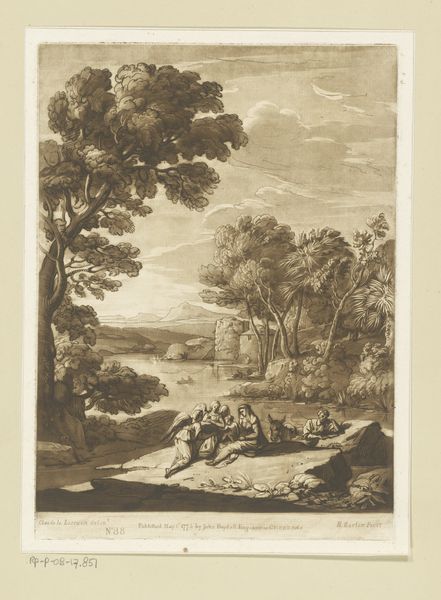

Dimensions: height 595 mm, width 436 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Pietro Antonio Martini created this engraving around 1772; it's titled "Saters en dryaden aan de oever van een rivier," which translates to "Satyrs and Dryads on the Bank of a River." Editor: The first impression is one of pastoral tranquility, a scene imbued with classical idealism, even a touch of melancholia, given its monochromatic palette and softened contrasts. The figures almost blend into the landscape, they are small within the grander scheme of nature. Curator: Indeed. The social context of the late 18th century, a time of growing urbanisation and industrialisation, informs such representations of an idealised, almost utopian natural world. This is how the wealthy envisioned their connection to the land and to the mythology around nature spirits. But notice the figures—not the robust peasants of earlier landscape traditions, but elegant, almost theatrical versions, echoing fashionable Rococo sensibilities adapted to a neo-classical style. Editor: And isn’t the presence of satyrs and dryads significant? Within a historical framework, these mythological figures allowed artists to navigate societal boundaries around nudity and sexuality. Are we seeing, perhaps, a sanitized representation of nature—where the "wild" has been safely contained and presented for consumption? Curator: Exactly. Their presence underscores the artwork's political dimension. How artists portray mythological beings often mirrors a society’s anxieties and aspirations. The very act of engraving, of creating a multiple, suggests accessibility—but who was this accessible to, and what message about societal norms around nature and leisure did it send? The imagery seems a far cry from feminist or postcolonial ideals of power. Editor: The tension is fascinating. What initially seemed a gentle landscape unveils deeper complexities—highlighting questions around the idealised vision of women, sexuality, and societal hierarchies subtly woven into the image. Curator: It serves as a visual document that offers insight into eighteenth-century socio-political ideals about humankind and our constructed relationship with the natural world. Editor: Agreed, there’s a lot more than initially meets the eye here. I’m already envisioning future scholarship opportunities based around your comments.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.