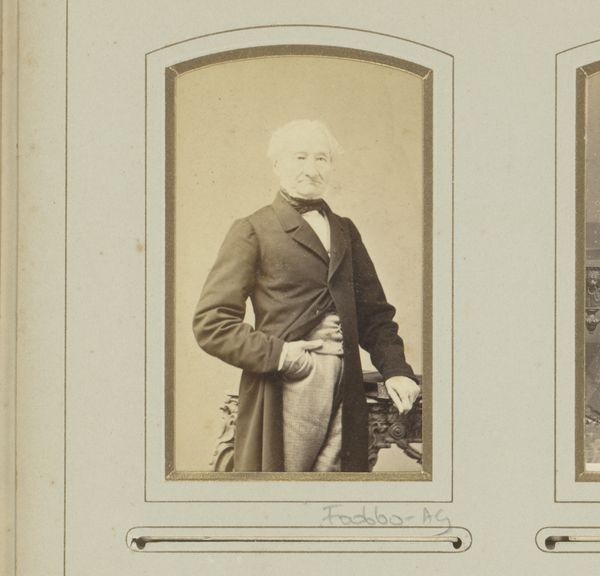

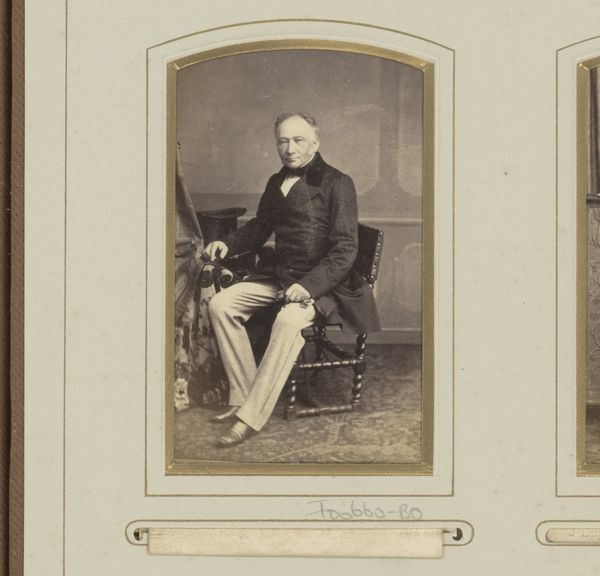

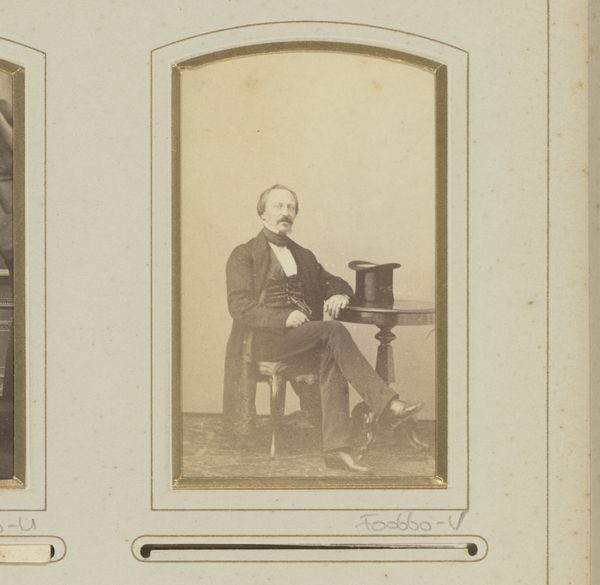

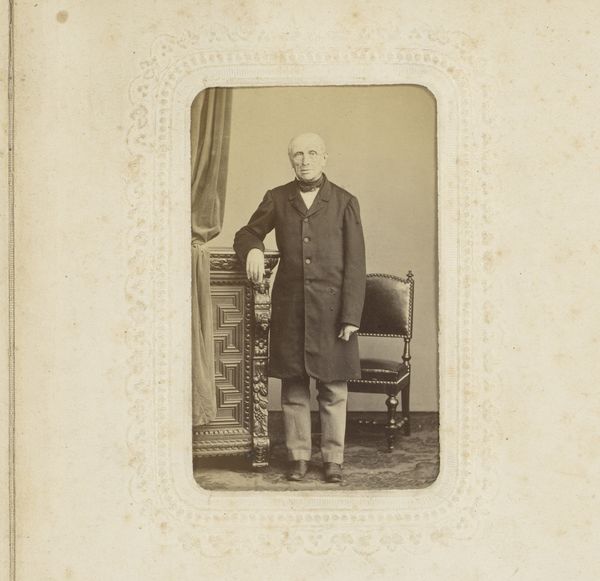

Portret van een staande man bij een tafel waarop een boek ligt 1859 - 1874

0:00

0:00

daguerreotype, photography

#

beige

#

portrait

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

16_19th-century

#

vintage

#

photo restoration

#

book

#

daguerreotype

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

brown and beige

#

old-timey

#

19th century

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This daguerreotype, "Portret van een staande man bij een tafel waarop een boek ligt" from between 1859 and 1874, by Jules Géruzet, has such a stillness to it. You can almost feel the weight of time. What do you see in this piece? Curator: As a materialist, I find myself drawn to the production of the image itself. Think about the resources needed to produce a daguerreotype. The silver-plated copper, the mercury fumes… these were toxic processes undertaken by skilled laborers. It was a deliberate, alchemical transformation of materials. Editor: I never considered it that way, thinking of the labor involved and potential health risks. Curator: Exactly! This isn’t just a pretty portrait, it’s a record of a specific, industrialized process. How did such processes transform the consumption of images by the 19th-century middle class? Editor: Photography democratized portraiture, previously exclusive to the wealthy through painted portraits, thus changing social relationships. Now, you did not need to own vast amount of land to get yourself depicted, what changed was the work for a photo, since standing so still for such photos was also considered labor. Curator: Precisely. We can also examine the context of the sitter. His clothing, the book – all these elements speak to a particular social standing and aspiration, things that come with certain means. This daguerreotype tells a broader story about labor, class, and consumption. Editor: That's a whole different way of appreciating a photo. Thanks, I'm leaving with a new perspective, and thinking of what happened beyond what is in the photo. Curator: Indeed. Considering the context in which the image was made deepens our understanding of the piece and its relevance today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.