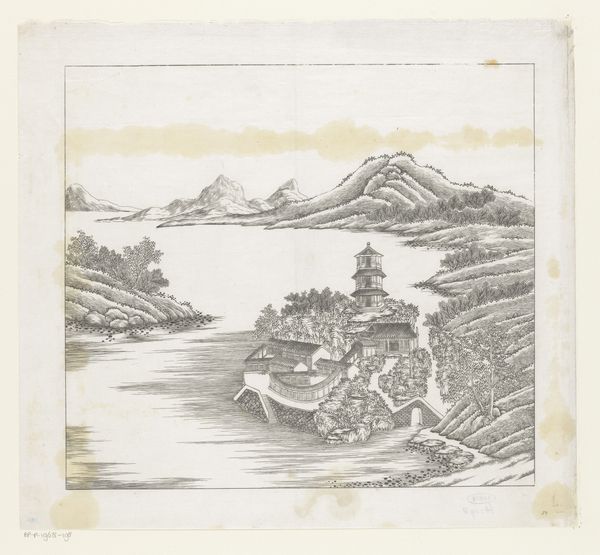

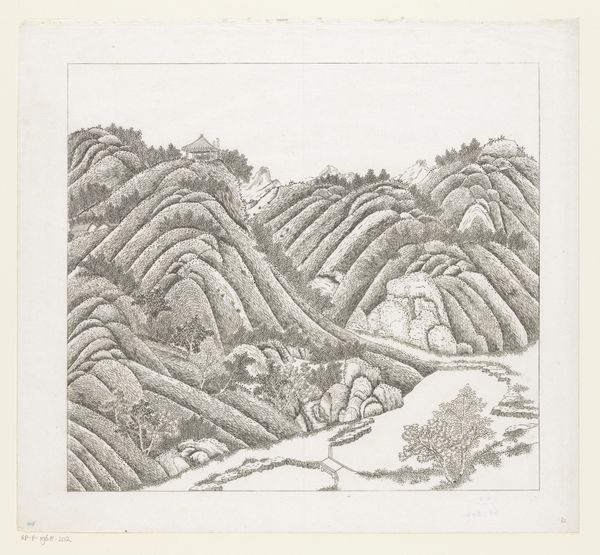

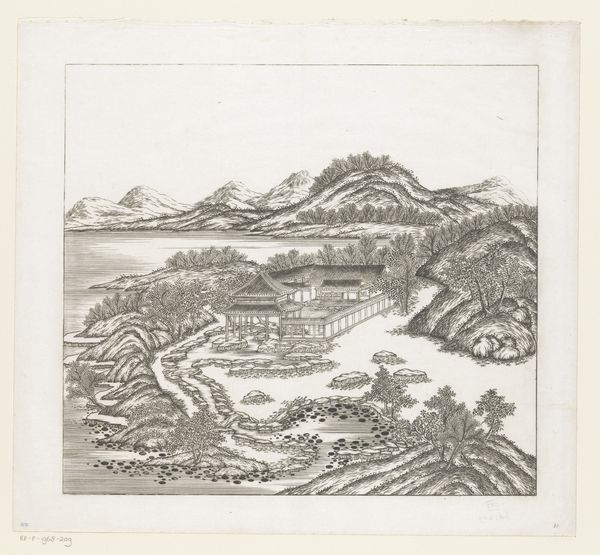

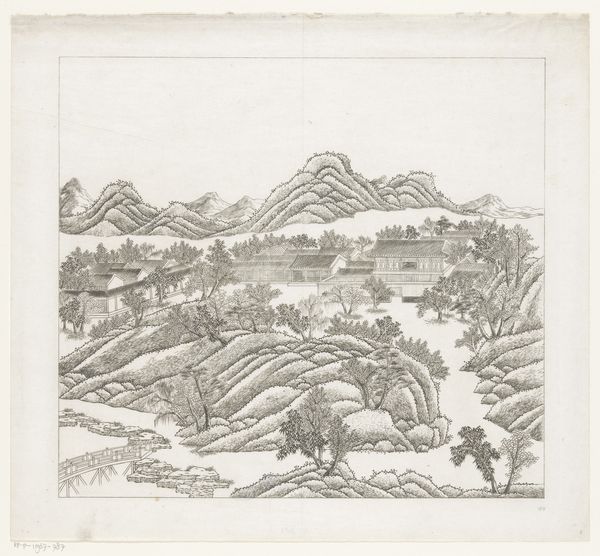

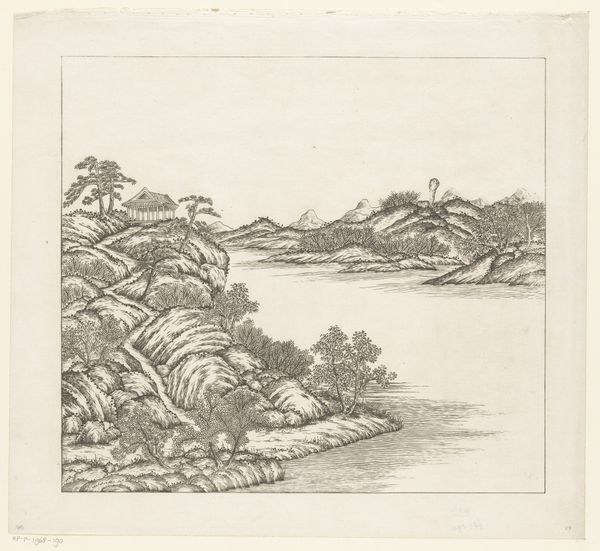

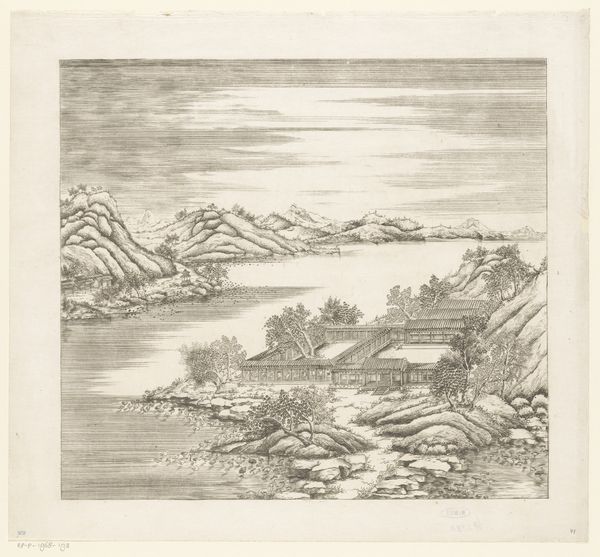

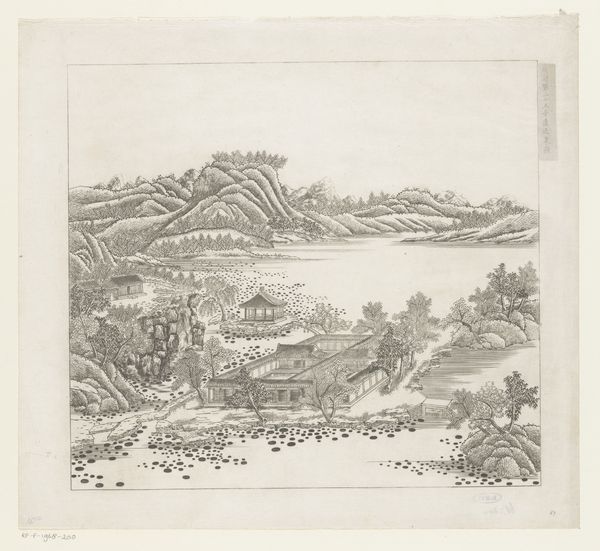

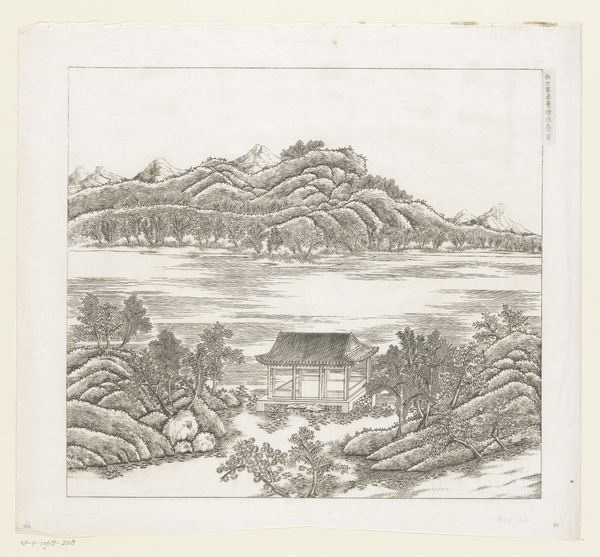

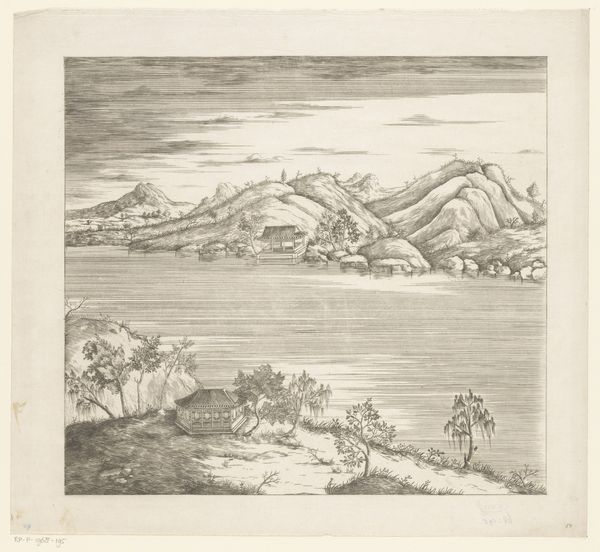

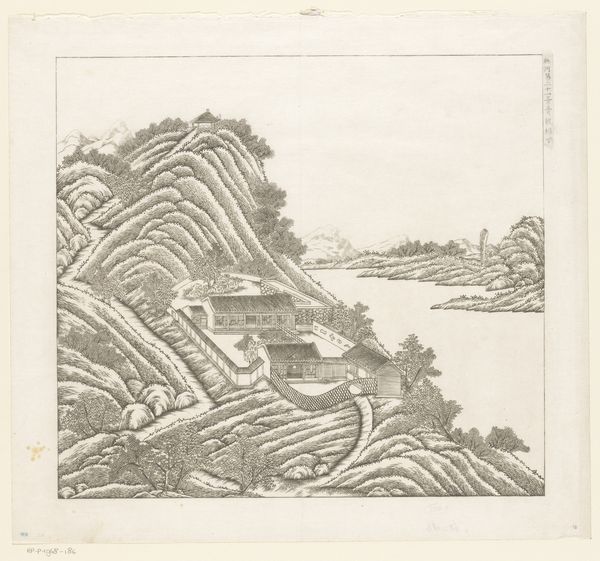

Gezicht op een deel van het keizerlijk zomerpaleis in Chengde (Jehol) te China 1712 - 1714

0:00

0:00

matteoripa

Rijksmuseum

drawing, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

light pencil work

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

asian-art

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

geometric

#

pen-ink sketch

#

line

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 325 mm, width 356 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a drawing by Matteo Ripa, entitled "View of part of the Imperial Summer Palace in Chengde (Jehol) in China," created sometime between 1712 and 1714. Editor: My first impression is how meticulously detailed and serene this landscape appears, despite being rendered with such simple lines. There’s a real sense of order, even a kind of constrained beauty. Curator: