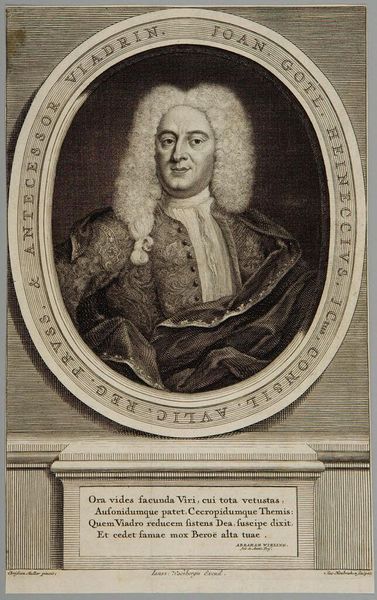

painting, oil-paint, canvas

#

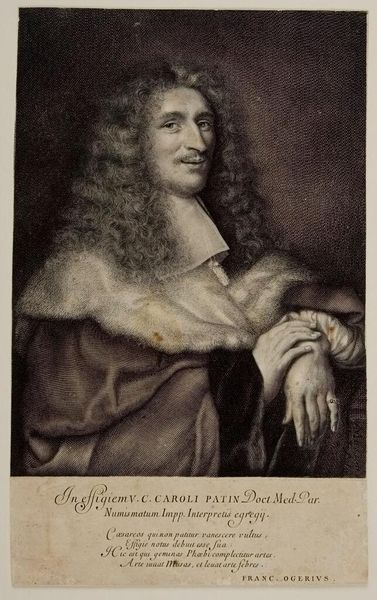

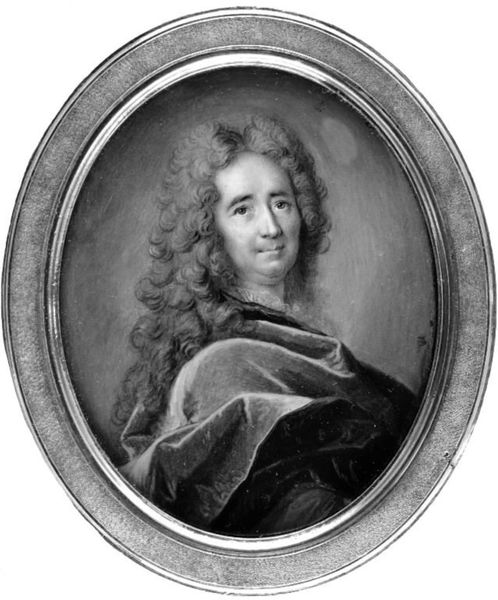

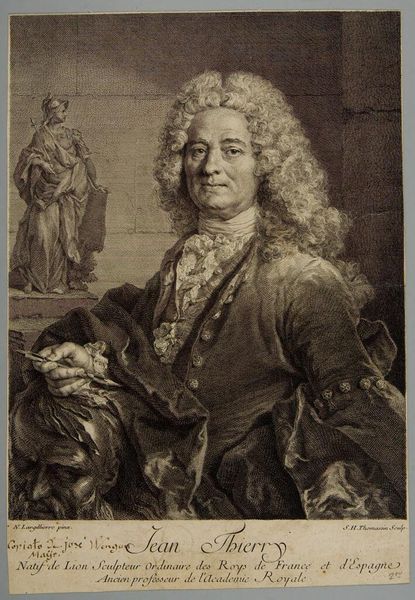

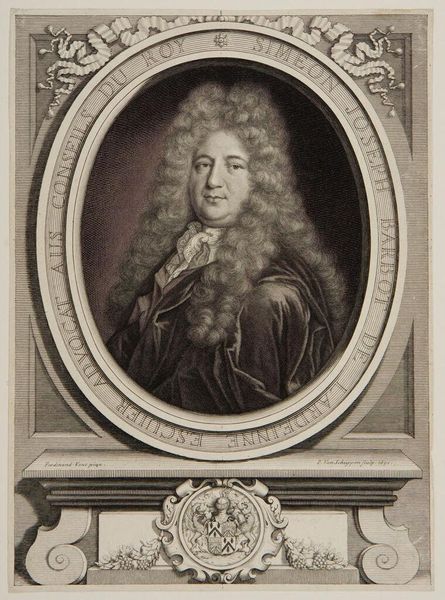

portrait

#

baroque

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

canvas

#

black and white

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 137 cm (height) x 104 cm (width) (Netto), 154.5 cm (height) x 121 cm (width) x 9.5 cm (depth) (Brutto)

