drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

#

french

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain

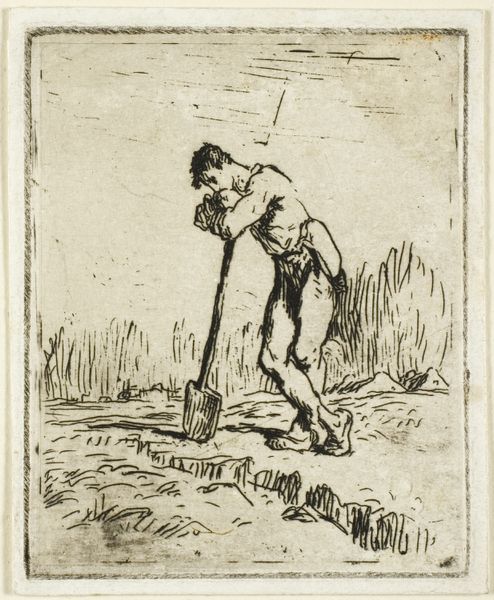

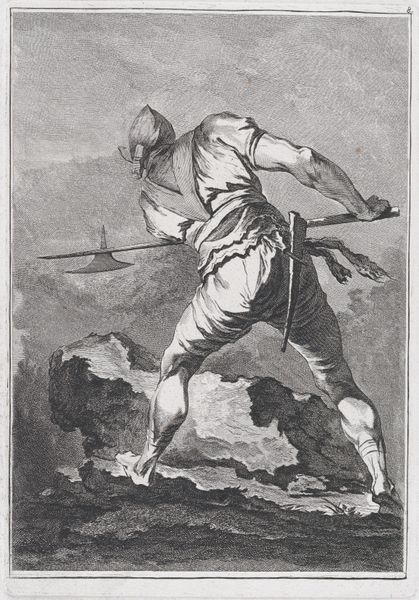

Editor: This drawing, “Le fendeur de bois” by Jean-François Millet, made with ink on paper, depicts a man splitting wood. There’s a powerful, almost brutal feel to it. What do you see in this piece, especially considering its social context? Curator: It’s a powerful image indeed, one that challenges the idealized view of rural life so common in earlier art. Millet, a key figure in the Realist movement, sought to depict the harsh realities of peasant labor, to show the dignity and struggle in work. Consider the Salon system; what messages about class and labour might this artwork have communicated to its contemporary audience? Editor: I guess showing the physical strain wouldn’t necessarily have been celebrated in academic circles back then. Curator: Exactly. Images like this were part of a broader movement challenging the established artistic and social hierarchies. By presenting the wood splitter with such gravity, Millet elevates the common worker, making a statement about the value of their contribution to society, and against artistic conventions of the time. Who had the power to commission art and whose lives were usually reflected? Editor: So it's a political act, in a way, to depict the working class with such honesty. I'd always considered Realism to be focused on capturing truth above all else, without thinking about the impact. Curator: Precisely. Realism, especially in Millet’s hands, became a tool to challenge prevailing power structures within the art world and wider society, broadening the range of acceptable subjects, of reflecting ordinary lives, within cultural institutions. It encouraged debate, demanded recognition, and prompted discussion about the dignity of labour in rapidly industrializing nations. Editor: That reframes the whole artwork for me. I was seeing a scene, but now I recognize it as a statement. Curator: And that's the power of art history: to help us understand not just what we see, but why it was created, who it served, and what it meant in its time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.