Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

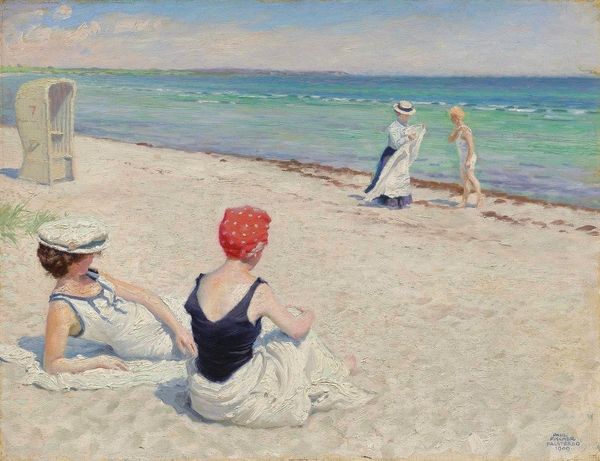

Editor: Monet's "Camille on the Beach in Trouville," from 1870, is an oil painting that gives a real sense of being there on that day. There's something immediate about it, especially in how he's captured the light on her dress and the waves. How do you read this piece? Curator: What strikes me is how the materiality of the paint itself contributes to the subject matter. Look at the visible brushstrokes – how they render not just form, but also texture and atmosphere. The dress isn't just *painted* white; it's *made* of thick impasto suggesting the heavy, luxurious fabrics favored by the bourgeoisie at the time. This contrasts with the more fluid, looser rendering of the sea, reflecting a societal contrast between stability and nature, consumption, and production of leisure time. Editor: So you're saying the way Monet applies the paint becomes part of the social commentary? The thick paint of the dress is related to ideas of bourgeois leisure? Curator: Precisely. The labor of the painter is literally embedded within the paint. Furthermore, consider the *plein air* approach, a then relatively recent development. This work isn't crafted in a studio; it’s capturing a moment, an encounter with a specific place and time. It’s inherently about the *process* of seeing and recording, influenced by the increasing availability of transportable paints and a culture shifting towards outdoor leisure. What is the commodity in *plein air* paintings like this, the finished work or the fleeting instant in the scene, caught by the painter? Editor: That’s a fascinating connection I hadn't considered – linking artistic process, social class, and the materials themselves. I will never look at Impressionism in the same way! Curator: The means of production reveals the message in unique and important ways! Thanks for your insights.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.