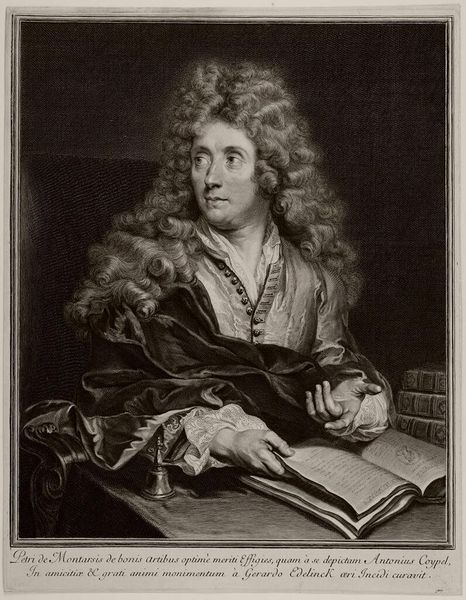

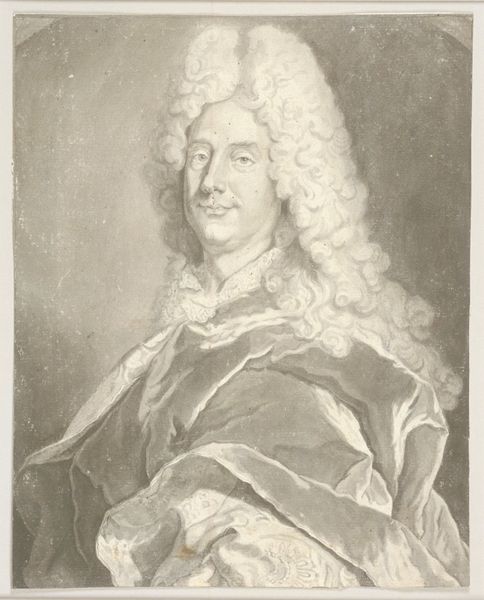

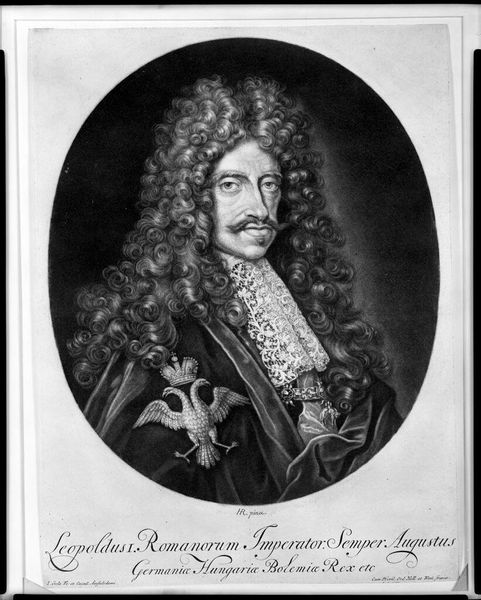

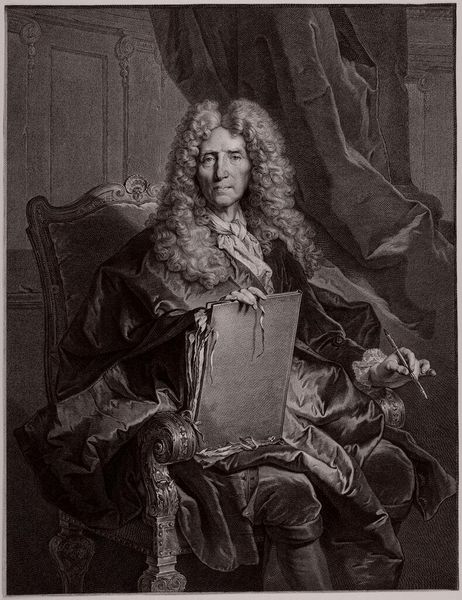

Curator: Oh, my first impression is that this chap is relaxed...almost unsettlingly so, amidst the grandeur. He looks as comfortable as a cat by a fireplace. Editor: Indeed! What you are observing is Hyacinthe Rigaud's "Portrait of High Court Judge Peder Benzon Mylius," crafted in 1721. The medium is oil on canvas, typical of Baroque portraiture, now residing here at the SMK. Rigaud masterfully captures the essence of power and status of a man from the 18th century elite. Curator: Power and status alright! Look at that wig! I wonder if he woke up like that? But there's also something so human... like he’s paused for a moment amidst official duties, a bit world-weary. Do you think that's intended or just my romantic reading? Editor: Your interpretation is quite valid. This artwork reflects the prevailing ideology of its time, where appearances mattered enormously, particularly for men of stature like Mylius. He occupies a meticulously designed setting, enhanced by the careful placement of objects, designed to showcase the wealth and refined taste that legitimized his socio-political status. His direct, though somber, gaze asserts control and demands respect, aligning with Baroque aesthetics that served as potent instruments for affirming elite authority. Curator: Instruments of authority. I like that. There's a performative aspect, almost theatrical, to the way he holds that drape…a kind of studied casualness. It doesn't quite convince, does it? It makes me wonder about all the layers of what wasn’t being shown. I always wonder that about history—all the messy stuff hidden just beyond the frame. Editor: Exactly. This artwork's setting—his library and wardrobe, for instance—serve not merely as decoration, but actively project authority and prestige, creating what Foucault might term a 'scopic regime.' So by positioning his patron within a space filled with recognizable indicators of social rank and educational attainment, Rigaud doesn’t simply represent Mylius; rather, he entrenches a very specific and carefully built representation that reinforces established socio-political conventions and class structures. It calls into question which codes and visual clues support oppressive norms. Curator: Codes and clues for an older game that might be playing out even now. Though hopefully we are writing our own codes in our current chapter. Editor: Yes, though understanding these older visual and societal mechanisms is often essential for unraveling their continued influences and rewriting the outdated power dynamics we’ve inherited today. Curator: A worthy charge! This canvas—not just an object from the past but a conversation with the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.