Yes, the precision is striking. As an engraving, it represents a very specific and considered method of conveying both information and, perhaps, a sense of the 'other'. Remember, Ripa was an Italian missionary. The rendering of the palace and the land surrounding it might reflect an effort to categorize and communicate what he was witnessing in China back to a European audience. Editor: Exactly. It's essential to consider the power dynamics at play when viewing art produced within colonial or cross-cultural contexts. The "Imperial Summer Palace" itself, meant for leisure, governance, and ritual performance, appears flattened here, reduced almost to a scenic backdrop. What power did Ripa possess in depicting and disseminating the representation of the Chinese royal enclave for European audiences? Curator: That's a great point, though perhaps not the entirety of the picture. What of Ripa’s awe at the ingenuity of Chinese landscaping, or the symbolism inherent in specific architectural elements? The palace's very location was a calculated claim of power and divine right, wasn't it? Editor: Agreed. We need to question how this representation could contribute to the exoticization of Chinese culture and its rulers. Whose gaze is truly served? The reduction of a cultural institution can easily lead to a misrepresentation or oversimplification of Chinese dynastic and governmental practices of the Qing Dynasty, thus perpetuating stereotypes. Curator: But symbols transcend cultural barriers; they serve as cultural memory through shared meaning. In some ways the rendering, itself, honors the permanence of what is pictured. Look, for instance, at the way the river winds, anchoring the whole scene… It seems Ripa was, at least in part, awed by what he witnessed. Editor: I don't deny that an aesthetic exchange may have been taking place, but such encounters always entail power dynamics that might be easily overlooked. What does the piece tell us about Ripa's views, the Qing dynasty’s relationship with Europeans, and cross-cultural interpretation itself? Curator: Ultimately, art becomes a cultural repository, both celebrating ingenuity and becoming a vehicle for analysis across centuries. Thank you for those vital insights. Editor: And thank you. Keeping an eye on the broader implications and significance behind such work—it is through pieces such as these that one might continue questioning perceptions of gender, culture, race, class, ability, and other factors.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.